Peacekeepers from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) on patrol. (UN Photo/Marco Dormino)

The United Nations recently approved its budget for peacekeeping for 2018-19 as well as a slew of longer-term reform proposals. Just short of $6.7 billion has been committed thus far, with a further sum for the second half of the UN’s mission to Darfur (UNAMID) due in December and likely to take the final total to around $7 billion. This sum represents a roughly 7 percent cut on last year’s budget—although further payments to UNAMID may make the final cut closer to 3 percent.

The budget was negotiated over many weeks. In the end it was not approved until five days after the deadline, thereby briefly leaving the UN’s missions in a strange—and now retroactively authorized—accounting limbo. However, there is a real risk that the delicate compromise will buy time but no more, and leave unaddressed for another year fundamental tensions between different stakeholders visions of peacekeeping that threaten to bring peacekeeping to a standstill.

At the same time, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ reform proposals are likely to have a positive impact on peacekeeping, but are unlikely to result in a sea change in the way peacekeeping is conducted. The result is a precarious situation.

The budget passed by the Fifth Committee and the peacekeeping reform proposals illuminate the conceptual issues at hand in peacekeeping. Moreover, identifying these issues can help determine how the secretary-general’s new peace and security architecture might rise to the challenge.

The Budget and Peacekeeping Reform

UN peacekeeping continues to be eight times cheaper for the US than alternative approaches, yet the US government has pledged to cut peacekeeping by over $1 billion and continues to push for the closure of missions (read a more detailed look at the budget and cuts). The reality, however, is that very little can be safely cut, especially at smaller missions. Larger missions in the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Sudan also face grave difficulties as the peace the missions were established to keep disintegrates further.[1] The consequence was a comparatively small percentage cut compared to last year’s budget, but nevertheless one which could cause tensions and problems in certain missions.

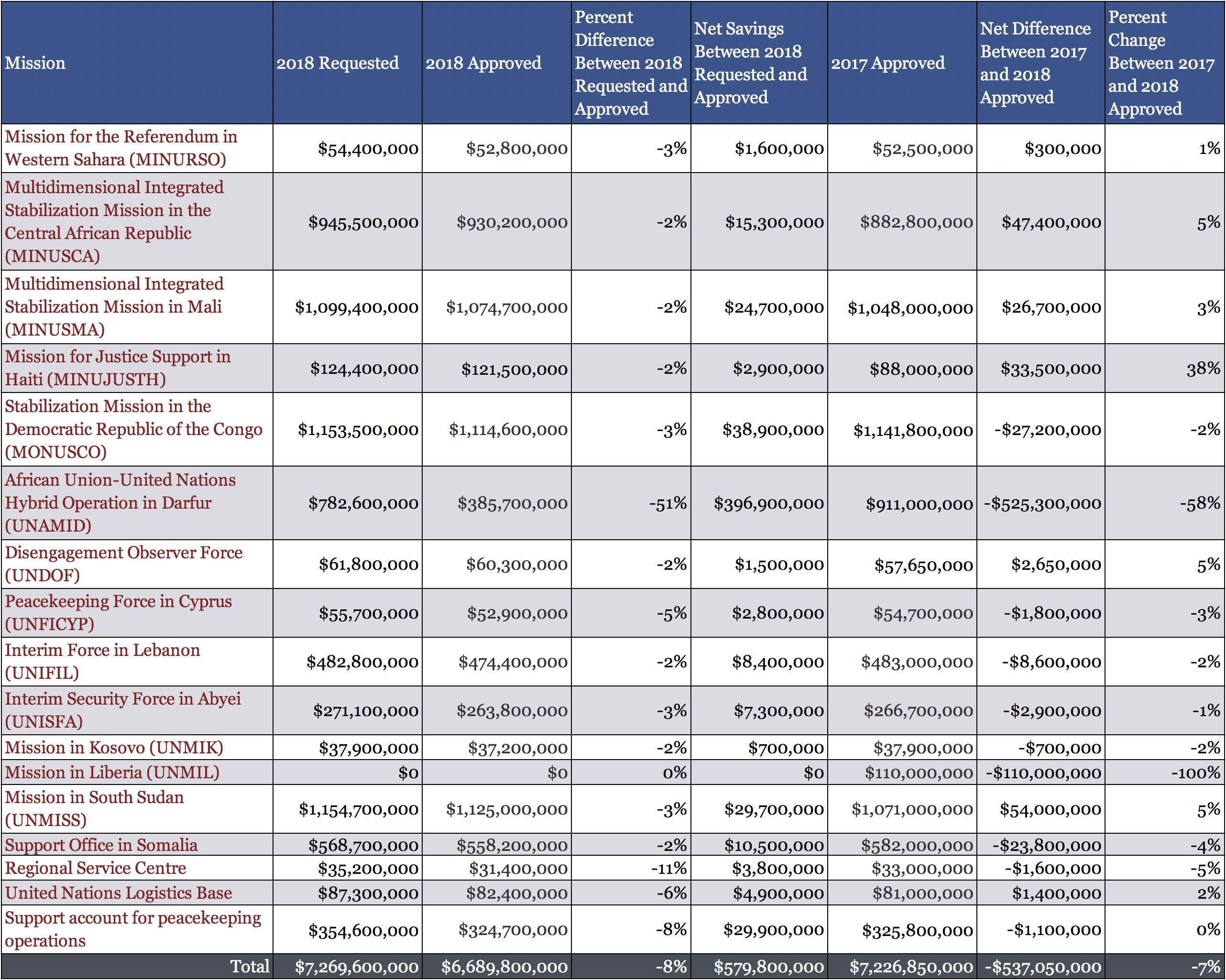

2017 and 2018 Peacekeeping Budget Comparison*

*Budget only covers the first six months, further funds will be approved in December and will alter these figures.

The financial circumstances are also a reflection of the nature of budgetary negotiations, which is frequently disconnected from the many other constituencies peacekeeping must answer to. UN peacekeeping was not the consequence of a holistic design process but rather emerged as the by-product of a series of improvisations, compromises, and evolutions, primarily in the 1950s.[2] As such it has multiple stakeholders and centers of influence.

The Security Council writes the mandates, and is often the greatest supporter creatively applying peacekeeping to perform multiple functions—including new and still ill-defined ones such as “stabilization” and, with some notable skeptics like China, “robustness.” The Fifth Committee of the General Assembly sets the budget and tends to have a more traditional view of peacekeeping based on consent, neutrality, and minimal force. Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs) provide the personnel, they wish to be consulted, to be valued (and paid) and to have their troops kept safe. Donor countries, mostly but not exclusively Security Council members, provide most of the money and want to minimize costs. The host nation wields an effective veto based on the fact that they provide at least a degree of consent to the mission, and they often seek to make the mission’s life as difficult as realpolitik will allow. Meanwhile the other non-state parties to the conflict are equally vital to the success of peace processes, but UN state centricity means they lack the leverage of the state actor. And then most importantly of all, but frequently least considered, are the views and needs of the “peacekept”: those living in the conflict affected area in whose name the mission exists.

We saw some of these dynamics play out in the budget debates. Russia allegedly pushed for cuts to the human rights budget, apparently as a negotiating ploy which could then be traded for other states backing off on cuts to the air operations budgets (Russian commercial contractors frequently being procured for these services). The impacts on the ground appear to have been a secondary consideration, although in the case of air operations perhaps a serendipitous one.

Performance suffers as a consequence of insufficient resourcing, and mediocre to poor performance is to the detriment of UN peacekeeping on the ground and as a brand. It is for this reason that the other half of the Fifth Committee’s debate, about long-term reform of UN peacekeeping, was of equal and perhaps greater importance.

Incrementalism

Given the tensions between peacekeeping’s different constituencies, it is small wonder that peacekeeping reform tends to be largely about the art of the possible: “reformettes”, in the wonderful phrase of one Francophone African diplomat. But even these tweaks have an incremental effect and add to the strain between what modern peacekeeping has become and what some constituencies still view it as.

Most substantive of recent “reformettes” was the 2015 High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) report which called for a greater emphasis to be placed on politics and for the end of the arbitrary distinction between political missions and peace missions. Secretary-General Guterres’ peace and security architecture reform, which was mostly approved during these same Fifth Committee negotiations, gives this a far greater chance of occurring.

Under this program the Department for Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and Department for Political Affairs (DPA) will be abolished and replaced by two new, and much more tightly integrated, departments: the Department for Peacebuilding and Political Affairs (DPPA) and the Department for Peace Operations (DPO). In a separate process, the UN Department for Field Support, which works very closely with DPKO on the logistics of peacekeeping, will be reorganized alongside the Department of Management (which currently has little to do with peacekeeping) to create a new Department of Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance, and a new Department of Operational Support.

Some contentious parts of the reform agenda were pushed back a year, e.g., the UN intended to create three regional administrative service centers in Nairobi, Budapest, and Mexico City. However, while many of the roles that would be relocated to these centers are based in New York, Uganda and the Group of 77 (G77) countries were concerned that the consequence would also be a downsizing of the UN Peacekeeping Regional Service Centre in Entebbe. For this reason no decision was taken.

HIPPO placed a strong emphasis on a people-centered approach in peace operations, particularly when it comes to the protection of civilians. This strand was largely missing in the secretary-general’s more recent reform proposal, “Action for Peacekeeping (A4P).” While this is unsurprising given that Action for Peacekeeping is a report largely focused on building high-level political buy in for peacekeeping, it does raise the concern that this vital aspect of peacekeeping reform could continue to be neglected.

HIPPO also emphasized partnership with regional organizations such as the African Union. This also doesn’t appear in Action for Peacekeeping, although it is clearly an issue the Security Council takes very seriously, even if thus far their support has been rhetorical rather than financial.

A4P reiterates most of the core HIPPO recommendations, however in its most radical departure strongly emphasizes “making peacekeeping missions stronger and safer,” taking its lead from the report of Lieutenant General Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz on UN peacekeeping fatalities, which recommends that the UN adopt a much more “robust” military posture.

What Does “Robust” Mean?

UN peacekeeping approaches are different depending on the context, and one of the frequently repeated criticisms of the dos Santos Cruz report is that it seeks to apply a model that may be well-suited to one particular context more broadly than conditions allow. Nevertheless, it might be constructive to discuss in the general case the logical consequences of a more robust or aggressive posture.

The traditional role of a UN peacekeeper has been that of de-escalation. By monitoring ceasefires, by acting as a buffer between armed groups, or by maintaining a basic standard of order, peacekeeping can carve out political space and help reduce tensions and allow armed groups on all sides to step down their activities. This hopefully has the long-term consequence of fostering more conducive circumstances for a sustainable peace.

“Robustly” using force to neutralize armed groups is very different and does not have this effect. This is not a strategy for de-escalation and can in many circumstances escalate and exacerbate conflict. And this is the case even for the robust use of force in the interest of protecting civilians.

There will often be, however, compelling reasons for a robust approach—preventing atrocities for example—and the path to an equitable and thus sustainable and lasting peace is not always a flat downward slope. But it needs to be recognized that such actions can potentially run counter to the objective of reducing the intensity of conflict. Serious strategic thought therefore needs to be given to what a robust approach can mean for conflict prevention and the prospects of peace in the long term—is it possible to shoot your way to peace?

That is not a question with a simple answer, but part of an approach to answering it could come from better staging and phasing of a mission. In certain phases intensification is required for reasons of protection, and then at a given – not always easily identified – moment, there needs to be a pivot to de-escalation in the interests of long term peace and stability. In other words: at times atrocity prevention and harm reduction will trump peacebuilding and conflict prevention and at times there will be opportunities to deescalate. Ideally, expectations should be managed accordingly and clearly communicated so that there is a more developed understanding of what the mission is trying to achieve and what the likely short and long-term outcomes are. This makes communication with local communities even more vital, which requires funds to be spent on civilian personnel and travel—areas which have been systemically cut in recent years.

The UN Brand

In an ideal world a robust strategy would be paired with a division of responsibilities, as between the UN and AU in Somalia, UN and G5 in Mali, or UN and UK in Sierra Leone, whereby the UN would provide the de-escalation mechanism of peacekeeping, and a separate—ideally allied, ideally regional—force would provide robust interventions when required. Such an arrangement may be more appropriate in terms of leveraging these skillsets and could also serve to protect the reputation of UN peacekeeping. The UN peacekeeping “brand” continues to suggest a certain approach: neutral, a non-party to the conflict, and using only minimal force.

However, there will always be cases where the UN is the only available or trusted force, and thus may be asked to step into a role beyond that of traditional peacekeeping. The question then becomes: what should the UN do under such circumstances?

It might be that using a different term for this more robust kind of intervention is helpful in protecting the integrity of the UN peacekeeping “brand.” Sadly, such clarity might not be possible and there might continue to be a need for ambiguity in order to maintain host nation consent. The gap between the tasks the Security Council wishes the mission to perform, and the tasks that many host nations are comfortable with the mission performing, has been growing for some time. Nevertheless, UN peacekeeping missions have skillfully operated in the margins and grey areas of memorandums of understanding to perform a significant amount of useful work. If missions were explicit about the fact that what they were doing was in some cases not so much peacekeeping as an implementation of the responsibility to protect, they might find that host nation consent is withdrawn.

Distinguishing Between Necessity and Virtue

A4P will very soon be endorsed by a short “Declaration of Shared Commitments” by member states. They will unveil this during the first week of the UN General Assembly next week. The purpose of the declaration is to get the largest number of states to pledge their political support for peacekeeping, the language of the declaration does not challenge or significantly alter our understanding of the term.

Peacekeeping policy continues to be dominated by the art of the possible, much as peacekeeping budgets continue to be a negotiation entirely satisfying to none of the parties involved. This is not a landscape which lends itself to sweeping changes or big bold new ideas but to “reformettes” and to creativity in the margins of mandates and conceptual understandings. This has been true of UN peacekeeping since the very beginning. Frustrating and ambiguous as this may be, it has not stopped peacekeeping efforts from saving many lives, helping to avert many crises, and working to sustain peace.

But while we have to accept the frustration and ambiguity, we don’t have to like it. There is an important role for civil society in doing what the UN cannot and member states will not, and clarifying the impacts of insufficient resourcing, the consequences of a more robust mission posture, and the need to reflect the needs and wishes of the “peacekept.” Even if, as seems likely, the UN still has little choice but to make do as best it can, increased pressure to clarify these impacts will at least allow for the UN to negotiate more effectively for suitable resources and reasonable expectations.

Fred Carver is the Head of Policy for the United Nations Association-UK, and has a particular focus on UNA’s work on UN peacekeepers.

[1] These remarks were made during Martin’s keynote address to the conference UNA-UK jointly convened with the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in May.

[2] For more information on this process see Chapter X in A Life In Peace And War by Brian Urquhart.