French soldiers with MISLOG-BANGUI, a logistic mission deployed to provide support to the European Union training mission and to French troops with the United Nations mission (MINUSCA), conduct a patrol at their base in camp M'Poko, Bangui, Central African Republic, on September 13, 2022. (BARBARA DEBOUT/AFP via Getty Images)

In a 2015 report, then-Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon remarked that the United Nations (UN) had “entered an era of partnership peacekeeping.” And, indeed, in the past three decades, the UN has frequently and in various modes of cooperation conducted peacekeeping in partnership with regional organizations, ad-hoc coalitions of states, and even single member states. Despite many challenges inherent in this inter-organizational cooperation, we find in our research that parallel deployments of UN and partner missions are effective in curbing battle violence—more effective than peacekeeping by any actor alone. This raises important questions about the role the UN will play in the global partnership for peacekeeping in the near future.

There is a lot of ambiguity surrounding the term “partnership peacekeeping.” Even if not used as a lofty euphemism for “letting regions deal with their own conflicts,” the term encompasses at least three very different cooperation arrangements: parallel deployment of a UN and a non-UN mission, sequential deployment in which a non-UN mission hands over to the UN or vice versa, and support packages in which the UN merely assists a non-UN mission financially or with logistics. In our study, we are primarily concerned with parallel deployments of UN and non-UN missions in the same conflict. Even these parallel operations take on many shapes. Common to most of them is that the non-UN partner is primarily composed of troops and reinforces the military side of the crisis response.

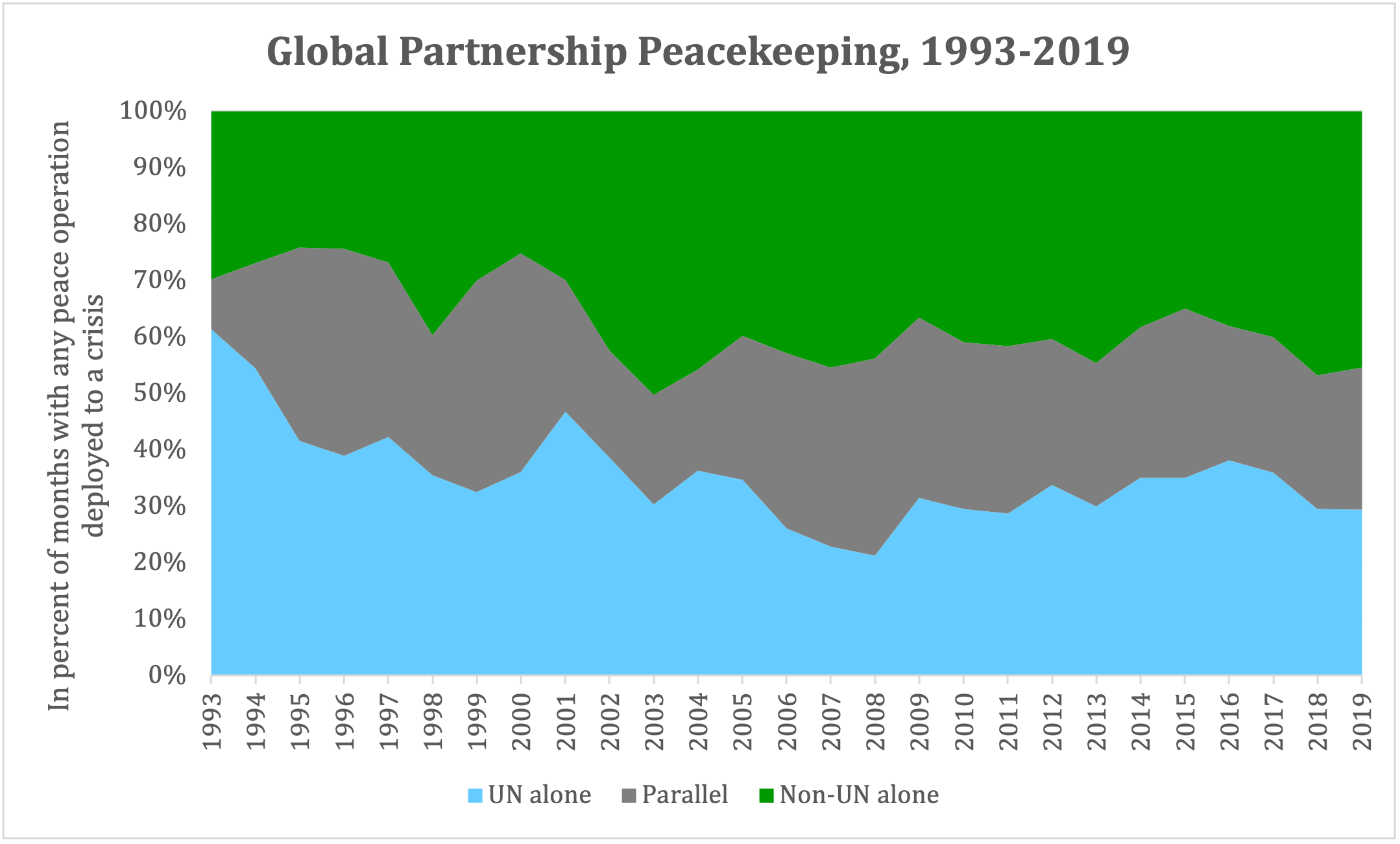

Source: Bara & Hultman 2020

This kind of parallel peacekeeping is fairly common. In around 44 percent of instances (deployment months) during which a UN mission was present in an intra-state conflict between 1993 and 2019, there was a non-UN partner present at the same time. Remarkably, parallel deployments have not become more frequent over time, as the graph below shows. If we are indeed in a new era of partnership peacekeeping, it is conversely characterized by more regional organizations and ad-hoc coalitions deploying alone, without a UN partner. This is not surprising, given that the UN has authorized no new military peacekeeping operation since 2014. The new era may also be characterized by an increasing number of peacekeeping actors that respond to the same crisis. In Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR), where two of the UN’s remaining “big four” missions are (pending MINUSMA’s exit later this year), seven different organizations had or have peace operations: the UN, European Union, and French operations in both, plus the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the G5 Sahel in Mali, and the African Union and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) in the Central African Republic.

Given this variety of very different peacekeeping actors, it is not surprising that analysts have predominantly focused on highlighting the challenges that emerge from parallel deployments. These include diverging mission objectives, competition around certain tasks, restrictions on intelligence sharing, lack of trust in partners’ military capacities, varying levels of UN Security Council oversight over missions, and negative repercussions of one mission’s actions on other missions. This last point is particularly critical for the UN: Violent counterinsurgency and counterterrorism activities by non-UN partners can pose a risk to UN staff on the ground if the local population is not able to distinguish who is who. If civilians die in these operations, locals may accumulate grievances against all international forces present.

It is therefore imperative to ask whether the benefits of parallel peacekeeping outweigh the risks. Our recent study suggests they do. In a statistical analysis of monthly data on UN and non-UN peacekeeping troop size in Africa between 1993 and 2018, we estimate the effect of solo and partnership peacekeeping operations on the number of combatants and civilian fatalities on the battlefield. We find that parallel peacekeeping is more effective than no peacekeeping, and more effective than peacekeeping by the UN or another organization alone in bringing down battle violence. This is of course a narrow standard of peacekeeping success. However, given the militarized nature of most partner forces, it aligns with the aspirations and potential outcomes of many parallel deployments: stabilization.

We find that UN troops decrease battle violence also when they deploy alone, which is what a large body of research had already established. However, the UN mitigates this violence more effectively and with fewer blue helmets when supported by a non-UN mission—the larger the better. This partnership benefit, moreover, does not appear to be driven by the fact that there are more boots on the ground with two missions rather than one. Importantly, we find no evidence that non-UN missions alone are generally associated with violence reduction. A UN partner changes this: Only with a sizable UN mission in parallel, missions led by regional organizations or ad-hoc coalitions of states effectively bring down battle violence. We believe this is because the UN’s more multidimensional engagement is needed to offset the potential negative effects of an all-too-militarized approach to violence reduction. To critics of counterinsurgency, this will not come as a surprise.

We believe the effectiveness of partnership peacekeeping is intrinsically linked to mission complementarity. UN and non-UN missions use different strategies and work via different mechanisms, and these mechanisms can reinforce each other in parallel deployments. In an ideal division of labor, military force applied mostly by non-UN troops, and which the UN is not permitted or equipped to employ, works in tandem with UN peacekeepers’ broad toolbox. UN peacekeepers do not only regulate behavior of belligerents through deterrence but also by building institutions, providing aid and development, and engaging in mediation. In contrast, non-UN missions usually deploy soldiers that actively engage belligerents in combat. Both deployed together may help to convince combatants to stop killing each other. The UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), for instance, deployed in 2014 after the French operation Sangaris was authorized by the UN Security Council to counter the raging violence in the Central African Republic (CAR). For two years, Sangaris forces and UN blue helmets were deployed in parallel. Mission reports show that Sangaris forces actively fought rebels, sometimes with operational or intelligence support of UN troops, while the UN patrolled buffer zones, protected humanitarian convoys, mediated low-level disputes, and arrested war criminals to provide security. During this time of partnership peacekeeping, levels of battlefield violence decreased significantly.

Now, as is always the case with comparative analyses of a large number of cases, our findings do not imply that UN and partner missions always complement each other, or that this division of labor is effective in every context. In addition, it is important to emphasize that our findings only pertain to combatant and collateral civilian fatalities. We do not study the effect of partnership peacekeeping on other forms of violence, conflict termination, or sustainable peace. Furthermore, our study design is not suitable to compare different partnership peacekeeping arrangements over time. We cannot make any inferences on the effectiveness of particular arrangements common in the most recent time, such as the multi-actor engagements in Mali or CAR, compared to older conflicts where only the UN and one other actor were involved. But we can infer with considerable certainty that when assessed across all the missions studied and compared to scenarios without parallel peacekeeping (or no peacekeeping at all), partnership peacekeeping is linked to fewer deaths on the battlefield.

This raises a critical question: what role will the UN be able to play in the global partnership for peacekeeping going forward? Since Ban Ki-moon evoked the new era of partnership peacekeeping in 2015, the UN has not deployed a single new military peacekeeping operation. Given the current geopolitical dynamics and illiberal pressures on UN peacekeeping, this is unlikely to change in the near future. Is the model of parallel peacekeeping by UN and non-UN missions a model on the way out? Or are we entering a new “New Era” in which partnership peacekeeping will inevitably mean outsourcing peacekeeping to partners? The New Agenda for Peace (NA4P), the UN Secretary-General’s policy brief released this summer, certainly points in that direction, as Crisis Group colleague Richard Gowan notes: The New Agenda talks little about what the UN itself can do as peacekeeper, but what regional and subregional organizations and member states should do themselves, with the UN in a mere supporting role.

Our findings do not suggest that this will be enough. UN blue helmets are not just a partner in peacekeeping, but, according to our results, the crucial partner, and key in reducing violence in civil wars. In other words, the UN’s multidimensional approach to peace support cannot simply be replaced by putting more (non-UN) boots on the ground. The type of robust stabilization and counterterrorism operations that the NA4P calls for, led by African partners to deal with a proliferation of unruly armed groups on the continent, may be needed, but may not work unless they are part of a broader political strategy and multidimensional approach to peace support, which the UN typically stands for.

But of course, wishful thinking does not help given the geopolitical realities in the UN Security Council. Instead, the discussion should move to how non-UN organizations can themselves provide the complementary capacities that seem to be the driving force behind the beneficial effects of parallel peacekeeping. Supporting non-UN missions in expanding their toolbox of non-military peacekeeping measures is one way forward, as has been suggested elsewhere. Building on the already existing comparative strengths of different organizations to provide a multi-actor multidimensional response is the other. The EU and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in particular have police and civilian peacekeeping expertise and experience that can be leveraged in conjunction with more forceful military missions. One role for the UN could be to coordinate such a multi-actor response or perhaps even accompany it with a UN political mission.

Corinne Bara is a Senior Researcher at ETH Zurich’s Centre for Security Studies. Maurice P. Schumann is a PhD Candidate at the Hertie School in Berlin.