When former Syrian president Hafez al-Assad ordered the siege of the city of Hama in 1982, the world was not watching. Between 10,000 and 40,000 people were killed over the course of 27 days under Bashar’s father’s reign—the variance in the estimates are a testament to how little documentation there was of the massacre.

The death toll in today’s civil war in Syria recently surpassed 100,000, and between mid-January and mid-May of 2013 alone, UN investigators identified 17 incidents that could be defined as massacres.

The public can no longer claim ignorance when mass atrocities take place. From handheld cameras in Aleppo to powerful transnational civil society movements seeking to “Save Darfur,” in the twenty-first century, information and even early warnings about mass atrocities abound. So why have responses from governments—actions to prevent or end these atrocities—failed to catch up?

Analysis

The war in Syria may be the most well-documented war of all time. Syrian citizens have been reporting prolifically on the conflict in their country via YouTube videos and over Skype. Outsiders have even created new kinds of single-issue websites to document the war as it happens. “War crimes and crimes against humanity have become a daily reality in Syria,” UN investigators concluded in their last report, “the harrowing accounts of victims have seared themselves on our conscience.”

Inside Syria, the war over information—and the power it holds—continues in parallel to the violence. The Syrian army allegedly cut off communications before besieging cities like Banias and Bayda, but harrowing videos soon emerged nonetheless, showing evidence of massacres of men, women, and children. In fact, the Syrian government may still be able to turn off access across the entire country—in early May, another blackout left much of the country without Internet or phone service for two days. Web security firms and others said the government was almost certainly responsible, though Syrian authorities denied this.

Yet, with brutal crimes being committed by all sides, it would not be in the government’s long-term interest to keep communication lines down. Indeed, as extremist forces gain the upper hand among the opposition groups, risking even more civilian casualties, the Syrian president has been stepping up his own propaganda campaign: he recently added an Instagram account to his various social media tools, sharing high quality images of him and his wife greeting supporters and assisting the needy.

While documentation becomes more sophisticated, international instruments for responding to the violence and preventing further atrocities are lagging behind, even with the advent of the UN-endorsed concept of a “responsibility to protect.” One year ago, the UN Secretary-General laid out tools in a report on the responsibility to protect. They include fact-finding missions and commissions of inquiry, monitoring and observer missions, public advocacy, mediation and preventive diplomacy, sanctions, and coercive military force. Yet, despite efforts to put these tools to use—with the significant exception of coercive military force—international actors are still grasping at straws in Syria.

Expanding persuasive powers—through political missions, preventive deployments, and in Syria’s case the Geneva II peace talks—is an important part of this picture. But new research from the International Peace Institute (which hosts this website) on responding to genocide, mass violence, and mass atrocities shows that it is the even more elusive instrument of political will that remains so vital to bringing such responses to life and seeing them succeed.

In general, governments, if not always the public, have known about mass violence and mass atrocities. When the UN Security Council had information on what was happening during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, little was done to stop it. According to General Romeo Dallaire, then head of the UN peacekeeping mission there, the Council members were well informed, but chose not to act anyway. National interests prevailed. In addition, particularly in the early stages of the genocide, there was little pressure from Council members’ domestic constituencies to take action.

Ultimately, it was the genocide in Rwanda that created the impetus for the normative shift towards a responsibility to protect, under which governments have acknowledged their duty to protect civilians in other sovereign states when necessary. Nearly two and a half years into the conflict in Syria, the prevalence of media coverage of the conflict combined with the glaring lack of effective response makes governments’ failures to act all the more problematic.

Yet, answers are not forthcoming. Military intervention remains unadvisable in Syria, not least because of the significant regionalization of the conflict. Instead, a newly revitalized political push is needed for key international actors, in particular the United States and Russia, to come together and commit to collective action to de-escalate the conflict and bring the parties to the negotiating table. But it remains unclear who among the opposition should be at the table, and how the many crimes of Bashar al-Assad and others can be dealt with alongside a political deal.

In the IPI volume, editors Adam Lupel and Ernesto Verdeja analyze the key ingredients for generating the political will to keep tackling these difficult questions and pushing for a solution. Among other factors, they emphasize the importance of identifying common interests among states. In the case of Syria, this might mean helping the US and Russia to see that stemming the refugee flows out of Syria, taming the growing regional instability, and preventing further damage to Middle Eastern economies is in their own national and collective interests. Lupel and Verdeja also point to the need for visionary leadership, which we have yet to see from either Barack Obama or Vladimir Putin.

Ultimately, the tools used to get the message out of Syria can be employed on the “response” as well as the “warning” continuum. If information holds power, creative public advocacy could be used to leverage the flow of information to foment and sustain political will to slow and ultimately end the violence. Meanwhile, within Syria, civilians will continue to draw on the variety of information and communication technologies to stay informed, devise their own methods for managing the violence at the local level, and get out of harm’s way.

Marie O’Reilly is Associate Editor at the International Peace Institute. She tweets at Marie_O_R.

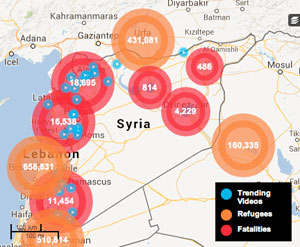

About the photo: Screenshot from a map on syriadeeply.org detailing fatalities, refugees, and trending videos.