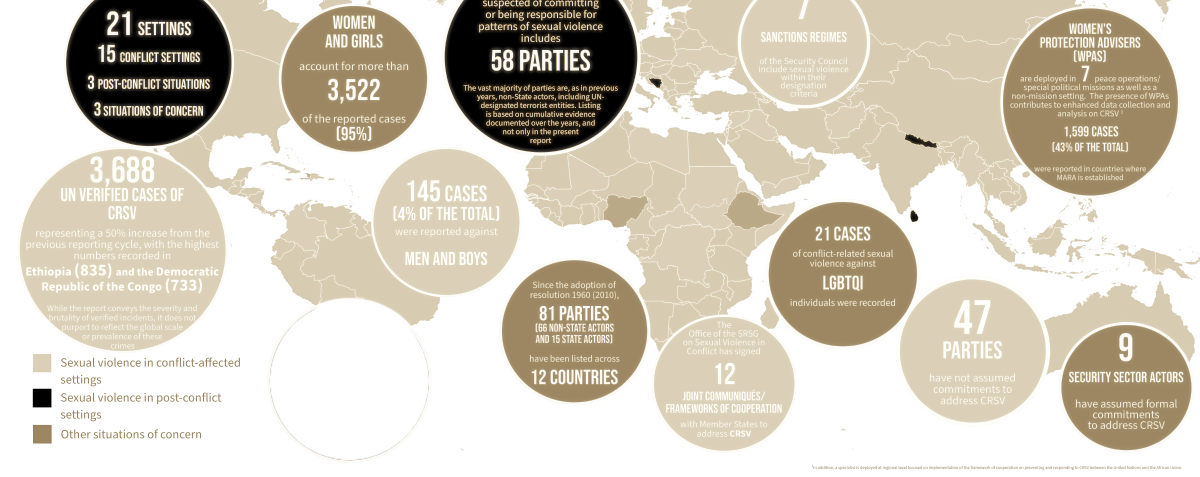

Part of the factsheet from the 2023 Report of the Secretary-General on CRSV.

Since the Security Council first recognized conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) as a threat to international peace and security in 2008, the United Nations (UN) has developed an increasing number of pathways to prevent and respond to such crimes. One of these pathways is the annual report of the Secretary-General on CRSV, which includes an annexed list of perpetrators who are credibly suspected of committing or being responsible for patterns of CRSV violations in contexts on the agenda of the Security Council. This list can be a tool to publicly name perpetrators and to open a door for engagement that may facilitate changes in behavior.

The second tool is UN sanctions. Some sanctions regimes have designation criterion that allows for perpetrators of sexual- and gender-based violence (SGBV) to be sanctioned for committing these violations. (Whereas the Secretary-General reports on patterns of CRSV, sanctions regimes use the broader term “SGBV.”)

Over the past two decades, the UN Security Council and Secretariat have attempted to increase the links between the CRSV agenda and sanctions regimes. The Secretary-General has also consistently recommended increasing the links between the annual reports and sanctions. Based on our research, we found that overlap between the two remains limited, and there are opportunities to enhance their complementarity. We also found constraints on the panels of experts collecting evidence on SGBV cases as mandated by the UN Security Council, in addition to political barriers within sanctions committees.

For our analysis, we focused on two aspects: (1) understanding the level of coherence between the parties listed in the annex of the annual report and sanctions and (2) analyzing how sanctions have been used in response to SGBV. To make this determination, we looked at overlap in two ways: first, whether parties who appear in the annex are also designated for sanctions, and second, whether the party is specifically sanctioned for committing SGBV (as opposed to a different violation under the regime).

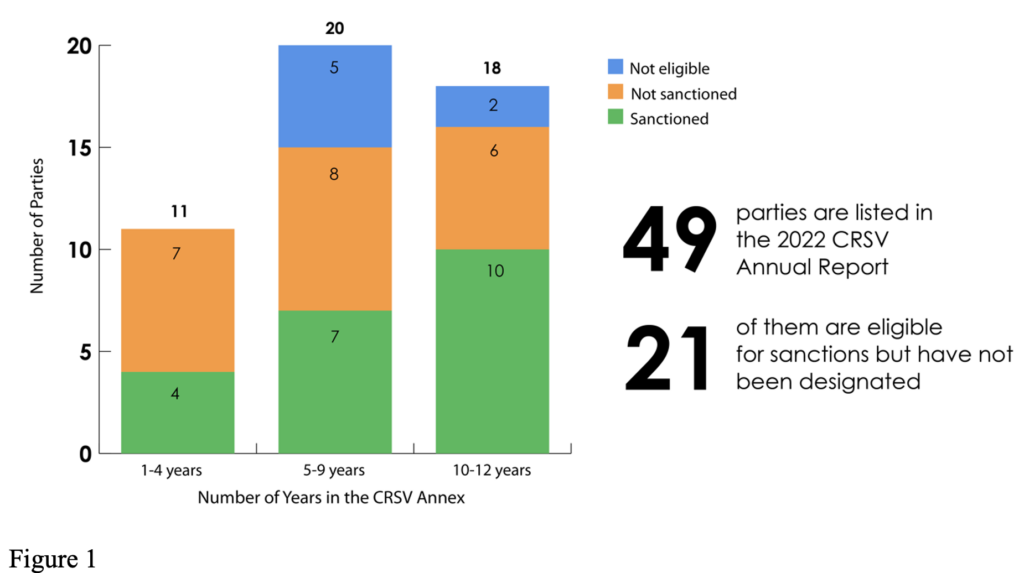

We based our research on the 2023 Secretary-General’s report released last summer which covers the 2022 reporting period. In that report, 49 parties—both state and non-state groups—were listed in the annex because they committed or were responsible for patterns of CRSV violations.

One major finding is that many parties listed in the annual reports of the Secretary-General are not sanctioned, even in contexts where sanctions regimes are in place (see Figure 1). Of those who are sanctioned, the majority are sanctioned for reasons other than SGBV.

One major finding is that many parties listed in the annual reports of the Secretary-General are not sanctioned, even in contexts where sanctions regimes are in place (see Figure 1). Of those who are sanctioned, the majority are sanctioned for reasons other than SGBV.

Overall, designations for SGBV violations are rare. Of the 614 individuals and 138 entities sanctioned, only 25 individuals and 2 entities are designated for committing SGBV. Thus, despite the fact that sexual violence is known to be widespread across many of the contexts where a sanctions regime is in place, designations for committing SGBV account for less than 4% of the 752 currently sanctioned by the UN.

Why Are So Few Parties Designated for SGBV?

In seeking to understand the reasons for these phenomena, we find that constraints in investigating and reporting by the panels of experts and political barriers within sanctions committees are the primary causes.

Panels of experts are tasked by the UN Security Council with building detailed “statements of case” on suspected perpetrators, in which each documented violation is corroborated by a minimum of three carefully vetted witnesses or sources. Gathering this level of evidence can be quite difficult given security constraints, intentional blockages by state and non-state groups, and difficulty accessing remote areas. Even in cases where witnesses can be accessed, they may be reluctant to participate due to shame or lack of trust.

Experts also work with very few resources; they are given modest salaries under difficult working conditions and no additional resources, which might be necessary if witnesses need access to transportation, translation, or other services to facilitate interviews and investigation processes. This was cited as a major impediment to the work of the experts.

Experts also work with constrained capacity, as humanitarian and human rights–related crimes are usually covered by a single expert. Thus, even for a country like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which has a massive number of armed groups and huge territory, there is only one expert to investigate all SGBV and humanitarian violations for the entire country, making reporting extremely difficult.

Despite these stumbling blocks, political challenges are arguably the greater barrier to designations for SGBV. Because sanctions committees operate on the basis of consensus, the extent to which designations are adopted depends on the political and working relationships of committee members and the extent to which they hold a common vision on the role of sanctions for a given context. Thus, in some contexts like Haiti or the DRC, there has been stronger consensus on the use of sanctions, including for SGBV. However, in other contexts, this has been more difficult. For example, in Sudan, only three individuals are currently sanctioned (none for SGBV), and there have been no new designations since 2014 despite historically high levels of violence in Darfur and across the country.

The lack of designations for SGBV is particularly pronounced in the case of terrorist organizations. Even though terrorist organizations have few (if any) sympathizers within the Council, there is a noticeable lack of designations for SGBV for these organizations. In particular, the 1267 sanctions regime, which covers ISIS, Al-Qaida, and associated groups, contains no designation criteria for any humanitarian or human rights violations, including SGBV, despite some of the worst atrocities on record. Even in counterterrorism environments where SGBV criteria do exist, they have been underutilized. For example, SGBV was added to the regime for al-Shabaab in 2018, yet no individuals are currently sanctioned under this criterion despite the fact that al-Shabaab is a persistent perpetrator within the annual reports of the Secretary-General, listed for the past 9 years.

Elevating SGBV within UN Sanctions Regimes

The lack of designations for SGBV, including for persistent perpetrators listed by the Secretary-General, illustrates that these crimes are not always elevated to the same extent as other violations within UN sanctions regimes. Moving forward, there are ways for member states to elevate SGBV crimes and improve the connection between sanctions and the Secretary-General’s reports.

First, member states can explicitly list SGBV as a designation criterion in all sanctions regimes where sexual violence may be taking place. For example, member states can add SGBV criterion to the 1267 regime so that actors within ISIS, Al-Qaida, and associated elements can be sanctioned for these violations. Related to this, member states can make more use of the SGBV criterion when it is available, including for example, in the sanctions regime for al-Shabaab.

Member states can also increase the overlap between parties listed by the Secretary-General and sanctions regimes. Currently, there is no formal mechanism that ensures that sanctions committees review the Secretary-General’s reports. Creating a formal mechanism would ensure that sanctions committees review the listed parties and consider designating them for sanctions.

Finally, member states can provide additional resources for the panels of experts. Panels should be given the resources needed to fulfill their mandates, including translation and other basic services. Member states can also recruit more experts who specialize in SGBV to serve on panels rather than having one individual responsible for all human rights and humanitarian law violations.

Despite the strides taken by member states and the UN over the past fifteen years to prevent and respond to SGBV, more work needs to be done. There are concrete ways to elevate SGBV within UN sanctions regimes and increase the link with the Secretary-General’s reports. However, these measures require member states to overcome political barriers and commit to preventing and responding to SGBV.

Jenna Russo is the Director of Research at the International Peace Institute and the Head of the Brian Urquhart Center for Peace Operations

Lauren McGowan is a Policy Analyst at the International Peace Institute.

This article is based on the authors’ report “UN Tools for Addressing Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: An Analysis of Listings and Sanctions Processes.”