A Bolivian indigenous farmer jumps the irrigation waters of his crops from the contaminated Choqueyapu river in Rio Abajo, south of La Paz, Bolivia on Friday, March 17, 2006. (AP Photo/Dado Galdieri)

The climate crisis and its compounding impacts will greatly influence how we shape our common future. But the ways in which we perceive, understand, and respond to climate impacts are modulated in complex ways by culture and heritage. Understanding what people value and prioritize in their own cultural contexts can be a powerful factor in designing and implementing effective strategies to rein in harmful heat-trapping emissions and help communities adapt to unavoidable impacts.

A new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, published in the lead-up to COP27 and co-authored with UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and ICOMOS (the International Council on Monuments and Sites) has highlighted, for the first time in the science panel’s history, the vital importance of protecting cultural heritage in addressing climate change.

Heritage consists not just of tangible assets such as buildings, monuments, archaeological sites, art, and museums, but also of intangible heritage. This heritage, passed down and developed through generations—over decades to millennia—can include practices, food traditions, languages, skills, ceremonies, artistic expression, cosmologies, identities, and ways of knowing. Such intangible heritage often resides in communities that have historically been marginalized, discriminated against, or actively persecuted—and are also often the most vulnerable to climate change.

Decades of scant attention on cultural heritage has resulted in a global imbalance in fully understanding the impacts of climate change. The IPCC found that the lack of a comprehensive and balanced understanding of cultural heritage in climate risk assessments has been exacerbated by an over-representation of built heritage and well-known sites in climate and heritage policy discussions. Losses and damages caused by climate change to intangible cultural heritage, such as Indigenous and local knowledge and traditional agricultural practices, have been vastly underestimated.

Much of this threatened and vulnerable intangible heritage offers opportunities for learning from climate adaptation practices in the past and increasing resilience in the future. For example, pastoral systems used by nomadic people in Africa, who follow or herd their livestock to suitable open grazing land, developed as effective responses to the natural aridification of much of the continent thousands of years ago. Ancient water access and management practices also have a great deal to contribute today. Complex irrigation systems such as the acequia of Spain and New Mexico, the aflaj of Oman, and those in Peru’s Nor Yauyos Cochos preserve and Honghe Hani rice terraces in China’s Yunnan province have enabled dryland and mountain agriculture for centuries to millennia. In Nepal, the system of underground piped water and public fountains (hiti), originating in the 6th century, are essential in providing access to water for a large proportion of the population of the Kathmandu Valley, but have been increasingly going into disuse.

The IPCC report centers the importance of acknowledging different ways of knowing and the diverse knowledge systems at play for understanding, measuring, monitoring, and recording. Seasonal phenomena, for example, are important for triggering or celebrating agricultural, fishing, and hunting activities in many Indigenous peoples’ annual calendars, often accompanied by ceremonies. In Oregon, the Siletz people use the emergence of eel ants (flying termites) and other environmental signals to trigger their Pacific lamprey harvest and simultaneously the traditional eel dance. With changes in the climate come changes in seasons, phenology (seasonal biological changes directly linked to climatic conditions), disconnection of historically-related ecological phenomena, and alterations in species distribution. For Native Alaskan Iñupiat, bowhead whale-hunting and the spring whaling festival have been integral to community identity for thousands of years, but climate changes to the Arctic marine environment are threatening that.

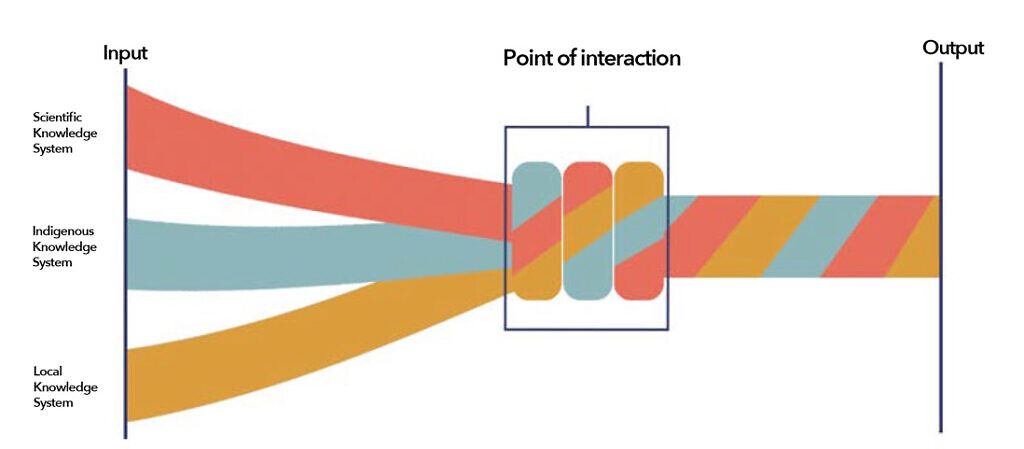

Often Indigenous and local communities are the first to notice changes in ecological phenomena as their detailed traditional knowledge of local species interactions and weather has been built over many generations of observation and cultural interaction. According to the report, the three primary types of knowledge—scientific, Indigenous, and local—should not be merged into a single hybrid system, but should be used alongside one another in a “braided” system of knowledge to gain the full benefit of the different systems and perspectives.

Efforts toward absorbing and integrating Indigenous knowledge into science-based climate impact and adaptation strategies have too often taken place without the full participation of the knowledge holders themselves. The same is true at the decision-making and political levels, where Indigenous and local communities have not had the platform to speak for themselves, rather than having their voices mediated through others. More often than not, they have not been provided access to decision-making and climate action planning, and adaptation plans are the poorer for it—missing key knowledge, insights, and practice toolkits. Traditional knowledge has also been cherry-picked or appropriated, which the IPCC report makes clear in stating that:

“When in pursuit of collaborative research/work between knowledge systems it is critical to be clear on data-sharing and benefit-sharing agreements so that [Intellectual Property Rights] are maintained, consent is transparent and groups (e.g. Indigenous people and local communities) are not disadvantaged in any way by giving or having their knowledge used, misused or abused.”

There are a growing number of examples of successful climate resilience projects where solutions have been co-created and are being jointly implemented by management agencies and Indigenous and local communities. In the Kakadu National Park World Heritage site in Australia’s Northern Territory, Aboriginal co-researchers and Indigenous rangers are working with the national science agency (CSIRO), the park management board, and other partners to improve decision-making for the management of important species on Indigenous lands in a changing climate.

In California, efforts are underway with scientists and traditional knowledge holders to understand how Indigenous heritage developed over centuries in the management of oak forests, including sacred groves, as traditional practices such as acorn collection and processing can underpin adaptive fire management strategies and resilience to drought in a rapidly changing climate.

Given what we now know about its role, more attention should be given to the loss and damage (L&D) of intangible cultural heritage at COP27 and beyond. Until now, because it cannot easily or effectively be given an economic value, cultural loss and damage has been largely overlooked in political L&D discussions, which have overwhelmingly been centered on calls for direct climate financing to be provided by richer nations such as the United States and Western European countries that have been historically responsible for most carbon emissions.

Climate finance to help low-income countries in the Global South respond to worsening climatic conditions is critical. An analysis by the Heinrich Böll Foundation suggests that richer nations should develop mechanisms to contribute $150 billion to offset L&D in the Global South by 2030. Even this is a drop in the bucket. By 2050, the Böll Foundation analysis estimates losses and damages from climate change will reach at least $1 trillion-$1.8 trillion, and this is without putting any kind of value on the massive worldwide degradation to cultural heritage of all types.

The new IPCC/UNESCO/ICOMOS report has highlighted the potential harm caused, especially to Indigenous people and historically marginalized communities, by underestimating climate impacts on cultural heritage and undervaluing non-scientific knowledge systems.

It also demonstrates the resilience benefits that could be gained from redressing the balance. Rather than charting an entirely new path, learning from traditional knowledge holders and embracing traditional resilience practices can strengthen climate adaptation and mitigation efforts. A beginning step is to create a new climate science research agenda for cultural heritage which centers Indigenous and local knowledge and resilience strategies based on traditional practices.

We also urgently need to initiate discussions on the true costs of loss and damage. Nations responsible for the majority of historic global emissions have an opportunity to commit to providing adequate L&D financing, and all countries can move toward providing equal weight and attention to non-economic L&D, including intangible cultural heritage.

A version of this article was originally published by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). Adam Markham is Acting Director of the Climate and Energy Program at UCS.