The Interoceanic Highway, shown here, allowed loggers, ranchers and miners to generate hundreds of miles of illegal and informal offshoots that brought additional deforestation and environmental harm. (David Salisbury)

The Amazon rainforest is overrun with informal and illegal roads, a process accelerated by a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, a lack of governmental oversight and enforcement, and the policies of Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, who faces a close runoff election on October 30. Three Amazonian departments in Peru saw road expansion increase by 25% from 2019 to 2020 and 16% from 2020 to 2021. In the Brazilian Amazon, roads are being built at such a rapid pace that researchers are turning to artificial intelligence to map the expansion.

Roads are the most damaging infrastructure in the tropical rainforest, bringing deforestation and a host of related cultural and environmental impacts. When the pandemic forced governments to reduce monitoring and law enforcement in the remote rainforests, the illegal road builders, loggers, miners and traffickers increased their presence and work rate. The state’s absence gave them a relative respite from law enforcement, and in Brazil, they were goaded on by Bolsonaro’s anti-environment, anti-Indigenous and anti-science rhetoric.

A combination of road-building, climate change-induced forest heating and drying, and related deforestation is pushing the Amazon rainforest toward a tipping point that could turn the world’s largest rainforest and reserve of terrestrial biodiversity into a sparsely wooded savanna in just a few decades. Thousands of fires were burning in the Brazilian Amazon in September 2022. If the Amazon rainforest becomes a savanna, there will be reverberations in the climates of South America, the Caribbean, North America and across the globe.

The Amazon Borderlands Spatial Analysis Team’s research clearly shows the connection over time (2003-2021) between linear roads, deforestation and forest degradation (in pink on the imagery and maps on the left), and increases in land surface temperature (dark, dark red in the imagery & map on the right). Source: Reygadas et al. 2022/ABSAT/University of Richmond.

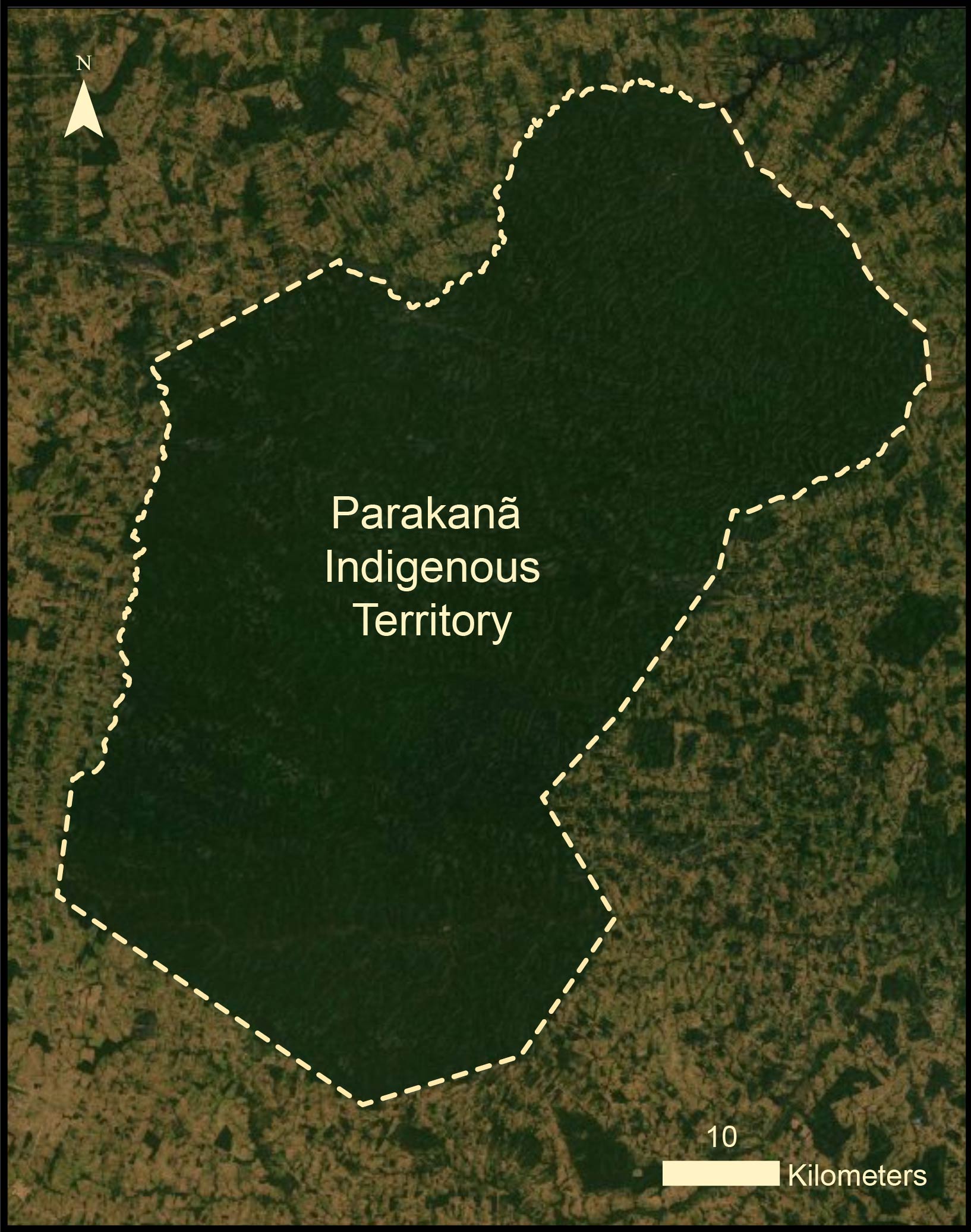

Research shows that Indigenous lands are crucial to safeguarding the forest ecosystems and immense carbon stores. These territories, covering about a third of the Amazon region, act as a buffer against road expansion, reducing both deforestation and fires.

The Indigenous residents of the Amazon borderlands understand that the loggers’ tractors and chainsaws are the sharp point of an ever-expanding illegal road allowing coca growers, land traffickers and others access to traditional Indigenous territories and resources. Currently, there are collaborative efforts by NASA to allow scientists and Indigenous groups to better track the changing Amazon integrating Indigenous ecological knowledge and geospatial analysis of the Amazon rainforest and climate.

A satellite view of the Parakanã Indigenous Territory in the Brazilian Amazon visually demonstrates the ability of Indigenous Territories to maintain standing forest (dark green) despite being surrounded by road-related deforestation and forest degradation (brown, tan and light green). (David Salisbury/ABSAT/University of Richmond)

Many Indigenous residents also realize that their communities may be all that stands in defense of the forest. María Elena Paredes, Ashéninka leader and head of the Sawawo Hito 40 monitoring committee, has faced down the loggers threatening her Amazonian community. She said she represented not just her community and the other Peruvian Indigenous communities, but her Brazilian cousins downstream who also rely on these forests, waters, and fish.

Yet as leaders like Paredes and others defend their forests and people, they are increasingly becoming targets for violence. Global Witness reported that 200 land and environmental defenders were killed in 2021. The killing of journalist Dom Phillips and activist Bruno Pereira in June 2022 was just the latest high-profile attack.

Fifteen years ago, the legendary Indigenous leader Edwin Chota protested the same road that Paredes and her community are blocking today. He and three colleagues were later gunned down in 2014 after receiving death threats from loggers and traffickers. The killers remain free in the borderlands while the survivors struggle. Most of the families of the slain are afraid to return to their forests in the borderland community of Saweto, and instead remain on the outskirts of the city of Pucallpa, squeezed into dilapidated houses with intermittent electricity and clean water. Far from their village, the children cannot build their cultural and environmental knowledge in the forest.

A few hours downriver from where she confronted the loggers, Paredes and other Peruvian Indigenous leaders met with their Brazilian counterparts in September 2022 to discuss strategies to stop the invasions. The Brazilian leaders included Francisco Piyako and Isaac Piyako, two Indigenous Ashéninka brothers who ran for election at the federal and state levels but lost amid the southern Amazon’s conservative turn toward agribusiness.

While the Brazilian election included more Indigenous candidates than any in Brazilian history, with the 175 candidates representing a 37% increase over 2018, few of those candidates won.

Two Indigenous women with strong anti-Bolsonaro platforms emerged from the election as federal deputies: Sônia Guajajara will represent São Paulo state and Célia Xakriabá the state of Minas Gerais.Marina Silva, a former environment minister and past Green Party presidential candidate, also won election as a federal deputy in São Paulo state. None of them directly represents the Amazon.

These results place the future of the Amazon very much in the hands of Brazil’s run-off presidential election on October 30. On one side is Bolsonaro, a populist who has derided Indigenous people, environmentalists and science while weakening environmental and Indigenous agencies and inciting miners, loggers, ranchers and agribusiness leaders to cut down the forest. On the other side is Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – commonly called Lula – a former Brazilian president who is arguing for zero deforestation. Da Silva had 48.4% of the first-round vote to Bolsonaro’s 43.2%.

Peru also held elections on October 2 at the regional and municipal levels. In the Ucayali region, 37% of the candidates were Indigenous. As of October 3, votes were still being counted, but Indigenous candidates have historically had very poor showings. The vote leader for president of the Peruvian Amazonian department of Ucayali is an ex-governor and coca farmer connected to a corruption investigation. In neighboring Madre de Dios, the vote leader for president is a gold miner firmly entrenched in the most socio-environmentally damaging occupation in his department.

In Maria Elena Paredes’ home district, Yurúa, pro-conservation Indigenous residents elected their preferred candidate, providing one of few positive signs for the pro-environment movement in the Amazon.

Without adequate pro-environment and Indigenous representation, the roads and extractive development will march forward, making the Peruvian side of the forest even more vulnerable. A victory for sustainability, conservation and culture in Brazil could resonate across political borders into Peru and the other seven countries that share the Amazon, just as Paredes’ intervention in Peru stopped the tractors from ruining the forests and streams that flow into Brazil.

A version of this article was first published on the Conversation. David S. Salisbury is Associate Professor of Geography, Environment, and Sustainability, University of Richmond.