Nigerien Special Forces trained by the Bundeswehr stand in front of the German Air Force's Airbus A400M in Tillia, Niger during the German defense minister's visit on April 10, 2022. The Bundeswehr is involved in the UN mission MINUSMA in Niger. (Kay Nietfeld/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images)

For the last decade, a unique ecosystem of external forces has deployed over 21,000 uniformed personnel across the Sahel to help address multiple and intersecting political, economic, security, humanitarian, and environmental crises. The United Nations (UN) has deployed a stabilization mission in Mali (MINUSMA); France has led a regional counterterrorism force, Operation Barkhane, and since early 2020, a European Task Force Takuba deployed under French command; the European Union (EU) runs one military training mission in Mali, and two civilian missions in Mali and Niger, all focused on security force and rule of law assistance; and the United States and various other Western countries provide bilateral forms of security force assistance to the region’s states. In addition, since 2017, the G5 Sahel states (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) have deployed a roughly 5,200-strong counterterrorism Joint Force which operates along the region’s porous borders; since 2020, the African Union (AU) has indicated its desire to establish a 3,000-strong force, but so far no troops have deployed; and in March 2022, Niger called for Nigeria to help establish yet another military force to combat militants across the region. (Niger and Nigeria are already part of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), together with Chad and Cameroon, to fight jihadists—primarily Boko Haram—in the Lake Chad basin.)

Despite these missions, security and governance trends across the region continue to deteriorate. During the last two years, four coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Chad (plus a failed attempt in Niger) have increased tensions between external actors and the transitional governments. In Mali, a rapid escalation of tensions resulted in France withdrawing its Barkhane troops from the country. This raises questions about France’s future military presence in the Sahel, but also the consequences for UN and European operations in Mali, which rely on French strategic reassurance in case of attacks and logistical support, such as medical and air support. Furthermore, large numbers of human rights abuses have been committed in Mali by local security forces, jihadists, and presumably Russian mercenaries, in a political climate that Human Rights Watch described as “near total impunity.”

These developments present considerable challenges but also an opportunity to reconsider some fundamental questions: Why are external forces in the Sahel? Can they help resolve any of the region’s crises? And, if so, what configuration of external forces makes the most sense? In this essay, we examine the motives for external military forces and consider the range of plausible options and the key challenges confronting them.

Different external actors have varied motives for deploying forces across the Sahel. They include reducing refugee flows into Europe, degrading jihadist groups, improving local security forces, promoting multilateralism through the UN, reinforcing the EU’s security identity, and strengthening partnerships with allies such as France and the United States. Yet, while refugee flows have decreased, jihadist groups have multiplied, casualties from organized violence have significantly increased, and Russian mercenaries have moved into the region, invited in by Mali’s junta. These developments raise difficult questions about whether and in what configuration external forces should remain in the region. The region’s crises have also drifted further from the public spotlight with considerable media attention prioritizing the war in Ukraine.

Recent developments have also left domestic populations in both the Sahel and Europe increasingly reluctant to support the deployment of foreign forces in the region. In late 2021 in Burkina Faso and Niger, for instance, mobs attacked an Operation Barkhane convoy. European populations are also reluctant to deploy more forces to the Sahel given the related risks, the meager track record, and the focus on Ukraine. Similarly, although the United States is rightly concerned that the French withdrawal in Mali will undermine the other multilateral missions, there is little political appetite in Washington to increase US forces in the region beyond their existing security force assistance roles, especially after four American soldiers were killed in Niger in late 2017. Nevertheless, for the time being, France and its European partners in Task Force Takuba remain committed to retaining a military presence in the region to fight terrorism, focusing on Niger and the countries bordering the Gulf of Guinea. But all the external actors, as well as the AU and ECOWAS, are now grappling with how best to reconfigure and mandate their forces, including whether and how to support MINUSMA.

What are the options for external military missions across the Sahel?

The complex, and not always coordinated, ecosystem of military operations across the Sahel has been aptly labeled a security traffic jam. Here, we will focus on what recent developments mean for the UN, French, and European missions.

MINUSMA

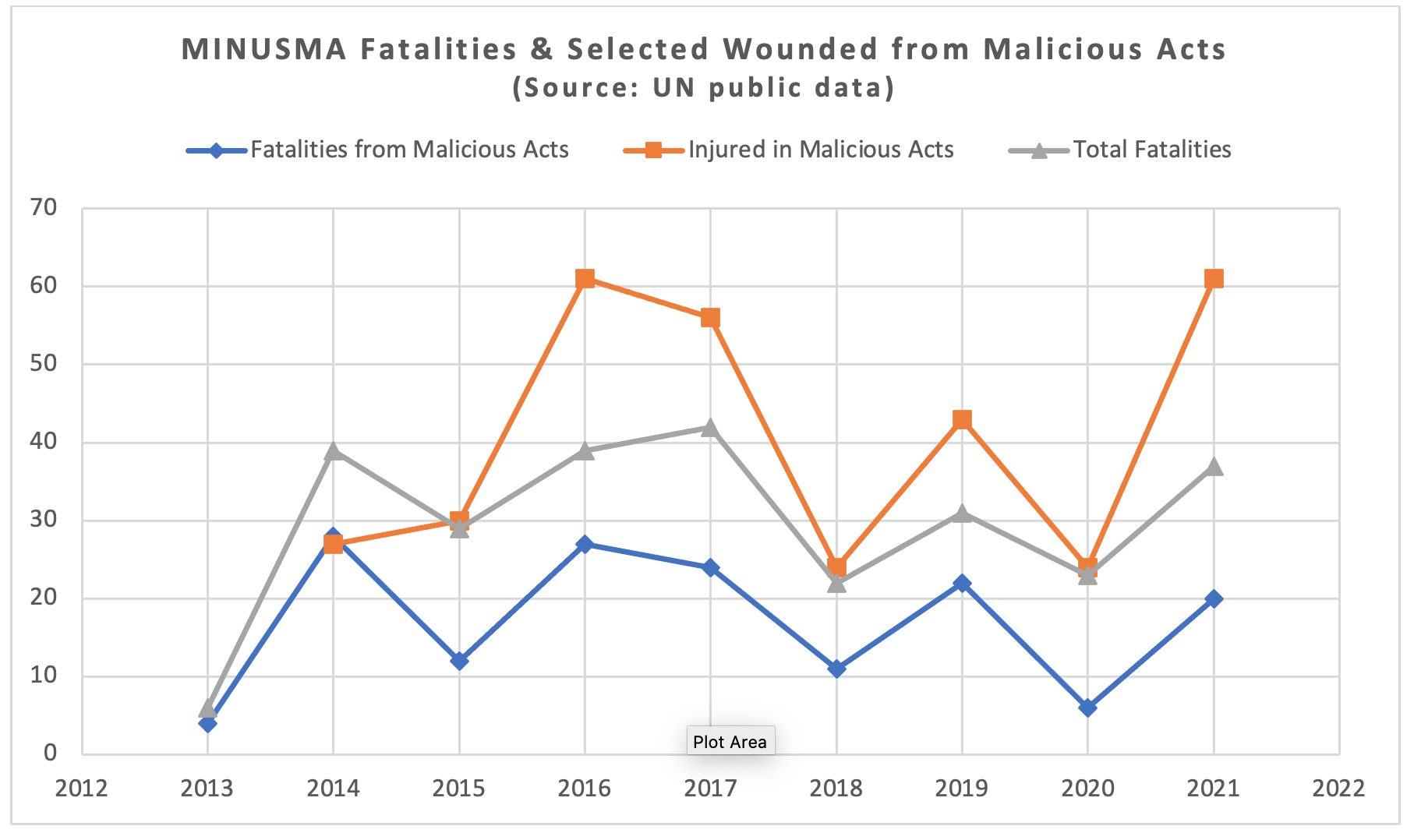

With the French withdrawal from Mali, considerable attention will focus on what this means for MINUSMA. MINUSMA is currently the UN’s most dangerous mission, suffering hundreds of casualties from militant attacks despite devoting considerable resources to force protection. It is also the only UN operation in Africa with over 1,000 European troops, who cohabit—somewhat uncomfortably due to substantial differences in capacity and equipment—with African forces from the region. MINUSMA’s robust and proactive mandate has also raised concerns that the UN is “at war” in Mali, while the high (local and international) expectations placed on the mission’s civilian protection efforts have not been met. Although MINUSMA went through a relatively effective internal transformation since 2018, recent developments have raised questions about its ongoing utility. As French support to MINUSMA is set to disappear by autumn 2022 with the withdrawal of Barkhane troops, and continued French support seems unlikely to be accepted by the Malian junta, MINUSMA’s options could be framed somewhat simplistically as either “go big” or “go home.”

MINUSMA faces an increasingly difficult operating environment: the viability of the Algiers Agreement is in severe doubt, levels of violence are rising, the junta is asserting its power, and Malian security forces are regularly accused of committing massacres, recently with Wagner Group mercenaries. MINUSMA’s relationship with the Malian junta remained functional even as its diplomatic fight with France led to the withdrawal of Barkhane troops, yet following the recent massacres in Moura, allegedly committed by Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA) and Wagner troops, the relationship is likely to deteriorate. The junta only opened an investigation into the massacres a week after they took place, following massive pressure from external observers, while the UN’s demand to access the zone has been denied by the authorities. In this context, continued collaboration with the FAMA seems difficult to imagine. MINUSMA will also soon lose the logistical support and strategic reassurance that was provided by French forces. Here, too, there is no obvious replacement, especially with the US Africa Command’s forthcoming theater campaign strategy adopting a generally reduced posture on the continent.

MINUSMA faces an increasingly difficult operating environment: the viability of the Algiers Agreement is in severe doubt, levels of violence are rising, the junta is asserting its power, and Malian security forces are regularly accused of committing massacres, recently with Wagner Group mercenaries. MINUSMA’s relationship with the Malian junta remained functional even as its diplomatic fight with France led to the withdrawal of Barkhane troops, yet following the recent massacres in Moura, allegedly committed by Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA) and Wagner troops, the relationship is likely to deteriorate. The junta only opened an investigation into the massacres a week after they took place, following massive pressure from external observers, while the UN’s demand to access the zone has been denied by the authorities. In this context, continued collaboration with the FAMA seems difficult to imagine. MINUSMA will also soon lose the logistical support and strategic reassurance that was provided by French forces. Here, too, there is no obvious replacement, especially with the US Africa Command’s forthcoming theater campaign strategy adopting a generally reduced posture on the continent.

“Going big” in such a context will be difficult to sell in New York and Mali: the mission already has a 15,000-strong force and Security Council agreement on reinforcements is unlikely, although not impossible. One problem is whether Russia might block reinforcements to enable Wagner Group to play a more influential role. Another problem would arise if the Malian junta rejected an enhanced MINUSMA or tried to expel the mission. The junta has already significantly decreased MINUSMA’s political and military space in the past year, at one point denying airspace for German drones operating as part of the mission. MINUSMA would find it very difficult to increase its capabilities or stay without the junta’s consent even if, legally, it does not represent Mali’s de jure authorities. Moreover, how can MINUSMA increase collaboration with the FAMA as it stands accused of committing increasingly regular and egregious human rights violations? Finally, even if reinforcements were deployed to MINUSMA, how would the mission plug the logistical support gaps left by France’s withdrawal? For all these reasons, a bigger, stronger MINUSMA looks unlikely.

What about “going home?” Should MINUSMA leave because of this difficult operating environment? MINUSMA’s exit would have several predictable repercussions: it would give jihadist groups greater space to operate; it would leave the civilian population even more exposed to an increasingly authoritarian junta which is committing massacres (sometimes with the Wagner Group); and it would make it much harder, probably impossible, for the EU to restart its Training Mission in Mali. For Western states, withdrawing MINUSMA would also probably result in greater Russian influence in the country. In addition, MINUSMA’s exit would end the main international support mechanism to the G5 Sahel Joint Force: MINUSMA currently provides the Joint Force with life support consumables, engineering support, and casualty evacuation and transport, all of which is financed by the EU. It seems unlikely that the UN Security Council would want to implement the secretary-general’s recommendation to establish a UN Support Office for the G5 Sahel Joint Force without MINUSMA’s presence.

If there is a potential middle way, it probably involves focusing on two potential tasks. First, MINUSMA could prioritize its civilian protection mandate while the UN Security Council seeks to reinvigorate the increasingly moribund Algiers Agreement, or tries to negotiate another peace accord in its place. This might involve doing something like the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) did in December 2013 when civil war broke out and South Sudanese government troops began massacring civilians. Here, UNMISS opened its bases and set up emergency “protection of civilians sites” which housed at one stage over 200,000 civilians at risk. However, conflict dynamics in Mali are different than South Sudan (2013-14) with MINUSMA facing greater risk of attack than UNMISS did. Moreover, such an approach might risk an increase in conflict between local nomads and farmers since the latter might be able to move to such sites more easily. The other route to reconfiguring MINUSMA would be to reduce its footprint and focus primarily on observation and monitoring tasks to document abuses perpetrated by the FAMA, jihadists, and other actors. This type of mission would not be easy to configure and force protection would be a major concern. Nor would it be welcomed by the junta. In sum, there are no obvious good options for MINUSMA.

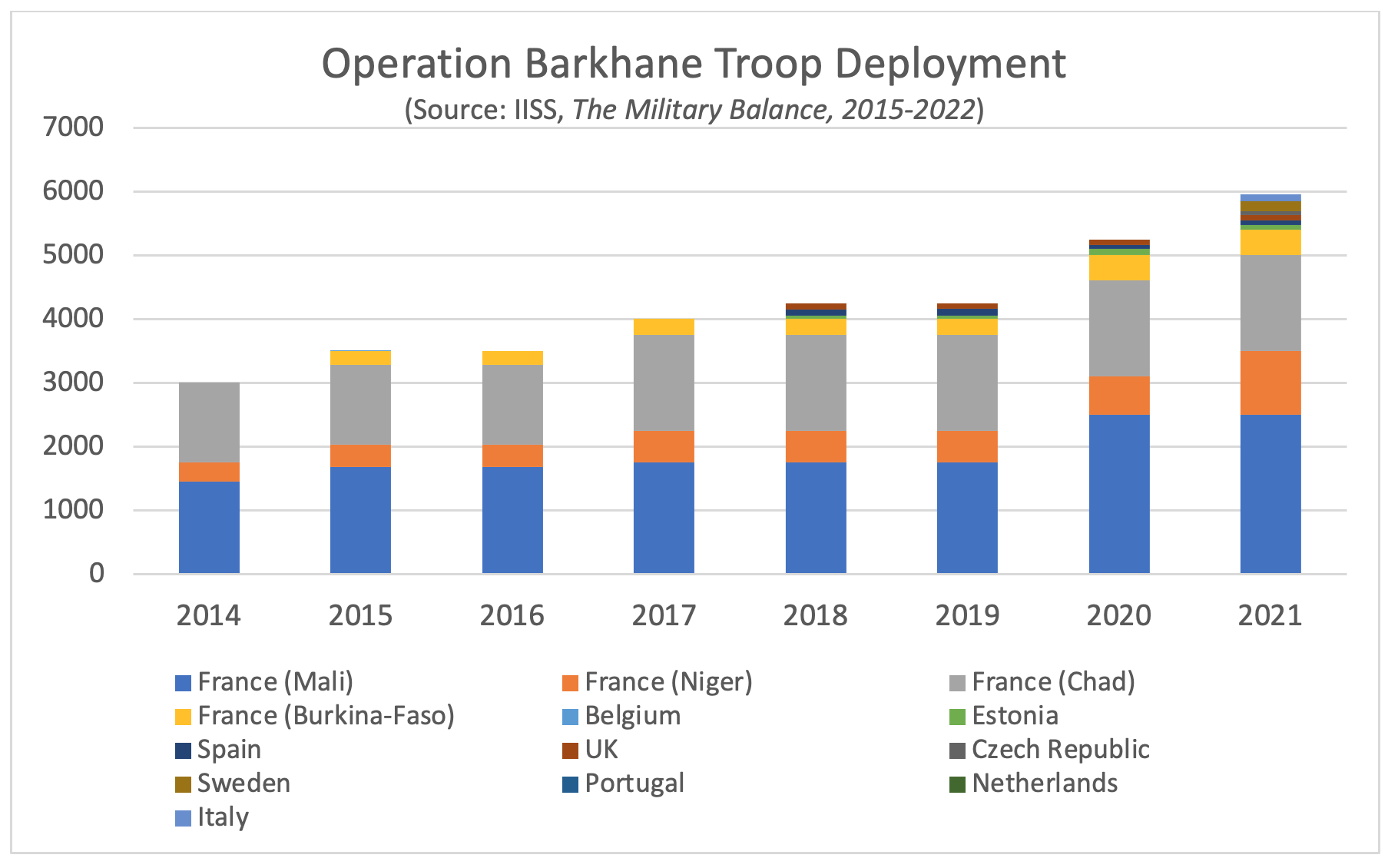

Operation Barkhane (and Task Force Takuba)

France is withdrawing its forces from Mali but is set on retaining a military presence in West Africa more broadly, to target jihadists and prevent their expansion in the coastal states while disrupting non-Western influence in the broader region. France is continuing its combat partnership with Niger, while its “train and equip” efforts for the Nigerien Special Forces remain part of a coordinated bilateral approach with several Western Partner Nations to set up an enhanced Special Forces Command in the country. French “train and equip” programs are also continuing in Mauritania and Chad, while existing military collaboration with the states in the Gulf of Guinea, in particular Côte d’Ivoire, is likely to increase. France’s current priority remains safely withdrawing troops and equipment from Mali before the end of the summer: a logistical challenge that involves significant security risks to the land-born convoys in a volatile, often anti-French environment. How these operations fare and the upcoming French election results are likely to decide the future of possible logistical support to MINUSMA.

France also remains the lead nation for the (at least temporarily) defunct Task Force Takuba. Efforts to maintain the European “Takuba spirit” and decide on future collaborations in the region have resulted in a series of French-led meetings between the Takuba contributing countries. Although Niger’s President Mohamed Bazoum recently made a U-turn by raising the possibility of hosting Takuba troops and openly welcoming these foreign forces, such a redeployment would require new military cooperation agreements between Niger and each Takuba contributing state, thus involving significant administrative and legal work. It therefore seems unlikely that there will be a new, or revived, multilateral coalition concept in the region. More likely is a loosely connected “multi-bilateral” approach between any remaining partners, coordinated and supported by France.

France also remains the lead nation for the (at least temporarily) defunct Task Force Takuba. Efforts to maintain the European “Takuba spirit” and decide on future collaborations in the region have resulted in a series of French-led meetings between the Takuba contributing countries. Although Niger’s President Mohamed Bazoum recently made a U-turn by raising the possibility of hosting Takuba troops and openly welcoming these foreign forces, such a redeployment would require new military cooperation agreements between Niger and each Takuba contributing state, thus involving significant administrative and legal work. It therefore seems unlikely that there will be a new, or revived, multilateral coalition concept in the region. More likely is a loosely connected “multi-bilateral” approach between any remaining partners, coordinated and supported by France.

EU Missions

The EU’s Training Mission in Mali (EUTM) was initially designed to enable the FAMA “to conduct military operations aiming at restoring Malian territorial integrity and reducing the threat posed by terrorist groups,” but in 2018 its mandate expanded to include training and advice to operationalize the G5 Sahel Joint Force. Since 2013, EUTM-Mali has trained over 15,000 FAMA troops. However, following the latest coup, in March 2022, the EU decided to reconfigure the mission and suspend some of its training activities, in part because the junta could not guarantee EU trainees would not collaborate with Wagner Group. The EU has not yet decided whether to withdraw the mission, preferring instead to wait for the results of its ongoing strategic review. This is sensible given EUTM-Mali’s relatively small operational impact on the FAMA and the latter’s increasingly regular human rights violations. The EU should not ignore its conditionalities for training missions when faced with a junta that is explicitly endorsing violations and aligning with Wagner Group.

In comparison, the EU has more room to bolster its assistance mission in Niger (EUCAP Sahel). However, given current domestic opposition to foreign forces in the country, and the possible increase of bilateral troops from the defunct Task Force Takuba, this does not seem like a viable option at the moment. Finally, the EU must also decide what to do with its financial and technical non-lethal support to the G5 Sahel Joint Force, currently totaling about €70 million annually. The Joint Force has had limited success concerning cross-border operations, given sovereignty issues between its members and the principal focus on domestic operations. Some leading observers have lamented that it is often a G2 or a G3 Force, but rarely a G5 Joint Force. The lack of efficient coordination and collaboration has been exacerbated by ECOWAS sanctions on Mali, which has resulted in closed borders between the countries. This situation, in combination with a significant number of human rights abuses by the Joint Force, raises important questions about whether external partners should continue to support the coalition and, if so, how best to do that. As noted above, this is partly a debate about whether the UN should establish a Support Office for the Joint Force, or whether that would be a bad idea.

Conclusion

Today, the future of Western external military operations in the Sahel region looks bleak. Most assessments of them identify serious problems and limitations: military defeat of the transnational, networked, and locally-embedded jihadists is unrealistic; the sheer size of the territory with the forces available makes the objective impossible to achieve; and recruitment for the non-state armed groups continues because of the absence of state authorities, bad governance, and security forces’ human rights abuses. At best, therefore, these missions can observe and report transgressions and abuses by local security forces and non-state armed groups, contain and degrade the latter, and thereby prevent a very bad situation from becoming even worse. At worst, however, these missions may have contributed to increasing levels of political instability and violence across the region by fueling the narratives that enable non-state armed groups to attract recruits.

The current situation in the Sahel, and in Mali in particular, is thus worrying and increasingly complex. Withdrawing all Western external military actors means that the civilian population, which already has suffered significantly over the past decade, is left in the hands of local security forces and Russian mercenaries in an increasingly authoritarian climate, characterized by impunity. Yet, maintaining a military presence against the will of the Malian junta will be difficult, not only because of the very constrained options to act, but also because of possible counterproductive effects in the form of attacks against the operations or the civilian populations supporting them. The fundamental problems for international military missions are that no single actor can cope with the Sahel’s challenges alone, and no external actor can solve the underlying causes of these challenges without active cooperation from local partners. As the external military options in Mali constrict, perhaps now is the time for international actors to emphasize the two “Ds” of diplomacy and development in how they respond to the multiple crises facing the Sahel.

Nina Wilén is Director of the Africa Programme at the Egmont Institute for International Relations and Associate Professor at Lund University. Her latest book is African Peacekeeping (Cambridge University Press, 2022). She tweets at @WilenNina.

Paul D. Williams is Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University. His latest book is Understanding Peacekeeping (Polity Press, 3rd edition, 2021). He tweets at @PDWilliamsGWU.