A wide view of the Peacebuilding Commission in 2020. (UN Photo/Loey Felipe)

There is a growing consensus that climate change exacerbates existing risks of conflict and violence. Yet, within the United Nations, there is a lack of agreement among member states on which organs are most appropriate to respond to climate-related security risks. The Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) has demonstrated a growing role as a forum for member state discussions on this issue. Analysis shows that the PBC’s emphasis on national ownership and its mandate to work across the peace and security, development, and human rights pillars of the UN; to bring together the Security Council, the UN’s Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), the General Assembly, and other organs of the UN; and to convene relevant stakeholders from within and outside the UN system, may make it uniquely positioned as a forum for states to seek international support to emerging climate-related security challenges.

The PBC format and the nature of its agenda, in which member states voluntarily seek PBC engagement, may provide a more accessible and acceptable forum than the UN Security Council. This is because countries affected by climate-related security risks can generate high level political attention and mobilize funding. The PBC’s diverse membership provides a broad range of perspectives on climate-related security risks, which may enable it to navigate political and organizational obstacles to addressing climate-related security risks more effectively than the Security Council—despite some of the strongest opponents to this issue in the Security Council also being PBC members. The fact that PBC engagement is based on national ownership and partnership—in which countries choose themselves to come to the PBC to discuss their nationally-owned peacebuilding priorities—can ease barriers for discussing thematic issues that are otherwise contentious. Lastly, the format is also more accessible for climate security experts.

Strengths notwithstanding, there are obstacles to the PBC becoming a useful forum to discuss climate-security, primarily around the way the PBC is structured and has been utilized, and political considerations.

Climate-Related Security Risks in the Peacebuilding Commission

Within the UN, the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has the lead role in organizing member states to limit greenhouse gas emissions. There is also the ECOSOC and the second committee of the General Assembly, which spearhead efforts to adapt to climate change and invest in low-carbon development, and the Security Council which is responsible for the maintenance of international peace and security. However, neither the UNFCCC, ECOSOC, nor the second committee addresses the intersection of climate change with peace and security, and climate change does not regularly feature on the agenda of the latter. Meanwhile, many have concerns about the Security Council’s role, despite its recurrent engagement on the issue since 2007.

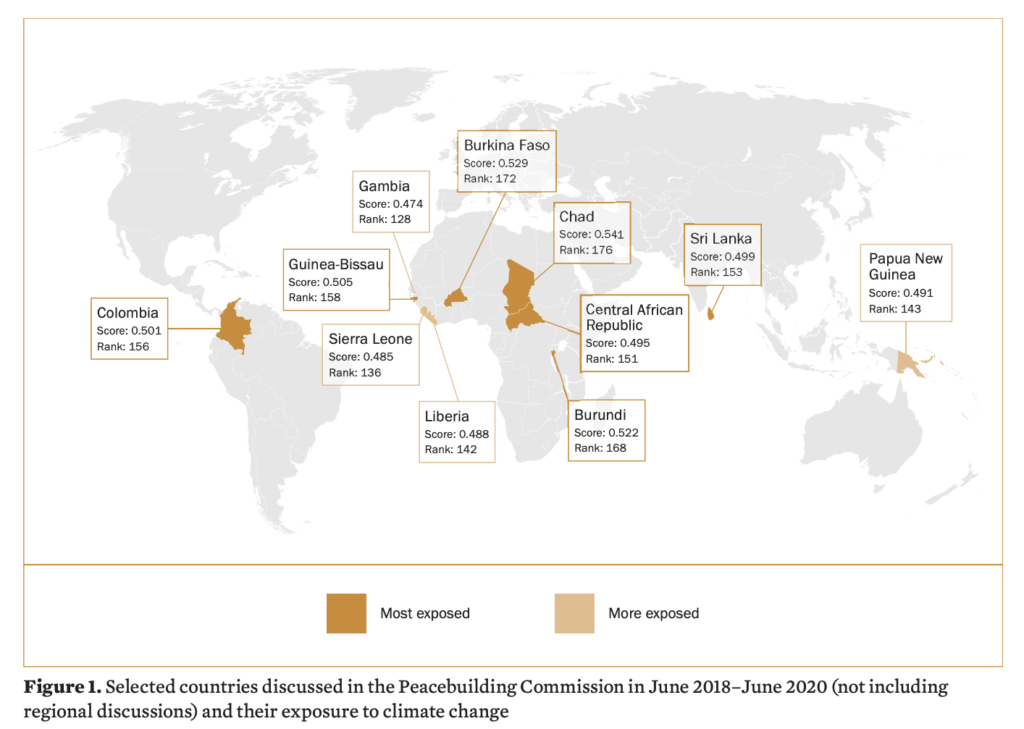

Although the PBC does not have an explicit mandate to focus on the linkage between climate change and conflict, its foundational resolutions emphasize the role of the PBC in promoting an integrated approach that bridges the UN’s work in peace and security, human rights and development. As such, the PBC has increasingly become a forum in which climate change is raised, in the context of its consequences for conflict prevention and peacebuilding, particularly in regional discussions on the Sahel, Lake Chad Basin, and most recently, the Pacific Islands.

Yet the political sensitivities and divisions that have characterized debates on the relationship between climate change and security that are so visible among UN member states in the Security Council are also apparent in the PBC. These divisions do not follow clear global North/South boundaries: European countries like Germany, Sweden, and France have diverse allies in Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific in being strong supporters of the PBC taking a more active role on climate-related security issues.

Instead, these divisions reflect contested views about the mandate of respective UN legislative bodies; the most appropriate tools for the UN to respond; and, for a very small minority of countries, the causes of climate change and their relationship to phenomena like drought and land degradation. Taken together, these divergent concerns determine the extent to which the PBC is able to set its agenda, and the ways in which it can discuss climate-related issues.

The Politics of Discussing Climate-Related Security Risks in the PBC

The extent to which the PBC is able to become a forum for discussions on climate-related security risks and to provide climate-related advice to other member state bodies is influenced by its members’ views on the mandate of the commission; their position on the causes (if not reality) of climate change, including whether and how these influence insecurity and violence; and their opinions on the most appropriate forms of response by the UN.

One factor that influences the ability of the PBC to address climate-related security risks to peacebuilding is its mandate. Before the commission discusses any topic, whether geographic or thematic, member states careful about first ensuring that the PBC has a mandate to do so. PBC diplomats, including those from China and Russia, emphasize the importance for both countries that the Security Council maintain its prerogative on international peace and security and that the PBC retains its advisory role on such issues. Russia and China, as well as some Global South countries like Brazil, also argue that climate change is a development issue and should be dealt with elsewhere—through ECOSOC, the Second Committee of the General Assembly, and the UNFCCC.

Other permanent and elected members of the Security Council, including France, Germany, and Sweden (which served on the council from 2017–18), have taken a more proactive approach to using the PBC’s advisory role. France is represented in the PBC as one of the P5. Germany and Sweden, both current members of the PBC, also served back-to-back terms on the Security Council. In both bodies, they have sought to strengthen the PBC’s advisory role, including through the ongoing 2020 review of the peacebuilding architecture and thematic consultations, and pushed for greater attention to climate-related security risks, including through the addition of climate-specific language in several peace operation mandates.

Regional Approaches on the Sahel and the Pacific

Despite the differences among member states, the consequences of climate change have become a regular aspect of PBC discussions with a country-specific or regional focus—particularly where there is vocal support from the country’s or region’s governments—including in the country-specific configurations (CSCs) and, since 2017, a series of meetings on the Sahel. With the participation of the countries in the region, the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel, the African Union (AU), the European Union (EU), the G5 Sahel, and the UN system, the PBC’s Sahel meetings “have focused on ways to overcome the region’s multi-dimensional challenges by addressing the root causes of crisis pertaining to social, economic and environmental factors.”

The Sahel is the only geographic area where the PBC has an explicit mandate to support efforts to adapt to the effects of climate change, specifically implementation of the UN Integrated Strategy for the Sahel, and has been the topic of informal interactive dialogues (IIDs) with the Security Council in 2019 and 2017. The 2017 IID on the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin was a turning point in the PBC’s relationship with the Security Council, as the first substantive discussion between the two bodies on countries and regions, and the beginning of the PBC’s engagement on climate-related risks in the Sahel. That meeting directly influenced and provided political space for the joint annual meetings of the PBC and ECOSOC in 2018 and 2019. The PBC/ECOSOC meeting in 2018 explicitly focused on “Linkages between Climate Change and Challenges to Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace in the Sahel” and, in 2019, on “The Impact of Cross-border Transhumance on Sustainable Peace and Development in West Africa and the Sahel.”

The onset of COVID-19, however, has provided a new opening for the PBC to consider the impact of climate change. In the context of the PBC’s engagement on how the pandemic is impacting peacebuilding, it has organized regional meetings on Central Africa, the Great Lakes, the Lake Chad Basin and Pacific Islands. The open meeting on the Pacific Islands, convened at the request of Fiji, in close consultation with Tuvalu (the current chair of the Pacific Islands Forum), was among the most explicit discussions on climate-related security risks to date.

Move Slowly, Steadily, and Forward

The PBC has demonstrated a growing role as a forum for member state discussions on climate-related security risks in its own right. In recent years, it has gradually increased the attention given to climate-related security risks across a range of countries; engaged in joint meetings with ECOSOC; provided advice to the Security Council; and provided a forum for affected states and champions of this issue to make statements that call attention to the real-life linkages between climate change and other drivers of instability.

Nonetheless, there is a danger that efforts to advance this agenda too quickly—or to view it as a stepping stone to greater Security Council engagement on the issue—will backfire. Several countries have used this opening to try to make a “big push” on climate, calling for thematic discussion in the PBC or for it to develop a climate strategy, akin to its strategy on gender. Yet the majority of PBC members favor a more gradual, more creative approach, which they see as likely to prove more constructive in the long run. This approach would encourage more countries to seek support from the PBC in relation to climate and security, providing a larger base of “lived experience,” and narrowing the political space for climate-change skeptics.

In coming years, climate change will continue to amplify drivers of violence, displacement, inequality, and marginalization. Such risks are likely to become more prevalent and affect a growing number of countries. As the UN marks its 75th anniversary in 2020, many of its institutions—including the Security Council—are showing signs of strain, struggling to adequately respond to, and stay relevant in, a rapidly changing and increasingly complex world. As one of the more recent additions to the UN system, the PBC has taken time to find its place amid the constellation of other, more powerful, more established, or more operational entities. As the UN system adapts to climate-related security challenges, and to the needs of member states and their societies, the PBC will have a critical role to play.

Jake Sherman is Senior Director for Programs for the International Peace Institute. Dr. Florian Krampe is a Senior Researcher in the Climate Change and Risk Programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). He specializes in the research areas of peace and conflict, environmental and climate security, and international security.

This article is part of a series on climate change and was adapted from a recently published report by SIPRI and IPI.