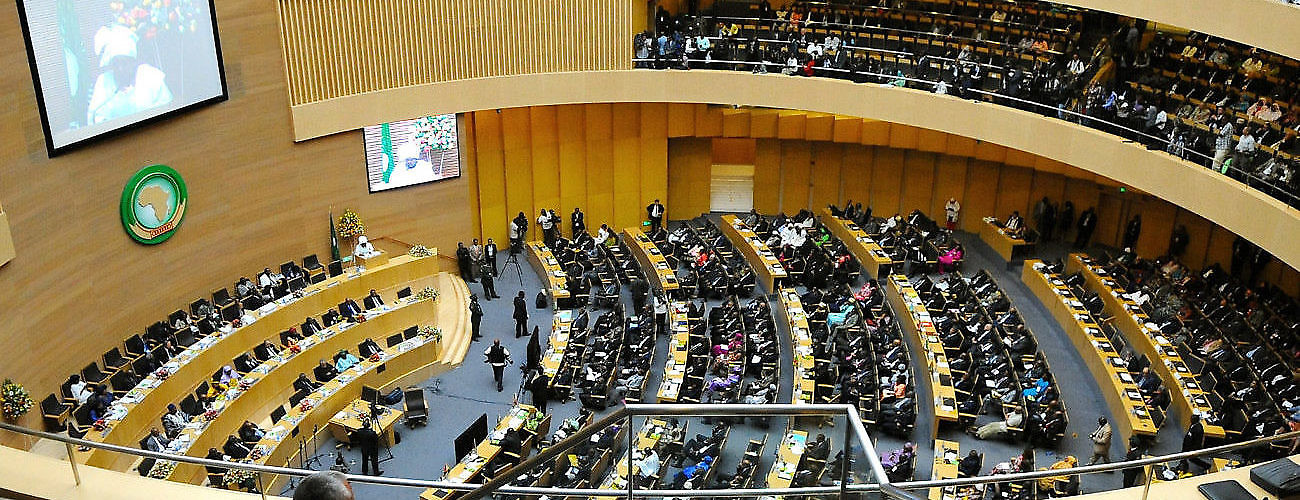

View of a plenary session of the AU Assembly at the Nelson Mandela Conference Hall in the African Union.

Despite positive momentum to ensure greater coherence and effectiveness in United Nations peacebuilding, longstanding political crises, transnational threats, and the interference of external political actors continue to impede tangible progress on-the-ground. The need to refine a coherent global peacebuilding system has been continuously worked on since the establishment of the UN’s Peacebuilding Architecture (PBA) in 2005, which has been subject to major institutional and policy-level reviews every five years.

The third, ongoing, review of the PBA follows from the landmark 2016 sustaining peace resolutions and is expected to conclude by the end of 2020. While it is not likely to break new conceptual ground or revolutionize current approaches, it is nonetheless an important juncture for affirming recent gains and for evaluating progress on key areas. Peacebuilding partnerships are one such area, and the UN partnership with the African Union (AU) is critical to this focus.

The Common African Position (CAP) prepared by the AU and endorsed by the AU Peace and Security Council is a valuable input to the PBA review. It articulates African peacebuilding priorities and identifies opportunities to improve multilateral peacebuilding on the continent, informed by lessons from the AU’s post-conflict reconstruction and development (PCRD) efforts. It therefore provides an important lens for reflecting on the future of a global peacebuilding architecture and for understanding how stronger UN-AU cooperation on peacebuilding—which to date has been the weakest part of the partnership—can contribute to this architecture.

The Common African Position highlights challenges that are relevant to the PBA review. UN and AU partners, for example, grapple with differences over the political strategies for peacebuilding, the contested nature of local ownership, and longstanding conceptual differences in their respective peace and security frameworks.

Peacebuilding is inherently political, and aligning strategies between different multilateral organizations is a constant back and forth. The UN and the AU are not immune to this challenge. Each country or region discussion requires a shared definition of challenges and priorities, more nuanced understanding of political legitimacy, and a balance between inclusivity and targeted engagement. While the CAP unpacks many thematic priorities, it does not provide a broader theory about how to foster closer political cooperation at the member state or operational levels. This challenge is exacerbated by the realities that neither the AU Peace and Security Council nor the UN Peacebuilding Commission are solely responsible for shaping multilateral political strategies in the countries where they engage, as the UN Security Council, the AU Assembly and the continent’s regional economic communities/regional mechanisms all influence these political trajectories.

Local ownership is at the heart of effective peacebuilding, but this often comes into tension with the tendency for state-centric pushes for multilateral peacebuilding. The relationship between national authorities and local peacebuilding actors can often be tenuous in post-conflict settings, and becomes even more fraught when balancing peacebuilding and politically contentious issues like stabilization, justice, security, and governance. The CAP rightfully highlights the importance of local peacebuilding as necessary for national ownership. However, African members situate cooperation between state and non-state authorities as technical and participatory issues, instead of the deeply political debates they represent.

Continued differences in peacebuilding terminology between the different organizations also complicates efforts to pursue collective action. Despite an intentional effort within the CAP to closely link conflict prevention and peacebuilding (and resolve some differences between sustaining peace and PCRD terminology), the document frequently uses post-conflict reconstruction and development, peacebuilding, sustaining peace, and stabilization to describe different stages of peacebuilding work. This has the unintended consequence of frustrating efforts to foster a more coherent conceptual and operational understanding of peacebuilding work.

Nonetheless, the CAP provides an important lens for reflecting on the future of a global peacebuilding and how a stronger UN–AU partnership can contribute to this.

The CAP is a marker of African political unity and signals consensus around why peacebuilding is important, and how the UN should improve its approaches. While PCRD is a long-standing part of the continent’s peace and security architecture, it has been implemented inconsistently and received less attention compared with mediation efforts and peace support operations. And even though Africa is a prominent focus of UN peacebuilding (both at the political level and at the implementation level), African member states have been comparatively less vocal and unified on peacebuilding issues on the UN Peacebuilding Commission compared with their engagements in the UN Security Council.

With aligned political strategies at the heart of a closer UN-AU partnership, the CAP will likely be a valuable anchor for more coherent political engagements on peacebuilding by African member states across both Addis Ababa and New York. It will serve as a reference point for African member states engaging on peacebuilding discussions in the UN Peacebuilding Commission and in the UN Security Council.

Continental approaches to peacebuilding are expanding to now encompass a broader subset of the AU’s peace and security work, a notable departure from the post-conflict lens that initially defined African peacebuilding efforts. Member states used the CAP to endorse concrete recommendations on peacebuilding and its interlinkages with a wide range of issues, including: financing, conflict prevention, post-conflict transitions, governance and inclusive institutions, transitional justice, women, peace, and security, youth, preventing and combatting terrorism and violent extremism, and health. The AU has also begun shifting its approach from traditional post-conflict settings to a wider range of contexts, bringing it closer in line to the UN’s continuum approach to sustaining peace and the direction of the UN-AU partnership.

Increased financial support for peacebuilding is intentionally situated as the first of Africa’s peacebuilding priorities. This emphasis aligns with the UN secretary-general’s recent warning that “adequate, predictable and sustained resources for peacebuilding remains our greatest challenge.” Given that a lot of UN peacebuilding funding is already spent on the continent, African member states’ support for a suite of policy proposals on peacebuilding—including those fiercely debated following the UN secretary-general’s 2018 report—is an important demonstration of political commitment. Encouraging closer relationships between the UN, the AU, and international financial institutions like the World Bank and African Development Bank is also a welcomed push for closer multilateral cooperation, especially as the AU Development Agency begins its work.

Improving operational collaboration on peacebuilding between the UN system and the AU Commission is another step towards a stronger global peacebuilding architecture. African member states support the two organizations pursuing more frequent consultations, undertaking joint visits to conflict-affected countries and regions, developing common analytical products, reports and evaluations, and aligning advocacy campaigns for development funding. Many of these tools already feature across other areas of UN-AU cooperation and their incorporation into peacebuilding settings represents the next steps in the partnership’s gradual evolution.

Despite these differences, the CAP is an important step forward in helping member states and the organizations identify areas of convergence and divergence in peacebuilding cooperation. The political unity of purpose and the operational clarity embedded throughout the CAP is crucial for guiding the next stages of multilateral peacebuilding. Africa’s experiences and expertise across peacebuilding areas positions it well to shape new solutions, especially as no one multilateral organization single-handedly provides effective peacebuilding support throughout the African continent.

This unity of purpose is also necessary for fostering a stronger the UN-AU partnership, which can serve as the backbone of a nascent global peacebuilding architecture. The processes through which the UN, the AU, and their member states continuously articulate shared values, negotiate political objectives, and identify their complementarities and limitations can be models for peacebuilding partnerships elsewhere.

This article is published as part of a joint project between IPI and ISS on the UN-AU partnership in peace and security. A version of it was also published in ISS Today.