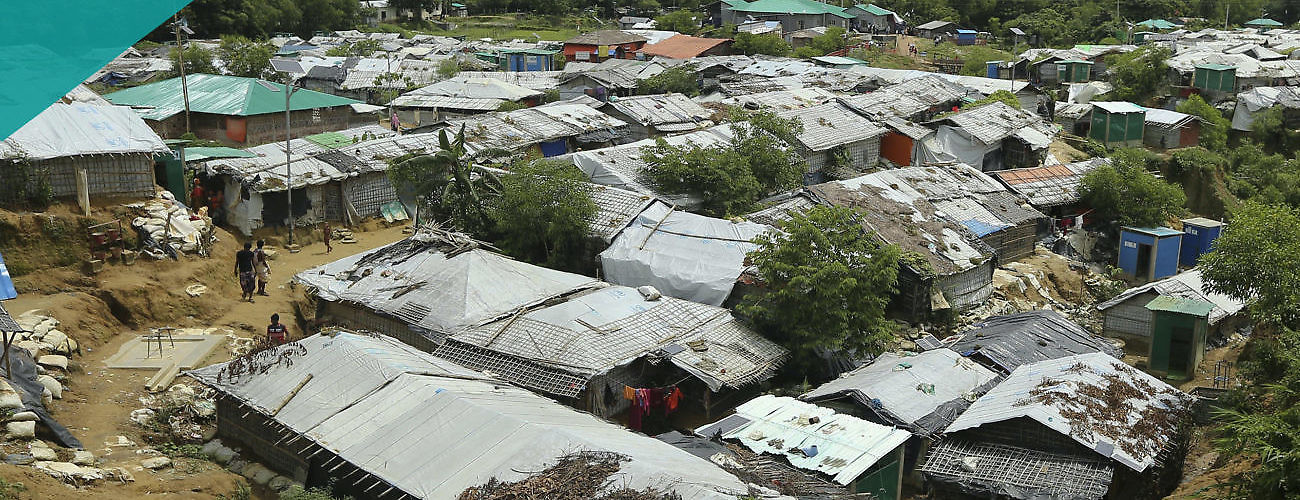

A general view of Nayapara Rohingya refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Sexual violence against the country's Muslim Rohingya minority was so widespread and severe that it demonstrates intent to commit genocide, and warrants prosecution for war crimes and crimes against humanity, according to a United Nations report. (AP Photo/Mahmud Hossain Opu, FILE)

Adopted in April, United Nations Security Council resolution 2467 represents a crossroads for UN member states who are invested in securing and protecting the fundamental rights of all women and girls affected by conflict. The absence of explicit mention of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) signifies a new threat of future attacks on SRHR guarantees across the multilateral system, and ultimately on the lives and dignity of women and girls.

Despite the political warning in resolution 2467, the normative framework that secures SRHR in conflict remains intact following its adoption. The affirmation of the eight preceding women, peace, and security (WPS) resolutions assures that previously agreed language on SRHR protections is secured. The inclusion of explicit reference to the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and its optional protocol also reflect specific SRHR guarantees.

The addition of CEDAW general recommendation 30 arguably goes further and strengthens reference to existing state obligations that provide access to safe abortion in conflict within the WPS agenda. Modest gains were also made through the inclusion of a newly-articulated, survivor-centered approach to accountability narrowly focused on documentation and prosecution, access to justice, and, to a lesser extent, civil society participation and protection. None of the content of the final resolution, however, justified the use of the fundamental rights of women and girls as part of a language trade in the negotiation.

It is arcane to suggest that providing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services to survivors of conflict-related sexual violence is even up for debate. All women and girls need and have the right to access to SRH services, but arguably nowhere is that need more acute than in conflict settings. Today we face an unprecedented level of conflict and crisis around the world and the highest levels of associated displacement on record. Current estimates indicate that over 135.3 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance globally. In 2015, these figures included 26 million women and girls of reproductive age, a figure most likely to have grown since.

The gendered natured of conflict compounds the existing multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination already experienced by women and girls. Rates of sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls increase exponentially during conflict. This violence, the central topic of resolution 2467, is and should remain shocking and unacceptable. It includes rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, marital rape and child, and early and forced marriage. While victims include men and boys, conflict-related sexual violence continues to disproportionally impact women and girls, who face further unique consequences such as forced, unintended, and unwanted pregnancies.

In addition to being a serious human rights violation, conflict-related sexual violence can lead to high rates of unsafe abortion, maternal and low birthweight, miscarriage, premature labor, and sexually transmitted infections for women and girls. The added context of disintegrating health systems, unsafe environments, prohibitive costs, lack of information, fear of violence for seeking care, and pre-existing legal, policy, and social barriers presents unique challenges for ensuring available, accessible, acceptable, and good quality SRH services to women and girls affected by conflict.

Despite this clear need, and the presence of existing state obligations under international human rights law, explicit reference to SRH services for survivors of conflict-related sexual violence was removed from the draft resolution on April 23 in response to the threat of a veto by the United States. For those of us monitoring the current US administration, the veto threat was in fact not a surprise. Despite established constitutional rights to access to safe abortion in the US, the current administration has attempted to restrict SRHR for women and girls globally since Donald Trump’s election in 2016. The central takeaway from resolution 2467 is a confirmation of the lengths this US administration is willing to go to attack the rights of women and girls beyond its own borders. This outcome adds to a growing list of extra-territorial attacks, including the recent decision to extend the reach of the “Global Gag Rule,” which creates restrictions to SRH services globally through the misuse of development assistance.

The question left for UN member states invested in protecting SRHR in conflict is: what now? How will the promise of feminist foreign policy agendas and commitments to SRHR protections within the multilateral system translate in the face of this clear and muscular threat? As shown by the number of national and cross-regional statements supporting SRHR during the April Security Council Open Debate on Conflict-Related Sexual Violence, many states are willing to speak up. The extent to which this rhetorical support translates into outcomes in the Security Council and lifesaving work on the ground will be revealed in whether states are prepared to fund the provision of SRH services in conflict, and whether the inclusion of SRHR protections does in fact represent a red line in their negotiations moving forward.

Siri May is the Senior Global Advocacy Advisor at the Center for Reproductive Rights.