US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley chairing the Security Council meeting on UN peacekeeping operations held in September. (UN Photo/Manuel Elias)

Paying the bills for United Nations peacekeeping is complicated but not only has the administration of US President Donald Trump failed to pay its official assessed rate, it has also failed to release funds appropriated by the US Congress for that purpose. As of September 30, the US was behind by approximately $1.22 billion in unpaid UN peacekeeping assessments. The delay in payment is having negative effects.

Nearly 103,000 peacekeepers are currently deployed in fourteen UN missions, some of them in protracted war zones. The “Big Five” UN operations are in Mali, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, and Sudan. They account for about 81,850 of those peacekeepers and cost about $4.63 billion or 69 percent of the overall annual bill for UN peacekeeping, currently $6.69 billion for the 2018–19 fiscal year—although this amount only reflects six months of the UN-AU Hybrid Operation (UNAMID) in Sudan.

Paying for UN Peacekeeping

Paying the bills for UN peacekeeping operations is complicated. While the UN’s special political missions—comprised of mainly civilian personnel—are paid for out of the UN’s regular budget, paying for most peacekeeping missions involving military and police contingents is much more complicated for several reasons. The only two exceptions are the UN Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) in the Middle East and the UN Military Observer Group (UNMOGIP) in Kashmir, which are paid for from the regular budget because they were established before the current financial system was created.

First of all, it’s impossible to predict how much peacekeeping will be required in any particular year, especially given the possibility of establishing new missions to respond to crises. The costs can therefore increase significantly and unexpectedly.

Second, there is no single, permanent budget for UN peacekeeping because despite being the organization’s most visible activity peacekeeping is still not officially considered one of the UN’s core functions for budgetary purposes. Instead, each mission has a separate budget. There are also two additional accounts which cover logistics and headquarters support costs, but these are paid for out of each peacekeeping mission budget. It is debatable whether operating multiple separate mission budgets helps ensure better financial management than a single, fungible account. But the latter would certainly provide greater flexibility and help with issues concerning inter-mission cooperation.

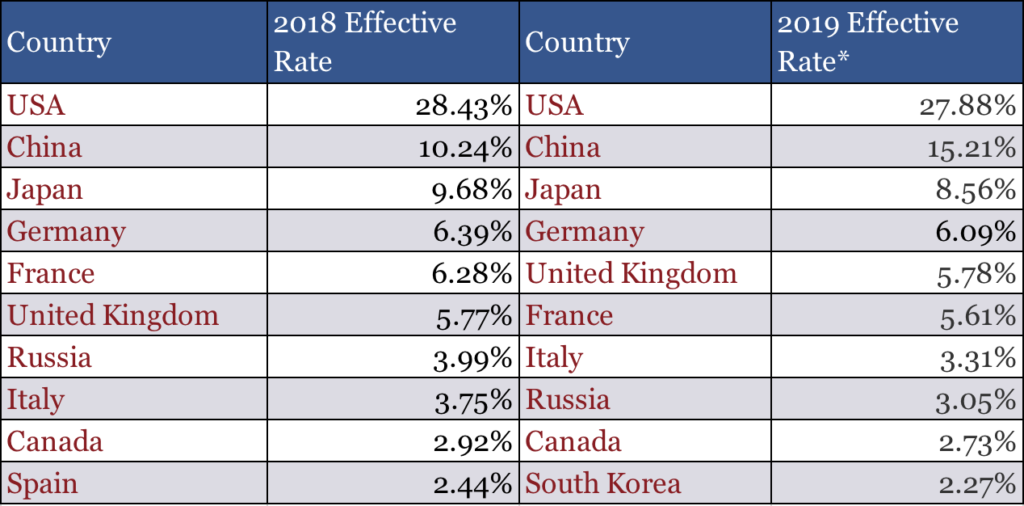

Third, all UN member states are expected to pay a slice of the overall annual bill for peacekeeping, but the slice varies considerably. The rates of assessment are the product of international negotiations in the General Assembly that take place every three years. These negotiations agree on a formula which the UN then uses to calculate the assessed rates for each member state, which reflect the updated economic data. The formula takes into account each country’s share of the UN regular budget, to which countries with lower per capita incomes are granted discounts which are offset by additional payments (a “premium”) paid by the permanent five members of the UN Security Council to reflect their role in peace and security. The approximate effective rates for peacekeeping in 2018 and 2019 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Top Ten Financial Contributors to UN Peacekeeping Operations (Approximate Rate of Assessment)

*The 2019 rate has been calculated by the UN based on the formula approved for 2016–2018 but updated to reflect new economic data; the actual rates will be set by the General Assembly before the end of the year (source: 2018; 2019).

Fourth, the payment of assessments in full and on time is important because the countries that contribute peacekeepers in the field rely on a system of reimbursements from the UN. These reimbursements are intended to help reduce the financial barriers that contributing countries face in their efforts to help maintain international peace and security by participating in peacekeeping. Personnel reimbursement reduces the cost of common and essential additional costs such as vaccinations and training but doesn’t cover salaries and benefits. There is a separate system for reimbursing equipment. The UN calculates the relevant reimbursements and pays them subject to various conditions being met, such as signing a memorandum of understanding with the contributing country and having sufficient cash available. Consequently, if the UN’s member states don’t pay their contributions in full and on time, it is likely to be the countries contributing the most peacekeepers that suffer financially.

The United States and Peacekeeping Finance

Since this system of financing UN peacekeeping operations was established in the 1960s, the US has always been assessed as the top financial contributor. Currently, the US assessed rate for peacekeeping is just over 28 percent or about $1.4 billion for the 2018–19 fiscal year, considerably more than any other country. At one stage in the 1990s, the US assessed rate was nearly one-third of the total UN peacekeeping bill. In 1994, however, the US Congress unilaterally imposed a financial cap, saying it would pay no more than 25 percent of the bill for UN peacekeeping.

Since then, there have been two options for the US to address the gap and pay its full assessed contribution to UN peacekeeping: changing the cap or finding other mechanisms to make up the difference. For most of the years between 1995–2012, Congress decided to lift the arbitrary 25 percent cap on contributions, allowing the US to pay its full assessed rate. Beginning in 2013, the administration of President Barack Obama had to use “credits” to bridge the difference between the approximately 27 percent that was paid and the approximately 28 percent that was officially owed to the UN. Credits arise when a mission underspends its appropriated budget and monies are rolled over to the next fiscal year. Whether there is any credit for a particular mission and how much thus varies across missions and from year to year. The US Congress can also prohibit their use. In 2017, when Congress re-imposed the 25 percent cap, the Trump administration decided against using credits to make up the shortfall and hence the US began accumulating arrears.

Today, the gap between the 25 percent Congressional cap and the official US assessed rate of 28.4 percent translates to approximately $480 million for 2017 and 2018. At this rate, after four years, the US will have wracked-up nearly $1 billion in peacekeeping arrears. This would be bad enough, but the additional problem for the UN is that the US isn’t paying the full 25 percent either.

This is due to a strange situation that might be unique in modern US history. In both fiscal years of the current administration, the US Congress has rejected President Trump’s initial budget proposal on UN peacekeeping (and UN funding generally), the first of which proposed drastic cuts for peacekeeping missions amounting to $1 billion. Instead, Congress appropriated funds that were very close to the amounts for previous fiscal years. Normally, the bulk of these funds would be paid to the UN in September; in fact, for every year since at least 2010, the US has made payments ranging from $1.32 billion to $2.23 billion in that month alone. In 2017, the Trump administration continued this trend and made a September payment of $1.32 billion for UN peacekeeping. But this year, the US has so far paid only $992 million, even though Congress appropriated far more—$1.38 billion—months ago. This has left a shortfall for the UN of $413 million. While the UN secretariat can shuffle some existing monies around in order to stop this shortfall from immediately impacting the countries that contribute peacekeepers, that short-term fix is not sustainable. At the very least, the US government should communicate clearly to the UN and the public how much it intends to pay and when.

This tactic is not just about peacekeeping. It is part of a broader strategy that the Trump administration has reportedly adopted to avoid paying money to various UN agencies and institutions that it does not want to support, despite Congress appropriating money for that purpose. The plan was reported to involve using “bureaucratic levers—such as imposing onerous accounting and reporting requirements—to kill off programs the White House opposes while Congress was still funding them.” If this is the case, then further reducing the UN peacekeeping budget as called for repeatedly by US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley won’t solve the problem but it will simply reduce the size of US arrears.

President Trump’s administration is not the first to argue that the US assessed rate should be reduced. And here they are on solid ground. As the current looming crisis underscores, it is unwise to have one country pay such a large proportion of the UN’s peacekeeping bill. UN peacekeeping missions are first and foremost political instruments. As such, they require widespread political support at the Security Council and beyond. This would be more likely if more countries had a larger financial stake in the enterprise. However, the reapportioned rates to make that happen should not be decided in a unilateral and arbitrary fashion. They need to be negotiated multilaterally at the UN. Calls have recently been made for US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley to make a push on precisely this issue in her final months at the UN.

Conclusion

By not paying its assessed contributions in full and on time, the US is undermining UN peacekeeping in several ways. First, it weakens the credibility of Ambassador Haley’s claims that she wants to be a champion of more effective missions in the field and instead suggests that cutting budgets was her prime directive. Second, US arrears have reached the stage where they’re having negative impacts on mission effectiveness in the field. One recent example is Rwanda, which had to withdraw a planned rotation of one of its troop contingents to the UN Mission in Central African Republic (MINUSCA) because it had not received sufficient reimbursement. Rwanda is one of the UN’s top contributors of peacekeepers and MINUSCA is already short-staffed and currently dealing with high levels of violence against civilians and attacks on peacekeepers. Other major contributing countries are also feeling the pressure of a big delay in reimbursements, some waiting nearly a year for payment. Third, the US failure to pay its bills undermines the system of collective commitment on which UN peacekeeping is based. It sends the signal that a member state can break the established rules and get away with it. How long will it be before other states adopt a similar approach and set their own unilateral rates for what they are willing to pay and when? The UN’s peacekeepers deserve better.

Paul D. Williams is Associate Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University. @PDWilliamsGWU.