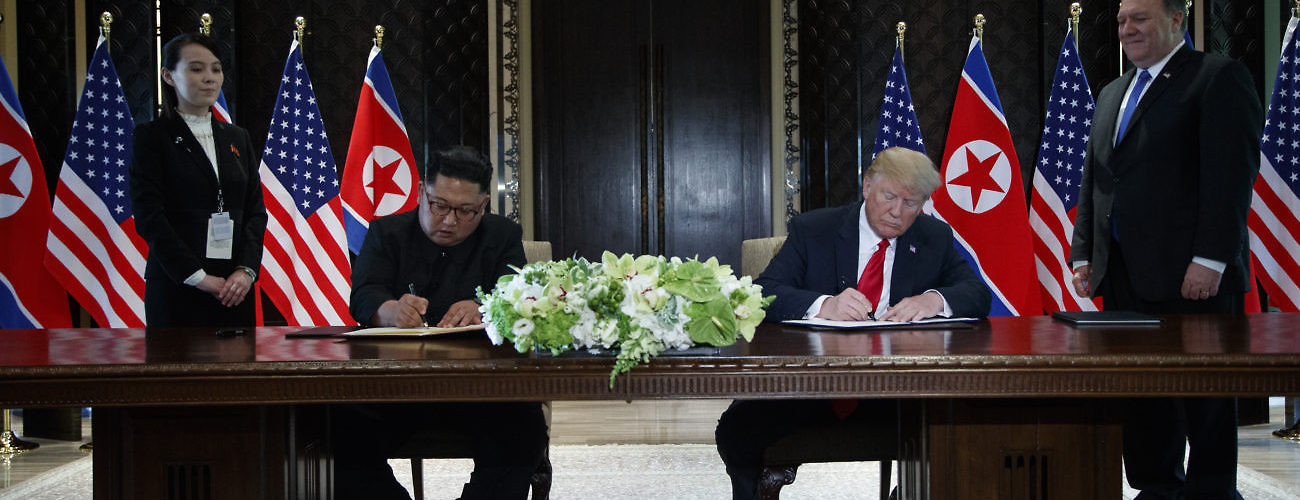

US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un participate in a signing ceremony during a meeting on June 12, 2018, in Singapore. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

The Singapore Summit between the leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Kim Jong-un, and US President Donald Trump—preceded by an historic border crossing and sit-downs with South Korean President Moon Jae-in, and meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping—is a tremendous moment by any measure. Almost exactly 55 years after the Korean Armistice Agreement, the prospect of a formal end to the Korean War and significantly thawed relations on the Korean Peninsula seems possible. Just a few months ago, North Korea and US were threatening each other with war.

Positive signs aside, much of the statement signed after the summit hinges on the vague commitment of North Korea to “work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” Outside of what this statement actually means, given the stakes for international peace and security, a closer look at some history and facts illuminate the context of Kim Jong-un’s commitment and lessons for how denuclearization could possibly be achieved.

1. Only four countries have voluntarily given up their nuclear weapons

Since the invention of nuclear weapons, only four countries have given them up: Belarus, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and South Africa.

The first three countries inherited thousands of nuclear weapons from the former Soviet Union and later agreed to give them up to Russia or destroy them, and to not pursue such arms thereafter. Although their decision was voluntary, there were concerns at the time that the countries were unable to handle the weapons properly.

Beginning in the 1970s, South Africa developed its own weapons as a countermeasure to the policies of the Soviet Union in Africa. According to F.W. de Klerk, that rationale “fell away” in 1989 with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the “nature of [the] threats” facing South Africa fundamentally changed. This fact, de Klerk’s opposition to nuclear weapons as a matter of principle, and a desire to have Africa be a nuclear-weapon-free continent, led him to order the dismantling of the country’s nuclear arsenal.

2. Failed denuclearization agreements on the Korean Peninsula have a long history

Since the Singapore Summit, many have pointed out the long history of negotiations on denuclearization with North Korea. Kim Il-sung, the father of the DPRK, signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear (NPT) Weapons in 1985. After some concern that the North’s nuclear intentions might not be peaceful, North and South Korea signed the Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula in 1992. The brief declaration contained clear commitments—far stronger than the Singapore Summit statement—that the two countries “shall not test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons”; “shall use nuclear energy solely for peaceful purposes”; and “shall not to possess facilities for nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment.” These commitments were later all violated.

In 1994, the US and North Korea negotiated a framework agreement for the freezing and eventual discontinuation of the country’s nuclear program. By 2002 though, several rounds of sanctions had been applied over North Korea’s transfer of missile parts to other countries. Kim Jong-il kicked out all international inspectors by the end of 2002, and by 2003 officially withdrew from the NPT.

A sticking point for North Korea over many years has been the joint US-South Korea military exercises. The exercises have been a regular reminder to the North that the US and South Korea are firm allies and have superior military strength. They have even been used as a bargaining chip in getting North Korea to comply with agreements, as in 1994 when the US and South Korea said military exercises would continue unless the North allowed inspections of its nuclear facilities. For its part, North Korea has regularly expressed its strong displeasure with the practice, e.g., by describing the drills as a “dangerous military scheme.” Thus, the announcement that the US will halt the exercises is meaningful to the North Korean government, though there is a great deal of uncertainty as to how it will change their actions, if at all.

3. Talking has a long history

The recent meetings between Kim Jong-un and his counterparts in South Korea and China are all positive developments, particularly in light of the stall in relations in recent years. It is also important, however, to keep these meetings in the larger context of other attempts, perhaps most notably the Six Party Talks that began in 2003. These talks brought together North Korea, China, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the United States, with the aim of negotiating an end to North Korea’s nuclear program. Although they participated in the talks, over the years that they were held North Korea conducted periodic nuclear tests and built new reactors. Ultimately, the talks stalled after North Korea ceased participating in them and revealed their plutonium producing efforts.

4. North Korea has stated its desire to denuclearize before

Despite withdrawing from the NPT, testing missiles, and sharing technology over many decades, North Korea has frequently expressed the desire to denuclearize. The late Kim Jong-il—on more than one occasion—indicated this intent, saying at one point that North Korea “will commit itself to the denuclearization of the North Korean peninsula, and hopes to co-exist peacefully with other involved parties.” A related point, especially in the aftermath of the Singapore Summit, is that North Korea agreed—but only in principle—to abandon its nuclear program and rejoin the NPT as part of a September 2005 pact.

Even in an instance where North Korea followed through on some of its stated desires—the shuttering of the nuclear facility in Yongbyon—they reopened the facility and made it fully operational.

The uniqueness of the North Korean situation makes the road towards any denuclearization long and complex. South Africa had nuclear weapons and gave them up, but they did not have the winding history of negotiations and distrust, or the experience of a devastating civil war exacerbated by foreign involvement. The former Soviet Republics had nuclear weapons and agreed to give them up, but they were facing a host of challenges to establishing themselves as independent nations and could be persuaded. The experience of countries who abandoned their development of nuclear weapons is likely the most telling, in particular that of Iran, where the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action required years of intense negotiations, gained the support of six major countries, had persuasive verification measures, and was still ultimately abandoned.

Samir Ashraf is editor of the Global Observatory.