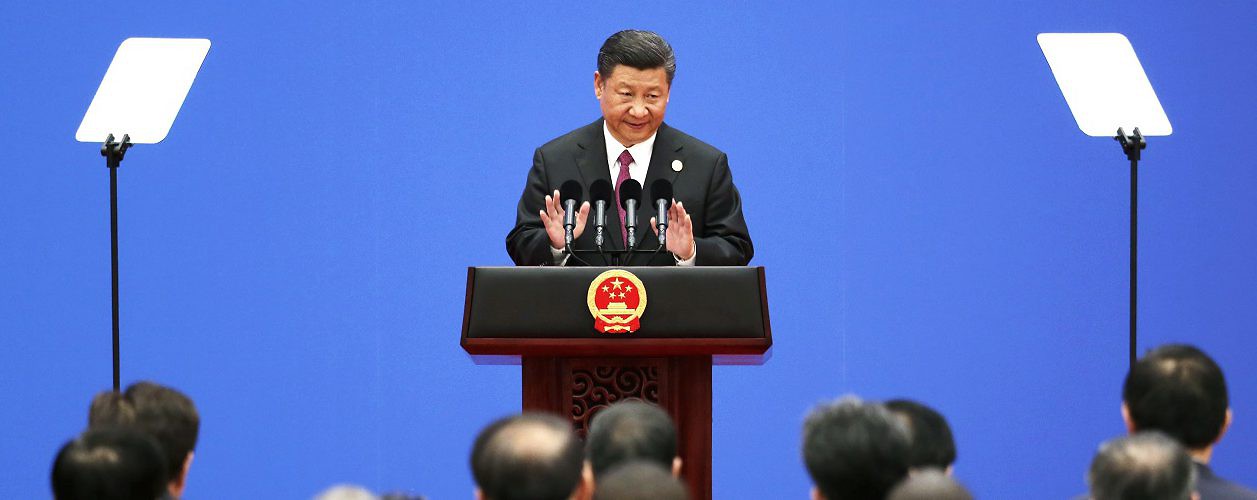

Chinese President Xi Jinping addresses media at the Belt and Road Forum. Beijing, China, May 15, 2017 (Jason Lee/Associated Press)

In May, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave opening remarks to a two-day international forum designed to demystify and attract support for Beijing’s “Belt and Road Initiative.” This estimated $1 trillion investment campaign aims to create extensive new infrastructure and intergovernmental partnerships to deepen global trade in Chinese goods and services and provide China with access to energy and other resources.

The stated intention of One Belt, One Road, as it is also known, is to expand trade and transportation infrastructure with countries on China’s western border under the rubric of reviving the “ancient Silk Road”—a hazy, but evocative reference to the centuries-old network of trade routes that reached into the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa—and expanding it to the Middle East and Europe, while simultaneously building a new “Maritime Silk Road” in Southeast Asia.

Beyond this, Belt and Road will, Xi says, create a “road for peace” and a spirit of “win-win cooperation” with partners across large swaths of Asia, Europe, and Africa. China’s leaders seek to present an ostensibly economic and strategic vision—and one that serves Chinese interests first and foremost—as a much larger normative project to advance “friendship, shared development, peace, harmony and a better future” for all involved.

The full realization of Belt and Road’s concrete-and-steel-based ambitions faces untold challenges in terms of coordinating logistics; attracting ongoing funding; and managing environmental, cultural heritage, and other competing concerns. But Xi’s utopian declarations on peace and security invite even more skepticism than Belt and Road’s economic projections. China’s positioning itself as a new guarantor of regional and international stability fails to address the enormous and very complicated challenges that lie ahead, as well as the potential that its attempts at peacemaking may in fact lead to further destabilization in many areas.

Talk of forthcoming peace and harmony may thus be no more than a smokescreen to counter perceptions that China’s attempted mass reorganization of national and regional economies seeks to secure its global dominance. (Concerns have even been raised that Beijing might increasingly use its Belt and Road-linked infrastructure to its direct military advantage, echoing its buildup at Pakistan’s port of Gwadar, for example.) The consistent tension between China and many of its most economically dependent Asian neighbors, meanwhile, already contradicts the notion that heightened trade and investment inherently lead to peace.

There is, moreover, a tendency to put the cart before the horse where pronouncements about Belt and Road outcomes are concerned. In May, Xi told potential partners that, “the ancient silk routes thrived in times of peace, but lost vigor in times of war.” This was a conveniently rosy reading of the historical record, yet it ignored the extent to which China’s military conquests were critical to the Silk Road’s establishment and maintenance. This was most notable in the Tang Dynasty’s 7th century conquest of nomadic western powers, which helped it regain control of, and expand, what were then long-degraded trading routes.

Talk of a revived and pacifying Silk Road similarly elides how much Chinese intervention will be necessary to shepherd through economic activity in areas plagued by violence and instability. As former Indian National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon notes: “Whether the promise of billions of dollars of investment and the reordering of production networks on a regional basis will help to stabilize these areas is moot, unless we also address issues of security for investments, projects and infrastructure.”

Rather than its inevitable end product, peace should instead be considered a precondition for achieving progress on the Belt and Road vision. There is already considerable evidence of China’s foreign policy decision-makers seeking to prime future areas of economic interest for the campaign by ensuring their peace and security. This includes complex interventions in countries in Southeast and Central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East. (Beijing has also increasingly sought protections of Chinese investments and citizens deployed across the world in recent years.)

Unfortunately in terms of upholding Xi’s promises, the results of these actions often bode poorly for long-term amity. Continued Chinese military consolidation in the South China Sea, for example, shows that China’s leaders will forcefully pursue their strategic and economic interests where it remains possible.

Conquest-style tactics are now more difficult to pursue on land, however, where questions of sovereignty, and the repercussions of violating it, are more cut and dried. But rather than abandon its aims, Beijing has increasingly adopted a more outwardly benevolent focus on peacemaking. Yet this may prove difficult to achieve for a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that has long sworn off the type of interventionism practiced by the likes of the United States government, and which also traditionally eschews the third-party mediation of conflicts typical of European administrations.

China continues to lack substantive experience with, and appears reticent to fully engage in, intervention in other countries’ domestic matters. Coupled with the narrow focus on national outcomes at the heart of the Belt and Road initiative, the end result of the peacemaking China will need to engage in may be its policymakers pursuing a series of poorly planned and/or short-term actions with long-term negative ramifications for many parties. This is clear from an analysis of a handful of Belt and Road-associated peace and security efforts already underway.

A Road for Peace?

Among the most challenging peacemaking efforts China is undertaking are in Myanmar. As a recent United States Institute of Peace report notes, Beijing has played a significant role in facilitating and even mediating negotiations between the government in Naypyidaw and ethnic armed groups on its own border. Perhaps its largest contribution was enticing three of these groups to participate in last year’s landmark Union Peace Conference, organized by Myanmar’s then newly installed (de facto) leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, who hopes to end her country’s long-running civil conflict. Also last year, China and Myanmar established a bilateral consultation mechanism between the foreign and defense ministries in both of their countries to monitor and manage conflict along their border.

Though it might otherwise be considered an end in itself, a more stable Myanmar would help smooth the way for China’s considerable Belt and Road-linked economic plans in the country. These include new oil and gas infrastructure that will build on a long-delayed pipeline which opened in April this year, and an associated special economic zone and deep-sea port at Kyaukphyu on the Bay of Bengal.

There have, indeed, already been explicit links drawn between peace and economic development by some of the China-backed Burmese groups: In February this year, a summit of seven of these drafted a document calling for a Beijing-mediated peace process, and also declared support for Belt and Road with “security guarantees for Chinese projects in armed group areas.”

While this seems to adequately serve Chinese interests, the seven groups have in turn pulled support for the Suu Kyi-led peace process, which, as a more comprehensive and localized affair, retains a better chance of achieving long-term stability. Were China to complicate matters by breaking away from this, it would in turn leave progress more subject to the whims of Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, which retains significant influence on Burmese politics and continues to engage many of the armed groups in battle. This is even as it, too, pledges support for the formal peace process.

China’s attempted stabilization is no less fraught with danger in Belt and Road’s Central Asian heartland, where Afghanistan’s largely Taliban-derived violence is a perpetual concern. A bombing in May that killed more than 150 people was the deadliest single extremist attack in the country since the US invasion more than 16 years ago, and attests to the slim prospects of security being achieved any time soon.

Yet the poor chances of success have not stopped Chinese negotiators participating in both the Quadrilateral Coordination Group peace negotiations (with the US, Pakistan, and Afghanistan) and a newer Russian-led effort that also involves India, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan itself. Taliban officials have also traveled to Beijing to speak with Chinese officials, while Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi in June announced a new program of “shuttle diplomacy” between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

More surprisingly, Chinese troops are also reported to be operating in Afghan territory, undertaking counterterrorism patrols with local forces. This raises the risk of future entanglements, including even with the US, whose politicians and military leaders have long struggled to extricate themselves from the conflict and are again set to send in more troops.

Beijing’s motivations in Afghanistan include the desire to manage threats to the CCP’s control of the Xinjiang region coming from militant Islamic groups. But stability on both sides of the border will be critical to the long-term success of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor—a system of trade, energy, and other economic infrastructure that aligns, and ultimately connects, with the larger Belt and Road.

To subvert Xi’s own language, his government’s interventions in Afghanistan could ultimately be a win-win, whereby pacification of the Afghan population and China’s own Uighurs would smooth the progress for new infrastructure projects, whose pursuit would in turn extend Beijing’s regional control. On the other hand, the remaining countries engaged in Afghanistan’s peace process retain their own, often conflicting motivations for doing so—Pakistan wants a political normalization of the closely aligned Taliban, for example, while India wants the exact opposite. This, again, creates a situation filled with potential exacerbation of tensions, which might ultimately jeopardize Belt and Road investments and Beijing’s long-stated desire to avoid foreign policy quagmires.

On a somewhat related note, India boycotted the May forum, largely because of plans for Chinese investments in territory New Delhi considers its own. Belt and Road has thus been subsumed into larger and periodically resurfacing tensions between India and China, including the current border dispute that also takes in Bhutan.

Further afield, China has sought an end to the bloody war in South Sudan, which, though not an official Belt and Road country, connects to the broader framework through a rail link to Kenya. The China National Petroleum Corporation is, moreover, the biggest investor in the South Sudanese oil industry, which increases Beijing’s motivations for local stability.

To this end, China has participated in the South Sudan-focused “IGAD-Plus” peace talks and is simultaneously contributing its largest ever frontline peacekeeping contingent to the UN mission in the country (as of May this year, this was the fifth-largest national contribution). This has, however, been a chastening experience, with Chinese troops suffering several fatalities and also facing accusations of failing to protect South Sudanese civilians as tasked.

Some UN insiders have told me that the ineffectual commitment of Chinese peacekeepers to their tasks was possibly a result of troops not wanting to upset local South Sudanese powerbrokers, which could have in turn had repercussions for wider Chinese interests in the country.

China’s action in South Sudan certainly falls well short of the sort of long-term, intensive effort required to make a breakthrough on the country’s peace and security.This particular case study would therefore seem to illustrate the ongoing tension between Beijing’s long-established foreign policy norms of not intervening in others’ domestic political affairs and its emerging desire to take a more assertive stance in defense of its interests. Worrying in terms of its pacification efforts, it suggests an ineffective compromise between the two will inevitably be sought. In the case of its alleged arming of some of the conflict’s combatants, there is evidence Beijing may go even further, and directly support those parties it believes can deliver it a positive outcome, irrespective of the ramifications for peace and security.

Elsewhere in Africa, tiny Djibouti is benefiting from Belt and Road’s construction of a new free trade area, which its backers claim is the continent’s largest. While not overly conflict-riven itself, Djibouti also hosts a Chinese naval and military facility, to which Beijing first deployed troops in June.

In March, General Thomas Waldhauser—the head of the US Africa Command—described the Djibouti facility as China’s first overseas base. This would seem to validate the earlier mentioned fears that Belt and Road-linked infrastructure in places such as Pakistan’s port of Gwadar will serve Chinese military aims. It might also ultimately contribute to an escalation of tensions with and among regional parties, including allies of China’s rival power, the US.

For its part, Beijing rejects the assertion the Djibouti base will be used to project force abroad, as with American facilities of this nature. In a statement forwarded to The New York Times, Chinese defense officials said the Djibouti base did not demonstrate an “arms race or military expansion,” while a 2016 Global Times article claims it is all about supporting Chinese peacekeeping in Africa, as well as combating Horn of Africa piracy. Where these activities are linked to pacification and/or asset protection efforts, including in relation to Belt and Road, it would still carry the same risks of complication as seen in the likes of Myanmar, Afghanistan, and South Sudan.

The Middle East, finally, features heavily in Belt and Road considerations. Here, too, China has sought limited, albeit complicated entanglements of a type it would have previously stayed well away from. This includes reportedly wanting to play an active role in the Israel-Palestine peace process, which has long consumed an incommensurate amount of foreign, and even domestic, policy energy in the US and other countries.

Beijing has already intervened in Syria’s intractable civil war, sending military advisers to assist President Bashar al-Assad’s forces and condoning Russia’s more forceful intervention in the country, as well as aiding its gridlock of international action on the conflict through the UN Security Council.

Just as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Syrian actions are at least partly designed to secure Moscow’s long-term strategic interests in the Middle East (such as continued access to the Mediterranean port of Tartus), Xi’s more measured support for Assad could give China an influence in reconnecting Syria to the world if and when the regime secures victory over Syrian rebels; indeed, Beijing has already drawn explicit links from Syria’s recovery to Belt and Road, including through a recent humanitarian commitment.

The long-term costs to the Syrian people of intentionally prolonging the conflict, and of attempting to preserve Assad’s hold on power, do not appear to figure into the equation.

A Limited Peace?

Xi’s vision for Belt and Road seems to extend to a new Pax Sinica that will extend Chinese largesse across continents and hemispheres. It is thus something of a global recalibration of the neo-traditionalist view—advanced by the CCP and the likes of academic David Kang—that China has a largely benevolent, pacifying influence when it is dominant. There is a necessary qualification to this, however: that there are great challenges, and risks, that come from China seeking to regain historical strength or extend itself into new areas.

In the case of Belt and Road, these new areas, as the Australian National University’s Hugh White puts it, at least extend to securing a “position at the centre of the global supply and manufacturing networks”—at the most, they seek to globalize China’s well-established hegemony in East Asia. The challenges and risks are in turn multiplied by the tensions between Beijing’s ambitious economic and foreign policy goals and its lingering inexperience with, and aversion to, many of the activities required to achieve them.

Despite Xi’s celebrating the promise of some forthcoming commercial peace set to arise from its Belt and Road Initiative, he and CCP policymakers clearly recognize that they must directly intervene in the here and now if they are to successfully achieve their ambition. While the use of coercive force might otherwise be the preference, attempts at a more benign-seeming peacemaking are often the only alternative.

Yet none of the endeavors Beijing has embarked upon in this vein are easy, or without serious potential repercussions for China or other countries involved. Diplomats and military planners have tried, failed, and often rued the repercussions of seeking to find a satisfactory end to Syria’s war for more than six years; they have been intractably engaged with the Afghan conflict’s current incarnation for more than 15; and Myanmar’s battle with ethnic armed groups is, at more than 60 years, considered the world’s longest-running civil war. This is to say nothing of the potential pitfalls of any level of engagement with Israel-Palestine.

In diving into global peacemaking efforts as a result of Belt and Road, Beijing may increasingly find itself out of its depth. It may in turn commit to half-measures only intended to achieve a level of security necessary to shepherd through a set level of investment or to avoid any continued erosion of what remains of its once steadfast commitment to non-interventionism. The continued deleterious situation in South Sudan—a country that was itself created from an incomplete international peacemaking attempt in the first decade of this millennium, and where China now faces criticism over its superficial levels of engagement—should be warning enough of the need to avoid this.

This article originally appeared on ChinaFile.