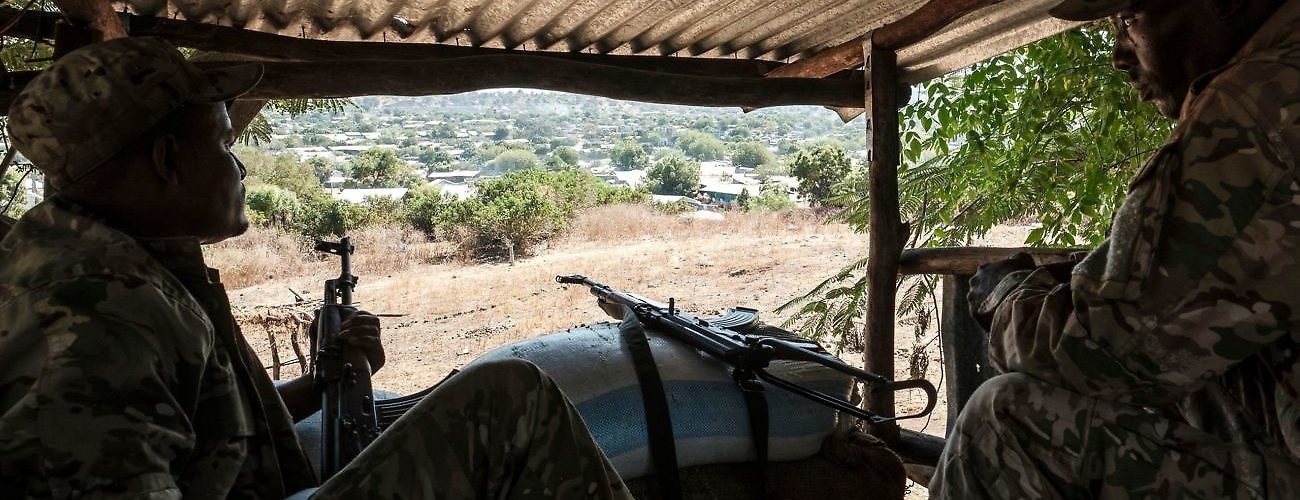

Members of the Amhara Special Forces keep guard at the Northern Command of the Ethiopian Army in Dansha, Ethiopia, on November 25, 2020. (EDUARDO SOTERAS/AFP via Getty Images)

Since the resignation of Hailemariam Desalegn and the rise of Abiy Ahmed to power in 2018—initially as the leader of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front and later of the Prosperity Party (PP)—regional special forces have been involved in at least three major conflicts in Ethiopia. These conflicts demonstrate that special forces have engaged in a pattern of instigating violence that poses grave danger to the peace and security of Ethiopia and could, in fact, derail the democratic process.

Constitutionally, peace and security are a shared responsibility between the federal and regional state governments. The federal government is entrusted with establishing and administering the “national defence and public security forces as well as a federal police force,” as Article 51 of the Ethiopian Constitution stipulates. On the flip side, regional states are endowed with the power “[t]o establish and administer a state police force, and to maintain public order and peace within the State” based on Article 52. As a blueprint, such a division of powers might appear clear and well defined, and even a basis for stability. But Ethiopia’s recent history has been an arduous path with numerous bumps along the way, exacerbated by the existence of regional state special police—Liyu hayil in Amharic–as well as local police forces.

Recent Conflicts in Somali, Amhara, and Tigray Regional States

The peace and security arrangement between federal and regional states has allowed special forces to instigate conflicts in unique ways. Incidences in Somali and Amhara regions, and the current conflict in the Tigray region, demonstrate the magnitude of the problem.

In Somali, the former president Abdi Mohamed Omar “Iley” was well-known for his tyrannical and abusive measures, crimes, and mass atrocities against secessionist rebels. He also got involved in the Somali-Oromo conflict that emerged. Building a well-armed special force, he went on to advance violence in the Somali Region, where, as Tobias Hagmann put it, “[t]he [special forces] eventually took control of almost all security functions once held by the regular police, the custodial police, and the federal military.” This eventually forced Prime Minister Abiy to intervene with federal forces and arrest Abdi Iley in August 2018.

In Amhara, the commander-in-chief of the Regional Special Force, Brigadier General Asaminew Tsige, decided to use force to carry out a coordinated assassination of the top officials of the region, including Chief Administrator Ambachew Mekonnen and his advisor Ezez Wassie in June 2019. This led to the assassination of General Seare Mekonnen, chief of staff of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), and Gezai Abera, a retired senior general, in Addis Ababa. Many had previously warned of the possible threat such special forces might pose, and the attack forced the federal army to intervene and normalize the situation after killing Brigadier General Tsige and some of his followers.

And finally is the current situation in the Tigray Region. In response to the November 4 attack by forces of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the federal government used its federal power to mobilize the ENDF and other forces. A mechanized and drone-assisted war led to the retreat of the TPLF’s special forces and militias from large areas of the region, with the swift capture of Mekelle, the capital. The federal government argues that this is a straightforward case of law enforcement and doing what is necessary to maintain peace and security, while the leaders of the ousted Tigray regional government claim that they are fighting for “self-determination.” In addition to the concerning confirmation by Amnesty International of the massacre of hundreds of people in Mai Kadra, the fact is if the TPLF did not have a 250,000 strong contingent of special forces and militias, they would not have taken action against a federal military base. To complicate the situation further, special forces from other regions, including from Amhara and Afar, are fighting in support of the ENDF and to advance their own agendas.

These three cases reveal both the complexity of and the causes of concern for long-term peace and security in Ethiopia. They show how the authority given to both federal and regional forces—coupled with a lack of accountability— creates space for political, military, and socio-cultural differences between the regional and federal to translate into violent conflict.

A Way Forward

Besides being unconstitutional, leaving high-level security matters to the regional states and their special forces would not appear to be ideal. On the assumption that ethnic federalism continues as an overarching political philosophy in the foreseeable future, the following suggestions might assist in addressing the increasing number of small or large scale clashes involving special forces in Ethiopia.

The first is to establish a unitary federal peace and security regime. This involves dropping the idea of regional special forces and restricting the regions to having a regional police force. High-threat security matters can then be dealt with by the federal army, which would base itself in each of the regional states. This wouldn’t require a constitutional amendment, but rather a parliamentary by-law that mandates the abolishment of the regional special forces.

The second is to form a federal-regional joint force. This involves solidifying the federal government’s oversight powers with respect to the regional special forces. Forming a joint central command for all special forces, with authority shared between the federal and regional state, would bring its own management difficulties. Nevertheless, this approach could serve at least for a transitional period that would lead to the full integration of the special forces into the ENDF.

Though disarming the special forces and integrating them into the national army is necessary, it will also be difficult. Careful planning, consultation, diplomatic persuasion, and a well-designed and workable integration program are needed for this effort to not lead to further political chaos.

With the recent incidences in the Amhara and Somali regions, and the gravity of the current situation in Tigray, both federal and regional government leaders should prioritize mitigating the harm caused by special forces and the franchising of security policy in order to maintain law and order in Ethiopia. Political leaders should explore the possibilities for the establishment of an alternative peace and security institutional regime, and engage in an inclusive security-focused dialogue to escape from the vicious cycle of “states of emergency” in response to each threat posed by regional special forces. These approaches won’t be a panacea for all the political uncertainties and the contagion of conflicts in Ethiopia, but might form part of the pathway towards constitutionalism, reconciliation, and a peacebuilding process.

Bereket Tsegay holds a PhD in Development Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London and his research interests include conflict analysis, climate change, social security, policy, and governance analysis. He tweets @bereket_tsegay.