Workers construct the Gbarnga Peace Hub, funded with assistance from the UN Peacebuilding Support Office. Monrovia, Liberia, April 28, 2012 (Emmanuel Tobey/UN Photo)

Peacebuilding broadly involves a range of measures targeted at reducing the risk of countries lapsing or relapsing into violent conflict by strengthening national capacities and institutions at all levels of conflict management.

But while peacebuilding activities are important and indeed necessary, there is no accurate measure of the size of global peacebuilding expenditures. There is, in fact, no internationalized or standardized definition for what constitutes definitive peacebuilding actions. As a consequence, there are no clear comparable country specific data on peacebuilding expenditures, nor clear understanding where resources are being committed, whether simply at the nation state level or at the programmatic level.

This highlights an obvious problem: Without a clear picture of the annually recurrent expenditures and resources committed to peacebuilding—who is spending where and on what—it is not possible to systematically assess the efficacy and efficiency of peacebuilding programs. Consequently, it is hard to gauge the cost-effectiveness of peacebuilding—the degree to which the economic benefits arising from greater levels of peacefulness outweigh the monetary costs engendered by peacebuilding expenditure.

Without the necessary data, it is very difficult for governments, bilateral donors, international financial institutions, and United Nations agencies to determine peacebuilding needs. Equally, without an accurate global breakdown of the direction of peacebuilding resources, various research and advocacy efforts aimed at understanding what works or doesn’t in peacebuilding are hampered.

Peacebuilding Expenditure

At a time when development and humanitarian aid to the poorest countries is in decline, the need to understand and invest in the most cost-effective ways to build peace is more crucial than ever. But peacebuilding remains a relatively overlooked dimension of official development assistance (ODA).

The latest available OECD data shows that conflict-affected countries do not represent the main beneficiaries of ODA. In 2013, these countries received slightly more than 24% of total ODA from OECD members, or $41 billion. Out of this total, only 16% was allocated for peacebuilding activities.

Figure 1: Peacebuilding Expenditure as Percentage of ODA in 31 Conflict-Affected Countries, 2013

Of the $41 billion of ODA directed to conflict-affected countries in 2013, only 16% was peacebuilding-related.

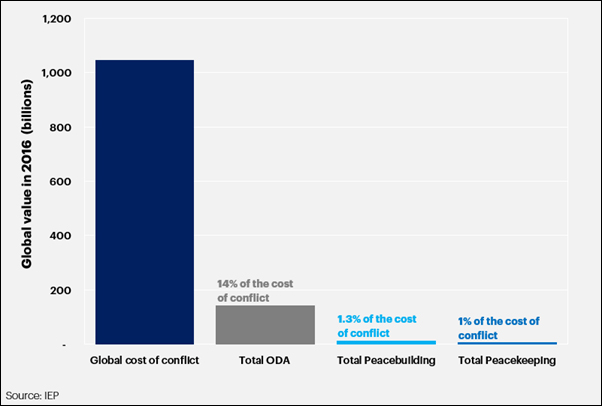

While the global economic losses from conflict in 2016 reached a staggering $1.04 trillion, just $21.8 billion was spent on peacekeeping and peacebuilding activities combined during that year. This means that the financial resources devoted to avert violence and consolidate peace constituted a mere 2% of the total cost of conflict.

At such comparatively low levels, the potential impact of peacebuilding activities is hindered by the destructive effect of violence. This does not, however, mean that peacebuilding investments are futile, but rather that their levels need to be more aligned with the significantly higher cost of conflict.

Figure 2: Economic Losses from Conflict Versus Expenditure on ODA, Peacebuilding, and Peacekeeping, 2016

In 2016, expenditure on consolidating peace represented just 2% of the total economic losses from conflict.

A Cost-Effectiveness Model

The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) has built a global model of peacebuilding cost-effectiveness that shows increased funding for peacebuilding would be hugely beneficial, not only to peacebuilding outcomes but in terms of the potential economic returns to the global economy.

Estimating a unit cost of peacebuilding is difficult, as there have been very few examples of successful long-term peacebuilding strategies in the last 25 years. The IEP model uses Rwanda over the period of 1995 to 2015 as an example of “successful” peacebuilding, and thus as the basis for the unit cost of peacebuilding for all countries in the model. In other words, the model assumes that the level of peacebuilding funding per capita required to achieve the peace scenario is the same as for Rwanda over the period 1995-2015. This allows IEP to estimate the current peacebuilding shortfall for each of the 31 conflict-affected countries included in the model.

The cost-effectiveness ratio for each country is the ratio of the required increase in per capita peacebuilding to reach the same level as Rwanda, divided by the estimated peace dividend for that country. For the 31 conflict-affected countries as whole, the average of this ratio is 1:16, meaning that for every additional dollar spent on peacebuilding to reach the same levels of Rwanda, the future cost of conflict would be reduced by $16. Projected forward 10 years from now, this would save $2.94 trillion in direct and indirect losses from conflict.

Achieving this outcome would, however, require an approximate doubling of peacebuilding expenditure in the 31 most fragile and conflict-affected nations of the world. Of course, this does not preclude other important factors for peacebuilding success such as the external influence of other states or the role of political elites, but rather establishes a working framework for resources required for effective peacebuilding activities.

Building an Evidence Base

At the global level, the IEP model illustrates that peacebuilding can be significantly cost-effective. However, this does not reveal anything about which types of peacebuilding initiatives are the most suited to accomplish the end goal.

The data generated by IEP in its first phase of research provides an extensive set of further options to model the statistical link between peacebuilding and conflict onset, or lack thereof. Consequently, IEP’s methodology can be used to calculate and estimate the future peacebuilding needs that exist in particular countries.

Seeking cost-effective and impactful peacebuilding strategies is a key element to sustainable progress in post-conflict and conflict-affected societies. Working under the premise that peacebuilding is a necessary global public good, the more nations invest in peacebuilding, the more rewards that will flow.

The increased availability of data on cross-country peacebuilding best practices—as is being sought by IEP—would allow international donors to adjust peacebuilding needs more closely to the levels of damage incurred by conflict and violence more generally.

Following the adoption of “sustaining peace” agenda by UN member states, peacebuilding has been placed firmly on the global agenda. The need to better understand the outcomes and best practice is critical. IEP’s methodology is a first step in this direction.

José Luengo-Cabrera is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). Tessa Butler is a Communications and Outreach Specialist at IEP.