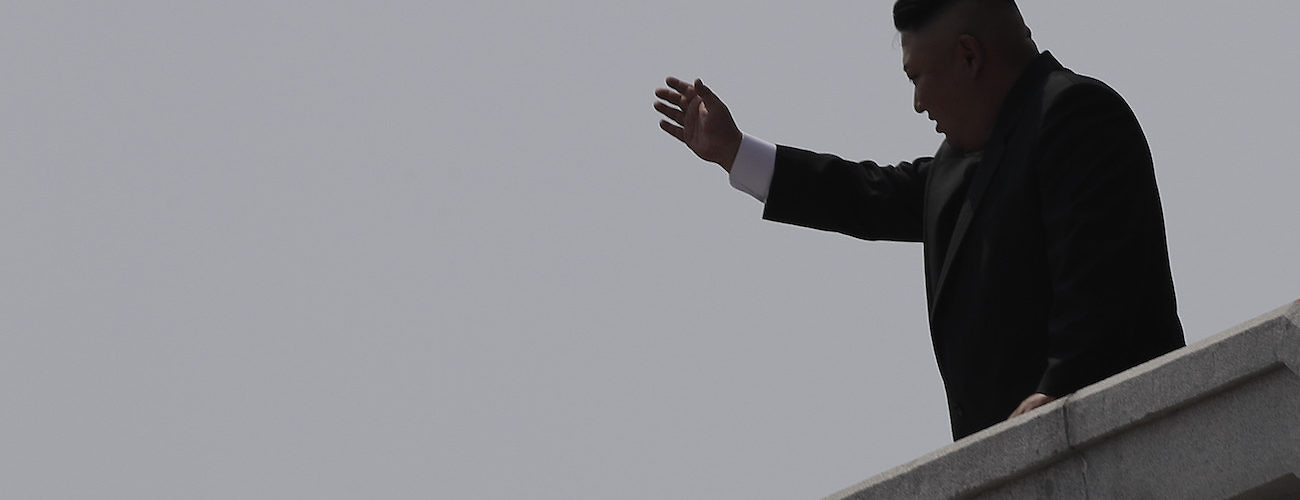

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un waves during a military parade in Pyongyang, North Korea, April 15, 2017. (Wong Maye-E/Associated Press)

In the wake of a multiple missile salvo that once again heightened tensions on the Korean peninsula, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on March 8 proposed a new approach to address the North Korean threat. On the fringes of the National People’s Congress annual session, Wang told journalists that, “to defuse the looming crisis on the peninsula, China proposes that, as a first step, the DPRK [North Korea] suspend its missile and nuclear activities in exchange for a halt of the large-scale US-ROK [South Korea] exercises.” Both the United States and South Korean ambassadors to the United Nations at first rejected the idea, the latter claiming that, “this is just trying to link the unlinkable.” Is this really the case?

The fact that the proposal came a few days after the US delivered the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-ballistic missile system to South Korea—which Beijing has long opposed—and ahead of US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s visit to China, was no coincidence. Beijing is eager to show the new American administration its centrality in dealing with North Korea, while pointing out the negative consequences of what it considers as undue military pressure by the US and South Korea on the peninsula. Whatever the motive behind Wang’s proposal, it is worth exploring given the current deadlock and continued testing—12 missiles have been launched so far in 2017, including three in May alone.

If force is given priority over diplomacy in regard to North Korea, US President Donald Trump would repeat the mistake of his predecessors Barack Obama and George W. Bush. The alternative of a reduction of military pressure would instead see the leadership in Pyongyang question the relevance of its own policies based on this same military power. Perhaps most importantly, such a deal would ensure Beijing’s continued engagement on the North Korean issue, while the deterrent power of the US alliances with South Korea and Japan would remain strong enough to guarantee the security of these key American allies.

North Korea as a Militarized State

To understand why this “two-way suspension deal” is promising, it is useful to conceptualize North Korea’s foreign and security policy decision-making. Resorting to abstraction is not usually the ideal starting point for a policy-oriented analysis, but the opacity of the regime in Pyongyang leaves little other choice.

The country’s policy in these areas is typical of militarized states, in which military institutions possesses a significant influence on the leadership. As articulated by Richard K. Betts in Soldiers, States, and Cold War Crises, these institutions in turn possess strong biases. The most pronounced is the tendency to conduct analysis based on worst case scenarios. This is because it is the military’s duty to prepare for any contingencies in the event that diplomacy fails to settle disputes peacefully.

Military planners tend to be perpetually dissatisfied with the security situation, to seek to accumulate as much power as possible, and to provide advice to government leaders based on pure military logic and relative capabilities. It does not mean that diplomatic and other factors are completely dismissed, or that the military planners are warmongers. Rather, it implies that for these institutions, military assets and postures speak more clearly than political statements and diplomatic agreements.

In militarized states, the perception of the political leadership toward the international environment and its subsequent decision-making process is distorted by the institutional biases of the military. Security policy has a tendency to be unilateral, biased against international cooperation, and primarily based on power.

North Korea has relied heavily on such military power for its protection—the nuclear and missile programs are the clearest expressions of this. Due to skepticism of outside actors, Pyongyang has also been reluctant to depend on Russia and/or China for its security, although it has at times benefited from their weaponry, technical assistance, and diplomatic support. The perception Pyongyang has of its international environment and of the intentions of other countries is often described as paranoiac. Although clearly biased, it must be recognized that this view possesses roots in reality.

Lessons from Past US Policy

Thinking of North Korea as a militarized state helps explain the failure of US policies toward it since the end of the Cold War. First, economic sanctions and other coercive measures are powerless in reorienting its security policy. They are also counterproductive as they reinforce the perception held by the North Korean leadership that the US and its regional allies are intrinsically hostile. Second, security assurances are by themselves impotent. A militarized state is inherently skeptical about such guarantees, which represent nothing more than political pledges, because the leadership’s assessment is primarily based on capacities and postures related to force, which are not modified by such pledges.

In this context, a reduction of military pressure on Pyongyang is the only way to break the North Korean deadlock. The US did, in fact, adopt such an approach during the 1990s, and met with relative success. Amid suspicion about a covert nuclear weapons program, the Clinton administration moved to directly address the issue and obtained Pyongyang’s satisfaction with the Agreed Framework of October 1994. The US agreed to facilitate construction of two nuclear proliferation-proof light-water reactors and to supply heavy fuel oil to the North. In exchange, Pyongyang committed to freeze its plutonium program and to remain a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. The deal also opened the door to a normalization of economic and political relations.

A crucial factor in the success of the negotiations was the American cancellation of the US-South Korea Team Spirit exercise (the former name of the current Key Resolve program) in early 1994. The Clinton administration suspended the annual exercise in 1995 and 1996 to give diplomacy a chance. Although implementation of the Agreed Framework was strained by a series of subsequent events, notably the first test of a long-range ballistic missile by North Korea in August 1998, the two countries kept cooperating on several issues.

The framework eventually crumbled, however, after an American delegation to North Korea in October 2002 came back with certainty that the country was pursuing a highly enriched uranium program. Nevertheless, it showed that a reduction of military pressure might be the only way to open the door to a diplomatic settlement.

Reduced Military Pressure as a First Step

In line with Wang’s two-way suspension proposal, the US could slow down the deployment and rotation of military assets and personnel in South Korea, and accelerate that country’s control of armed forces in wartime. More importantly, annual joint military exercises could be scaled back and conducted farther away from North Korea’s territory. Scenarios could be revised to appear less threatening from Pyongyang’s perspective. This would radically reduce tensions and have a real impact on the North’s perception of its international environment.

These activities would not radically affect the deterrent power of the US-South Korea alliance. The degree of interoperability between the armed forces might somehow decrease, but not extensively as long as exercises are not completely canceled.

Even with the scaling down, it would still be suicidal for Pyongyang to trigger war on the Korean peninsula. South Korean armed forces are qualitatively superior and much better prepared for modern warfare than their northern counterparts. The US also maintains an overwhelming military presence in the region. Finally, Japan’s government recently reclaimed the legislative right to collective self-defense and can be expected to back, and possibly participate with US forces in, any war that occurs.

The US going along with the two-way suspension proposal would also help ensure Beijing’s engagement. China would have little choice but to pressure Pyongyang to come back to the negotiation table and show flexibility if it does not want to lose face. Due to its economic and diplomatic influence on North Korea, China remains key to dealing with the reclusive state.

The THAAD Issue

Still, China would likely ask the United States for its own reward in efforts toward solving the North Korean puzzle. It is here that THAAD enters into the picture. Beijing has voiced strong objections to the system, primarily because its long-range radar capability allows American surveillance of military activities, in particular missile tests, deep inside Chinese territory.

Both South Korea and the US have tried to reassure China that THAAD aims exclusively at tackling the North Korean threat, and that its radar would be maintained in a “terminal mode” configuration, which reportedly has a range of 600 kilometers, compared with the 2,000-3,000 kilometer range of the “forward-based mode.” Although Trump repeated the pledge during their Mar-a-Lago meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in early April, Beijing does not appear convinced—the radar can indeed be converted between modes in only a couple of hours.

For the foreseeable future, it would be difficult for the US to withdraw THAAD from South Korea, not least because it would send Seoul the wrong signal about US security commitments amid the persistent North Korean threat. Even though new South Korean President Moon Jae-in has voiced opposition to the hasty deployment of the system, several stakeholders inside the country supported the move. One way of addressing China’s suspicion would be to allow the country to monitor the configuration of the THAAD radar, for example, by permanently stationing Chinese military personnel to the relevant command and control headquarters, or through regular military inspections.

To keep China onboard, the US would also have to resist Japan’s acquisition of THAAD. Tokyo is considering introducing it to add another layer to its anti-ballistic missile defense structure. Defense Minister Inada Tomomi recently visited Guam, where THAAD is also deployed, to inquire about its potential. In the case of Japan, China’s grievances would be related to the wider geostrategic consequences of the anti-ballistic missile system, rather than the specific radar issue.

In addition to strengthening Beijing’s perception that the US and its regional allies are pursuing a policy of containment, the deployment of THAAD in Japan would jeopardize Chinese “anti-access/area-denial” strategy. This aims at undermining American military power projection, symbolized by aircraft carriers and their escorts, in order to keep the US out of the East and South China Seas and the Yellow Sea in case of conflict. Because anti-ship ballistic missiles are key assets of the anti-access/area-denial strategy’s first defense layer, which extends up to 2,000 kilometers from Chinese coasts, the introduction of THAAD by Japan would weaken China’s ability to prevent US forces from reaching the first island chain—consisting of Japan’s main islands and Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, the northern Philippines, and Borneo—on their way from naval bases in Guam, Hawaii, and the West Coast of the US.

Diplomacy over Power Politics

To be sure, the two-way suspension deal would not in and of itself halt North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs. The road toward denuclearization will be bumpy, and a great deal of diplomatic creativity will be required to ensure this happens peacefully. But the deal would reopen dialog between Washington and Pyongyang. As the latter is close to acquiring a deliverable nuclear capacity, it is critical to maintain diplomatic channels to prevent the situation getting out of control. A diplomatic deal of this nature is a necessary first step to accommodate a militarized state endowed with increasingly sophisticated capabilities, and hopefully to pave the way for a later comprehensive settlement of the North Korean issue.

The US today faces the choice between power politics and diplomacy. If it chooses the latter, reducing military pressure on North Korea is a prerequisite. If the Trump administration sticks to power politics, the best of the bad options might be to attack at the earliest stage, before North Korea acquires a fully deliverable nuclear capacity.

Dr. Lionel Fatton is Lecturer of International Relations, Webster University, Geneva; a Research Associate, CERI-Sciences Po, Paris; and a Research Collaborator, Meiji University’s Research Institute for the History of Global Arms Transfer, Tokyo.