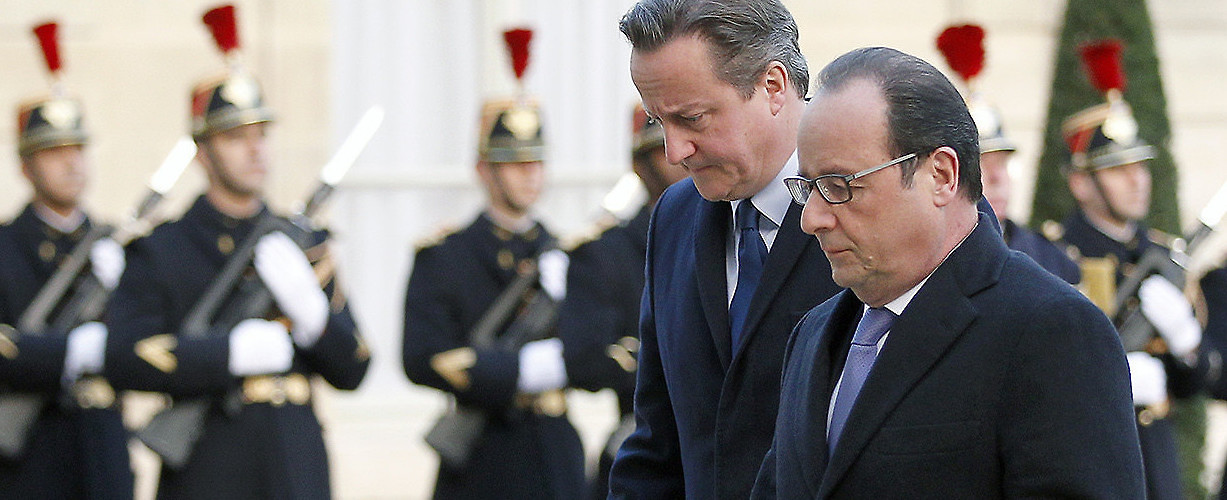

French President Francois Hollande and British Prime Minister David Cameron meet at the Elysee Presidential Palace to discuss the response to November's Paris attacks. Paris, France, November 23, 2015. (Thierry Chesnot/Getty Images)

As well as producing an outpouring of grief and increased security, November’s Paris terrorist attacks raised significant questions about European Union foreign policy. This was reflected in last week’s complicated debate in the United Kingdom on whether or not to bomb targets of Daesh [also known as ISIS] inside Syria. The UK’s eventual affirmative vote made it the only EU member to join full-scale French-led efforts against Daesh so far. What does this reveal about the level of cohesiveness in the bloc?

When France began bombing Syria earlier this year, fellow EU governments offered little support. The situation has remained broadly the same after the Paris attacks, with the notable UK exception. France appealed for direct help from London even though the domestic British debate has not previously been conducive to providing it. While the UK has long been a member of the anti-Daesh coalition in Iraq, Prime Minister David Cameron was cautious in expanding efforts into Syria. In 2013, he suffered a political blow when the House of Commons rejected a targeted air campaign against the Bashar al-Assad regime, following reports it was employing chemical weapons against opponents.

While concerns about a complicated and uncertain military involvement have persisted in light of the ongoing repercussions of the British-supported Iraq War, the Paris attacks appear to be a turning point. The 10-hour debate in the House of Commons showed that previous arguments remain prominent, though there was ultimately little doubt that members of parliament would back Cameron’s position.

In addition to the UK, France also had some measured expectations for help from Germany, even though it has long been frustrated by Berlin’s disinclination to use force in addressing conflicts. Early signs were that the German government would not go beyond providing a further presence in Mali, where French troops are also serving, and bolstering training of the Daesh-opposing Kurdish Peshmerga in Iraq. It therefore came as a welcome surprise to Paris when Berlin announced it would send a frigate to escort a French aircraft carrier in Syria, conduct surveillance over the country, and provide air-to-air refueling. Though not constituting a direct show of military strength, these are significant moves from Germany.

Also said to be considering a direct intervention are Denmark—which is mulling over expanding its current involvement in Iraq—and the Netherlands. Belgium, meanwhile, has already deployed a frigate to escort a French aircraft carrier to Syria, in a move announced a few days prior to the Paris attacks.

Support from elsewhere in the bloc has largely been lacking, however, even though France has invoked the mutual defense clause in the EU treaty, obligating member states to provide aid and assistance “by all the means in their power.” The hesitancy to join the Syrian campaign must, however, be weighed against France’s limited expectations of its EU partners. With this taken into account, the lukewarm support is unlikely to further splinter EU foreign policy, though it certainly won’t solidify it.

French President François Hollande announced he was expanding the anti-Daesh campaign into Syria from Iraq in September—the first EU country to do so. Until the Paris attacks, the French air force had struck only three times in the country. Its operational tempo and the pressure on EU partners to follow suit accelerated dramatically after the events, though it remained cognizant of the likely reluctance of many to do so.

As well as their aversions to military interventions, France was realistic about its allies’ capabilities to conduct the necessary aerial operations. Few European countries have the ability to conduct policing in their own air spaces while also sustaining deployment abroad. Denmark, for instance, temporarily suspended involvement in Iraq in September, to perform maintenance on fighter jets and rest its pilots.

Perhaps in light of these facts, no member state has previously invoked the EU mutual defense clause. Though many European policymakers involved in its formation hoped it would be as robust a requirement for the EU as Article 5 of the NATO treaty, its theoretical ambition has until now remained untested and could possibly not live up to expectations in practice.

With this in mind, France likely, and somewhat paradoxically, invoked the clause to avoid putting its European partners in an uncomfortable situation. It did not expect other governments to actually employ “all means in their power,” only to display a sense of solidarity. In addition to those outlined above, all remaining EU member states will certainly look to provide some form of assistance, though it could be of an indirect nature. For example, Ireland—officially a neutral country—has indicated it may send troops to Mali or Lebanon, to allow French troops stationed there to be reassigned. Many other governments have yet to reveal what they will provide, and there may well be disappointments along the way.

European contributions in light of the Paris attacks form a patchwork rather than a true collaboration, and will likely continue to do so. This may be partly due to the nature of the mutual defense clause, which required France to conduct separate bilateral negotiations with its 27 EU partners, in place of likely even more difficult and ineffective communal talks. These would have once again shown the precarious solidarity among EU member states and the lack of robustness of its foreign and security policy. The French clearly had no time for lengthy debates in Brussels.

In the end, the offer of active support by several member states is likely to overshadow the absence of meaningful commitment from others. On balance, the picture will not be too disheartening for supporters of the EU model: its foreign and security policy apparatus will not come out damaged, but only because they have not been properly tested.

Vivien Pertusot is the Head of Brussels Office for the French Institute of International Relations.