In an example of growing high-level interest in the topic of disinformation, the Nobel Foundation along with the US National Academy of Sciences hosted a three-day summit on disinformation last May.

The 2023 United Nations climate change conference (COP28), which wrapped up in December, took place amid a swirl of false and misleading claims about the climate crisis. Much of this misinformation originated and spread online, fueled by far-right websites and left unchecked by social media platforms.[1] Some of it also came in the form of digital ads from fossil fuel companies. And at the conference itself, a record number of fossil fuel lobbyists were granted access, including more than 160 with a record of climate change denial.

This misinformation threatens to further slow the action urgently needed to address climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underscored the impact of climate misinformation in its 2022 assessment report. The report concluded with “high confidence” that “rhetoric and misinformation on climate change and the deliberate undermining of science have contributed to misperceptions of the scientific consensus, uncertainty, disregarded risk and urgency, and dissent.”

Yet while misinformation has been stymying climate action for decades, it has only gained high-level attention in the past couple of years. The IPCC’s 2022 report was its first to assess the impact of climate misinformation (and only in the section on North America), and it was only in 2022 that climate misinformation emerged as a clear priority at the highest levels of the United Nations (UN). This was reflected in a call for action against “rampant climate disinformation online” and the publication of a “roadmap to prevent net zero from being undermined by false claims, ambiguity and ‘greenwash.’” Climate misinformation was also a major focus of the secretary-general’s June 2023 policy brief on information integrity on digital platforms. Still, climate misinformation has never been on the agenda at COP or been mentioned in any of the COP outcomes, despite organized advocacy by climate activists.

By contrast, misinformation on other topics attracted high-level attention earlier. This is especially true for misinformation related to elections, which has often been the focus of policymakers, especially at the national level. It is also true for health-related misinformation. As outlined in a recent report I co-authored, following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, many of the national and international institutions leading the response to the pandemic quickly recognized that they also needed to respond to the related “infodemic.” This led to a flurry of initiatives to address misinformation about COVID-19, including from the World Health Organization (WHO).

Moreover, in contrast to COP, the infodemic has consistently been on the agenda of negotiations among WHO member states on an agreement to strengthen global pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response, which have been ongoing since 2022. While the final agreement is still taking shape, the most recent text, from October 2023, states that “the Parties shall strengthen science, public health and pandemic literacy in the population, as well as access to information on pandemics and their effects and drivers, and combat false, misleading, misinformation or disinformation.”

Considering that the climate crisis predated the COVID-19 pandemic, why has attention on climate misinformation lagged? And how can efforts to tackle climate misinformation learn from and build off of similar efforts in the field of health?

Why the Delay in Focusing on Climate Misinformation?

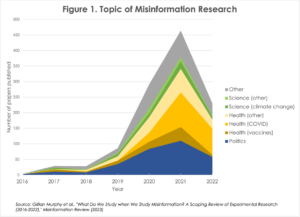

One of the main reasons for the lag in high-level multilateral attention to climate misinformation is that the issue of misinformation itself only fully entered the spotlight in 2016 following the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union and that year’s US presidential election. Over the next few years, the focus remained largely on political misinformation before rapidly shifting to COVID-19 in 2020. By 2022, 52% of all published papers on misinformation focused on COVID-19, while just 6% focused on climate change, according to a recent study (see Figure 1).  This difference in attention makes sense considering the pandemic was a sudden, fast-moving crisis, while the climate crisis is a longer-term, slower-moving catastrophe. Moreover, different crises tend to compete with each other for attention, as reflected in the 80% drop in online sharing of climate change content following the outbreak of COVID-19. As COVID-19 recedes from the public consciousness—even as the pandemic continues—while climate-related disasters escalate, this relative attention may shift.

This difference in attention makes sense considering the pandemic was a sudden, fast-moving crisis, while the climate crisis is a longer-term, slower-moving catastrophe. Moreover, different crises tend to compete with each other for attention, as reflected in the 80% drop in online sharing of climate change content following the outbreak of COVID-19. As COVID-19 recedes from the public consciousness—even as the pandemic continues—while climate-related disasters escalate, this relative attention may shift.

The relative recency of high-level attention on climate misinformation may explain its absence from the agenda at COP. Negotiators at COP are generally reluctant to discuss any issues not covered by the Paris Agreement, which does not mention misinformation—an unsurprising omission considering the agreement was adopted in 2015, before misinformation was a top concern for policymakers. By contrast, negotiations on the pandemic agreement are taking place following a major spike in attention on the issue.

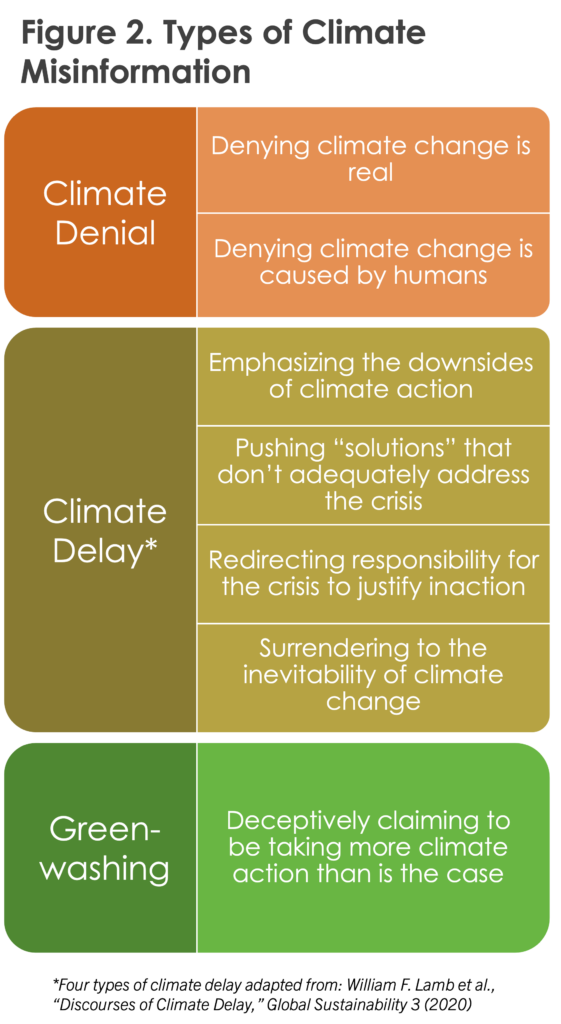

One reason climate misinformation may still not register as a top priority for climate action is that it has become harder to identify due to changes in the tactics of those spreading it (see Figure 2).  Increasingly, the goal of those spreading climate misinformation is not to deny that the earth is warming—which is growing more and more difficult to reconcile with reality—but to “discredit any proposal for mitigation, adaptation and transition.” One recent study found that the proportion of climate misinformation on YouTube that used such “discourses of climate delay” jumped from 30% to 65% between 2018 and 2023, while the proportion outright denying climate change dropped from 65% to 30%. Climate misinformation also increasingly takes the form of “greenwashing,” whereby companies or states mislead the public by claiming to be fighting climate change without meaningfully doing so. Other times, climate misinformation doesn’t have a discernible goal beyond getting more clicks or followers.

Increasingly, the goal of those spreading climate misinformation is not to deny that the earth is warming—which is growing more and more difficult to reconcile with reality—but to “discredit any proposal for mitigation, adaptation and transition.” One recent study found that the proportion of climate misinformation on YouTube that used such “discourses of climate delay” jumped from 30% to 65% between 2018 and 2023, while the proportion outright denying climate change dropped from 65% to 30%. Climate misinformation also increasingly takes the form of “greenwashing,” whereby companies or states mislead the public by claiming to be fighting climate change without meaningfully doing so. Other times, climate misinformation doesn’t have a discernible goal beyond getting more clicks or followers.

As climate misinformation has become more subtle, its impact may not always be obvious. Despite the efforts of fossil fuel lobbyists, survey after survey after survey demonstrates that public belief in climate change and support for climate action remain strong across the globe. Moreover, the public tends not to trust business leaders to tell the truth on climate change, while trust in scientists remains high, which could make the public resilient to climate misinformation. However, public support for climate action in general does not necessarily signify robust support for the transformative actions needed. For example, carbon pricing, which has been called the “last, best hope for averting climate disaster,” lacks majority support in many countries, as does regulations limiting emissions. This is why fossil fuel lobbyists now use misinformation less to deny climate change than to undermine support for specific policies. Looking below the top-line survey numbers reveals the potential effectiveness of these tactics.

The Link between Misinformation on Climate and Health

While it is encouraging that climate misinformation has begun getting some high-level attention, focusing on misinformation on this one topic in isolation may not be the most effective approach. Climate misinformation exists within a broader information ecosystem and needs to be understood in this context. It is particularly useful to look at the intersection between misinformation on climate and health.

One reason for this is that similar networks are spreading misinformation on climate and health. A recent network analysis of distrust on Facebook found “significant conversation overlap between COVID-19 and climate change, particularly in global communities.” This overlap may be increasing. A network analysis of Twitter/X found that the share of accounts spreading climate misinformation that were also spreading COVID-19 misinformation nearly doubled between 2021 and 2022, from 12% to 22%. This reflects a trend whereby COVID-19 denialists are shifting their focus to climate denial as public interest in COVID-19 decreases. There is also evidence of the reverse, as long-time climate denialists have started spreading misinformation about COVID-19.

One reason for this overlap is that health-related and climate change skepticism are both associated with similar worldviews. There are also important ideological differences between skeptics on these two issues, particularly between countries. But studies have found that belief in misinformation about both climate change and COVID-19 is associated with a lack of trust in science. This makes sense, given that both types of misinformation entail a rejection of scientific consensus (unlike misinformation on topics such as elections). This skepticism of science, in turn, has been found to be associated with conspiratorial thinking. One reason for this, according to psychologists who have studied this issue, may be that “conspiracy theories… tend to focus on the alleged wrongdoings of institutions, elites, and authorities, including… scientists.” Some conspiracy theories even link climate and COVID-19. For example, the “climate lockdown” theory held that “the COVID-19 pandemic was merely a precursor to future ‘green tyranny,’ and that both governments and global elites would curtail civil liberties under the pretext of climate change.”

It follows that similar strategies could be used to address misinformation on both climate and health. For example, both can be addressed through “prebunking,” or inoculating people against misinformation before they encounter it. This approach has been found to be effective in addressing misinformation on climate change as well as misinformation on vaccines in general and COVID-19 specifically. Moreover, logic-based (as opposed to fact-based) prebunking can address misinformation on multiple topics at once by building critical-thinking skills. Building these skills is also the most effective intervention against conspiratorial thinking, which is resistant to most other interventions.

Relatedly, some of the infrastructure developed to address health-related misinformation could also be used to address climate misinformation. This may not be possible for institutions like WHO whose mandates are issue-specific, but institutions with cross-cutting mandates could broaden their focus beyond specific types of misinformation. For example, the UN’s Verified initiative, which was launched in 2020 to address the COVID-19 infodemic, recently launched a partnership with TikTok to address climate misinformation (though this arguably could be seen as a form of greenwashing by TikTok considering the platform’s struggles to implement the ban on climate misinformation it announced in April 2023).

Looking beyond misinformation, strategic communication to build support for public health measures and climate action could benefit from shared messages and messengers. One study launched during COP28 presented evidence that informing the public about the “health relevance of climate change… holds significant promise for increasing public engagement with the issue and building support for climate change.” There is also evidence that health professionals could serve as trustworthy climate advocates.

However, any long-term solutions to misinformation, whether on climate change, COVID-19, or any other topic, will need to go beyond interventions like public education or prebunking that focus on individuals. There are still shortcomings in the evidence that such interventions are effective in the real world, in the long term, and across platforms and contexts (notably, most studies on misinformation have been conducted in the US). Moreover, researchers have tended to focus on how to address blatant falsehoods and conspiracy theories rather than the more subtle misinformation found in tactics like greenwashing. A long-term solution will require systemic interventions that transcend any individual issue, including stronger policies to limit the spread of misinformation on social media. The European Union took a step in the right direction in January by clamping down on greenwashing. Another positive step could be the UN’s forthcoming Code of Conduct for information integrity on digital platforms, which will set global standards for understanding and addressing all types of misinformation.

Ultimately, a disjointed approach to misinformation will be ineffective. As misinformation researcher Claire Wardle recently argued, “The field is siloed, organized by nation state or topic (elections, health, climate), whereas those who aim to pollute and influence our information landscapes… seek opportunities on any number of topics and are highly organized and networked.” What we need is a cross-cutting, systemic approach to information integrity, not a hodgepodge of initiatives to prebunk or debunk falsehoods on specific topics at the individual level.

Albert Trithart is Editor and Research Fellow at the International Peace Institute (IPI).

[1] This article uses the term “misinformation” for consistency, though much of what it discusses could be considered “disinformation.” The distinction is the intent: misinformation is false information spread without malicious intent, while disinformation is false information spread with malicious intent.