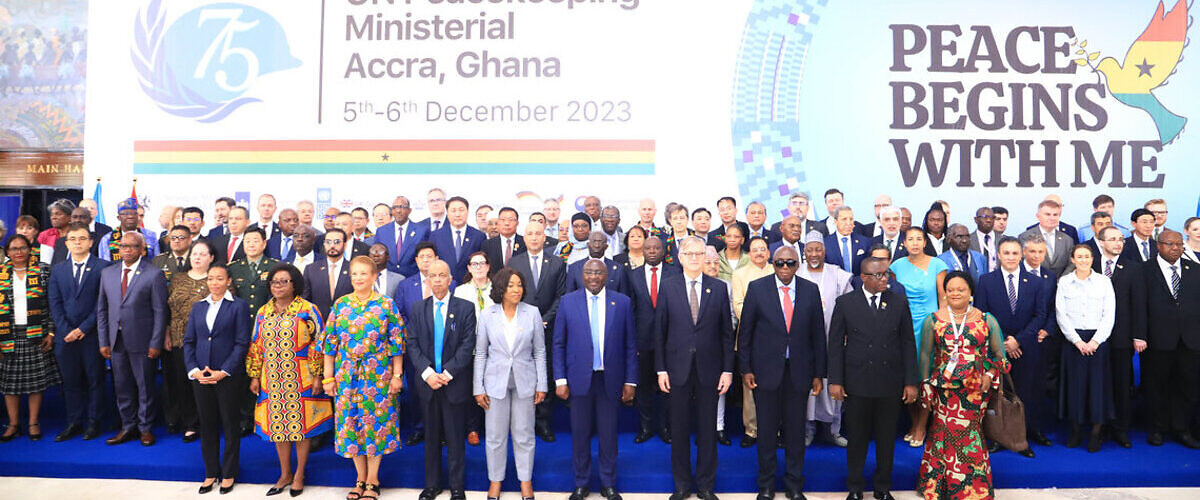

In December, United Nations (UN) member states gathered in Accra, Ghana for the 2023 UN Peacekeeping Ministerial—the seventh high-level peacekeeping conference to be held since 2014, and the first one on the African continent. The conference took place against the backdrop of significant shifts in the peacekeeping landscape, including the drawdown of two large UN missions and the growing role of regional and sub-regional organizations in peace operations settings.

Also taking place at this time were negotiations within the UN Security Council on financing for African Union (AU)-led peace support operations, with the Council passing a resolution shortly after the Ministerial’s conclusion. Thus, it was particularly significant that the Ministerial was hosted by an African member state that is also a major troop- and police-contributing country to UN peacekeeping operations.

While the past year has seen much discussion on the limitations of UN peacekeeping and the need to expand the tools available to address security crises, the conference in Accra illustrated strong member state support for the centrality of UN peacekeeping as a tool for collective security. Delegations from 91 member states attended to affirm their commitment to strengthening UN peacekeeping operations. A total of 57 member states announced new pledges to UN peacekeeping, including the provision of military and police personnel, training, equipment, and other capacities in line with the Action for Peacekeeping Plus (A4P+) priorities.

The priority themes identified for this year’s Ministerial reflect several long-standing areas of interest for the Secretariat and member states, including women peacekeepers, safety and security, mental health of uniformed peacekeepers, strategic communications, and the protection of civilians. In the lead-up to the Ministerial, preparatory conferences were held on each topic by member state co-chairs, with a virtual session on mental health convened by the Department of Operational Support (DOS).[1] The two-day Ministerial also featured two side events on women peacekeepers and environmental management, hosted by Sweden and the US respectively.

At first glance, the Ministerial was nothing out of the ordinary, with a broad cross-section of member states reiterating their support for UN peacekeeping and emphasizing the need to adequately train and equip peacekeepers to face the challenging security environments to which they are deployed. Yet, given policy discussions over the past year, this in itself is significant. Less than a year ago, many stakeholders were questioning whether we had reached the end of UN peacekeeping. At the very least, there was a prevalent sense that the UN would no longer deploy large multidimensional peacekeeping operations, which would be downsized in favor of lighter footprint political presences. However, if that sentiment remains, there was no trace of it at this year’s Peacekeeping Ministerial.

The following article draws out this and other key themes from this year’s Peacekeeping Ministerial and what they may mean for the future of peacekeeping.

Key Takeaways

While much of the UN Peacekeeping Ministerial functions as a pledging conference and can therefore be technical in nature, the statements made by more than 50 member states, regional organizations, and senior UN officials provided insight into stakeholders’ broader views on UN peacekeeping. First, A4P and A4P+ continue to serve as central frameworks for supporting effective UN peacekeeping. Since they were launched in 2018 and 2021 respectively, A4P—including the associated Declaration of Shared Commitments—and A4P+ have been the primary policy frameworks through which member states and the Secretariat channel support for UN peacekeeping. However, the initial phase of A4P+ concluded at the end of 2023 with no official announcement from the Department of Peace Operations (DPO) whether or how it would be taken forward. This, coupled with the release of the New Agenda for Peace, has left some wondering what the future would be for A4P+, including whether its priorities remain fit for purpose given significant changes to the peacekeeping landscape.

While DPO has still not made a formal announcement on its vision for the next phase of A4P+, the Under-Secretary-General for Peace Operations, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, did note during the Ministerial that that the UN would continue its efforts to strengthen peacekeeping through A4P and A4P+ for “the foreseeable future.” Multiple member states also reaffirmed their support to the policy frameworks in their statements, and the priorities of A4P+ guided the requests of DPO in its pledging guide and many of the commitments made by member states. Thus, while DPO would do well to further unpack how it envisions taking these frameworks forward in the context of the New Agenda for Peace and a changing peace and security landscape, it seems likely that they will continue— at least for the time being—as central pillars for support to UN peacekeeping.

Second, peacekeeping is understood by member states and UN officials to be under tremendous strain right now, given the difficult security environments missions are deployed to, high levels of risk to peacekeeper safety and security, mis- and dis-information, advances in technology, resource constraints, and divisions within the Council. All of these factors make it more difficult for peacekeepers to implement their mandates, which can undermine trust with local communities. Thus, stakeholder statements regularly emphasized the need to improve the resources, equipment, and training provided to peacekeepers. This includes, for example, support to the effective use of technology – in line with the Strategy for the Digital Transformation of Peacekeeping, training on C-IED, deploying specialized personnel to address issues like peacekeeping-intelligence and mis- and dis-information, and providing equipment that is properly fitted for women peacekeepers. These efforts are also in line with the A4P and A4P+ commitments to improving peacekeeper safety and security and accountability to peacekeepers.

Third—and as noted above—the Ministerial illustrated strong commitment from a broad cross-section of member states to the future of UN peacekeeping. While UN peacekeeping has been a central tool in collective security for the past 75 years, events of the past year placed its future in question. Not only have multiple missions faced significant crises, but current policy frameworks—including the New Agenda for Peace and efforts to finance AU-led operations—suggest that robust measures may be left to other actors, with the UN focusing on political presences and logistics support. To be clear, there is a strong sense that UN peacekeeping needs to continue to adapt, or it risks becoming irrelevant to today’s political and security landscapes. However, representatives from nearly every region of the world reiterated their commitment to supporting UN peacekeeping as a central institution that should be further strengthened, even as it adapts to current demands.

Among the member states that provided such statements were African member states, who were unsurprisingly well-represented given the location of the Ministerial. Yet, continued support for UN peacekeeping by African member states has not been a given. While some member states did reference the need for the UN to seek sustainable and predictable financing for AU-led peace support operations, this issue was presented primarily as a complement to, rather than supplement for, UN peacekeeping.

Conclusion

The last 18 months have presented numerous challenges for UN peacekeeping, including deadly riots against the UN mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the sudden closure of the UN mission in Mali, an increasingly fractured UN Security Council, and protracted crises across multiple regions of the world. Yet, far from crumbling under the weight of these challenges, UN peacekeeping has shown itself adaptable—a trait that it has embodied throughout its history. The Secretary-General’s recommendation in the New Agenda for Peace that member states evaluate the opportunities and limitations inherent to UN peacekeeping operations could be useful to support further adaptation.

Yet, it’s also worth emphasizing that UN peacekeeping is not the singular answer to international peace and security crises, and force-fitting it into contexts that are not appropriate for peacekeeping can come with severe consequences, as seen in Mali. Thus, support to strengthen UN peacekeeping should come alongside efforts to strengthen other tools and the work of other actors.

Nevertheless, the strong showing from member states at this year’s peacekeeping ministerial should quiet further claims that UN peacekeeping has met its end. At least for now, UN peacekeeping is the best tool member states have to support collective security. Preparations are already underway for the next UN Peacekeeping Ministerial, which will be held in Berlin in 2025.

———————————

[1] The preparatory conference on Women in Peacekeeping was held in Dhaka from 25-26 June 2023 and was co-hosted by Bangladesh, Canada, and Uruguay. The preparatory conference on Mental Health Support for Uniformed Peacekeeping Personnel was convened online on 18 July 2023 and was co-hosted by Ghana, the Republic of Korea, and the UN. The preparatory conference on Safety and Security of Peacekeepers was co-hosted by Pakistan and Japan and was held in Islamabad from 30-31 August 2023. The preparatory conference on the Protection of Civilians and Strategic Communications was co-hosted by Indonesia, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Rwanda, and was held in Kigali from 23-24 October 2024. Summaries of the preparatory conferences can be found here.