A flag raising ceremony for nine new members of the United Nations in 1992. (UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe)

The “crisis of multilateralism” has become a common refrain among commentators, especially since 2016 when the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union and Donald Trump won the United States (US) presidential election. More recently, the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have exacerbated fears that the multilateral system is broken. In his 2022 address to the UN General Assembly, Secretary-General António Guterres cited the “geopolitical tensions and lack of trust that poison every area of international cooperation.”

Underpinning many of these concerns is a fear that the United Nations (UN) is losing legitimacy, which could undermine its relevance as a forum for international cooperation and norm-making. But it is hard to assess whether the UN is indeed losing legitimacy. For one, the UN means different things to different people—while to some it may evoke the Security Council or General Assembly chambers in New York or the image of the secretary-general, others may think of the work of a specific UN agency or of UN peacekeepers; others still may think of an abstract global government that has little relation to the UN as it actually operates. Moreover, legitimacy is a difficult concept to assess and requires turning to rough proxies like trust or confidence.

Data on Public Confidence in the UN

What, then, does existing data show us about the public’s trust or confidence in the UN? One consistent finding across surveys is that trust and confidence in the UN are generally higher than for other multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and International Criminal Court and for regional organizations like the European Union (EU) and African Union. But beyond this, making generalizations is difficult, partly because the answer can vary from survey to survey.

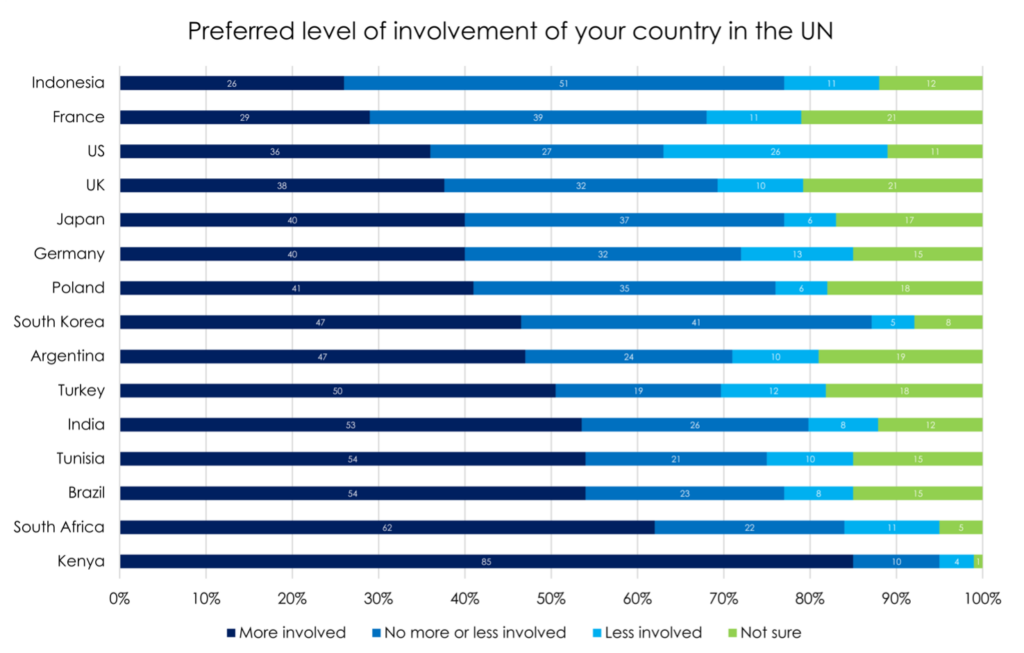

In some surveys, public support for the UN appears robust. A global-level 2020 survey by the consulting firm Glocalities found that 47 percent of the world’s population trusts the UN, compared to 27 percent that does not. Similarly, in both a 15-country 2022 survey by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) and YouGov and a 19-country 2022 survey by Pew, the UN’s net favorability was positive in nearly every country surveyed and at least +20 in a sizable majority. Moreover, in every country surveyed by FES/YouGov (except the US), well over twice as many people wanted their country to be more involved with the UN rather than less (and even in the US, the plurality favored greater involvement). A 36-country 2020 survey conducted for the UN by the communications firm Edelman also found that 62 percent of those surveyed who were aware of the UN agreed that it has made the world a better place, while 50 percent agreed that the UN has improved the lives of people in their country.

Source: European Values Study and World Values Survey, “Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2022 Dataset,” December 2022: R. Inglehart et al., eds., “World Values Survey: Wave 5 (2005-2009),” 2018.

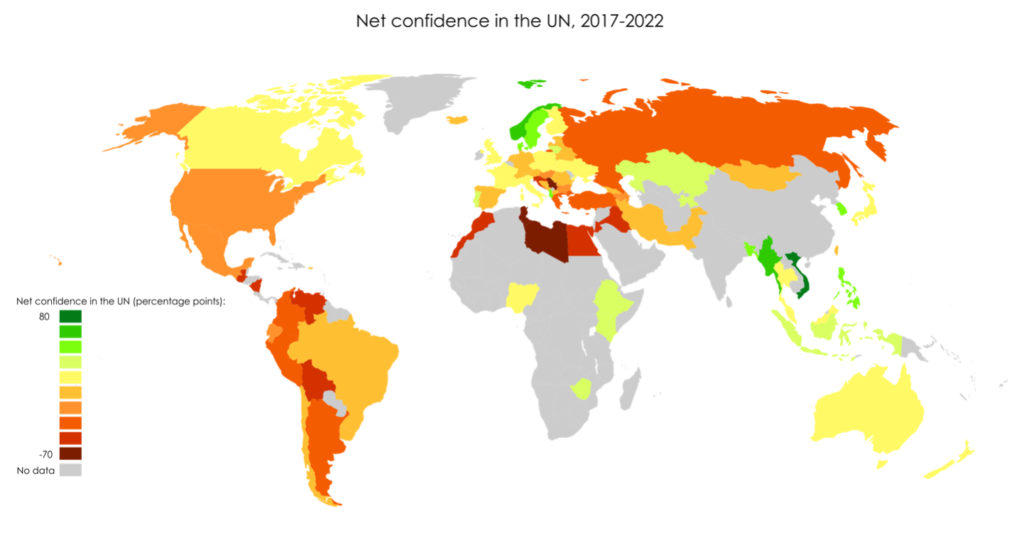

But a more pessimistic picture emerges from the 2017–2022 World Value Survey and European Value Survey (WVS/EVS), which cover around 90 countries and territories from every geographic region. Here, net confidence [1] in the UN was positive in only around half of the countries and territories surveyed, with many displaying remarkably low levels of confidence. (It bears mentioning that, apart from differing geographic samples, these surveys vary in whether they ask about trust, confidence, or favorability, which could play some role in explaining differences in results.)

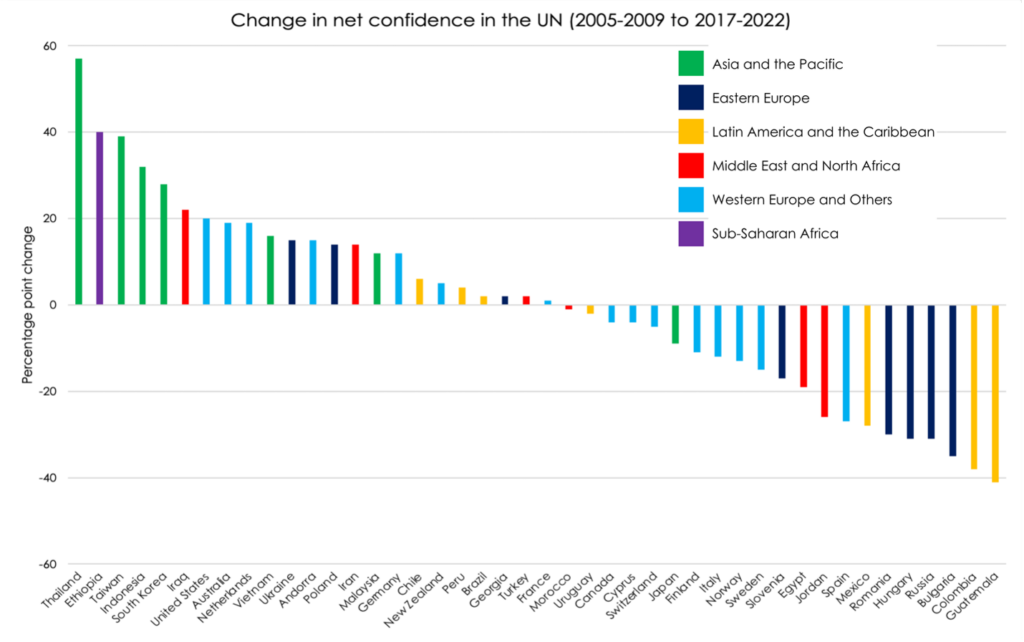

How have these perceptions of the UN shifted over time? Data from the WVS/EVS, which covers a longer time frame and more countries than other multi-country surveys, shows a slight overall decline in confidence in the UN since the mid-1990s. This decline in support for the UN parallels a broader decline in support for international organizations more generally. Beyond these longer-term trends, however, confidence in the UN seems to have remained fairly steady over the past decade, and it is difficult to make confident claims about the impact of recent global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the evidence is mixed. An Italian survey conducted at the outset of the pandemic in April 2020 found an increase in trust in national institutions but a decrease in trust in the UN. Similarly, a recent analysis of WVS data from 40 countries found that the pandemic decreased confidence in the World Health Organization (WHO) by half (though WHO, which is part of the UN system, started off with a higher level of confidence than the UN as a whole). By contrast, the Edelman Trust Barometer also found a slight year-on-year increase in trust in WHO in both 2021 and 2022. And in a 14-country Pew survey in summer 2020 and a 19-country FES/YouGov survey in 2021, a majority of respondents in most countries agreed that the UN “promotes action on infectious diseases, like coronavirus.” One major exception across all these surveys is Japan, where the UN and WHO’s favorability and trustworthiness have declined dramatically since 2020, which could reflect widespread perceptions at the outset of the pandemic that WHO was significantly influenced by China.

Source: Open Society Foundations, “Fault Lines: Global Perspectives on a World in Crisis,” September 2022.

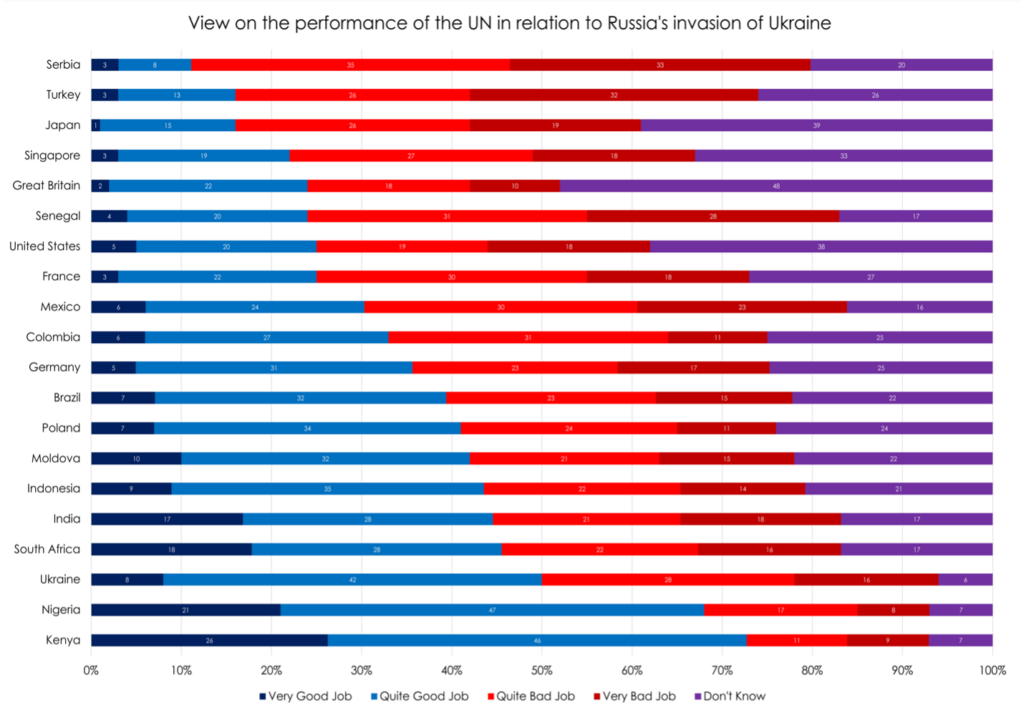

Compared to the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems more likely to have had a negative impact on perceptions of the UN. A survey of 22 countries conducted by the Open Society Foundations in summer 2022 found a mixed assessment of the UN’s response to the invasion. Negative views outweighed positive ones in most countries, including in all five of the G7 countries surveyed, and the UN’s response was generally viewed more negatively than that of the EU or NATO. However, there were some major exceptions: for example, assessment of the UN response was very positive in Kenya and Nigeria and relatively positive in Ukraine itself (though more than two in five Ukrainians saw the UN as doing a bad job). Similarly, in many of the countries surveyed by Pew, FES/YouGov, and the Edelman Trust Barometer in both 2021 and after the invasion in 2022, the UN’s favorability declined slightly, but again with many exceptions.

Source: European Values Survey and World Values Survey,” Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2022 Dataset,” December 2022.

One reason it’s difficult to identify concrete trends is the wide variation among countries and regions. According to WVS/EVS data, confidence in the UN has consistently been low across the Middle East and North Africa since at least the mid-1990s. Confidence also appears relatively low across Latin America and Eastern Europe, with a general decline over the past decade. Confidence appears especially low in several countries where the UN has deployed peace operations to address long-standing conflicts, including in the former Yugoslavia, Cyprus, Israel, Lebanon, Morocco, Iraq, Libya, Guatemala, and Colombia (countries with larger peacekeeping operations were not included in the survey). Meanwhile, people in several countries in Scandinavia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa have relatively high levels of confidence (while the WVS lacks data for China and India, other surveys have found that trust in the UN is also high in those countries).

There are also some notable differences among demographic groups within countries. In many countries, especially Western countries with strong right-wing nationalist movements, confidence in the UN is higher on the political left (the US is by far the most extreme example of this political divide, but it also shows up in countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, and Poland). But in other countries, especially countries with strong traditions of left-wing populism, it is people on the right who have more confidence in the UN (e.g., Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Spain, and Greece). This likely points to a political divide rooted more in populism and nationalism than in the left-right political spectrum.

When it comes to age, young adults are more favorable to and more trusting of the UN across most countries. But the WVS/EVS reveals some geographical variation. In 70 percent of the countries and territories surveyed, those aged 18–29 are significantly more confident in the UN than older generations (especially in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Western Europe). But in some countries, the trend is reversed, notably in Africa, where net confidence is highest among people aged 50 or over in five of the eight countries surveyed (Egypt, Tunisia, Nigeria, Kenya, and Zimbabwe), as well as in the Maldives (the only small island developing state surveyed).

Another relevant demographic variable may be minority status: one recent study based on data from the WVS found that ethnic minorities are more likely than ethnic majorities to have a high degree of confidence in the UN in countries experiencing ethnic conflict. The author theorizes that this is because ethnic minorities are likely to experience social, economic, and political discrimination from domestic institutions and are thus more likely to seek remedies from non-domestic institutions such as the UN.

This survey data requires a caveat, however. While the WVS and many of the other surveys cited here include data from multiple geographic regions, they are not representative of the global population. Most notably, Pew only surveys “advanced economies,” while the 46 least developed countries are dramatically underrepresented across all surveys: of the 90 countries and territories surveyed in the most recent round of the WVS/EVS, for example, only 3 fall into this category (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Myanmar). Moreover, none of these cross-country surveys cover the countries hosting multidimensional UN peacekeeping operations.

This gap could present a warped picture of the UN’s legitimacy, in part because people in developed countries, who are overrepresented in existing survey data, are far less likely to interact with the UN directly. Meanwhile, the people most likely to interact directly with the UN—for example, people receiving humanitarian assistance or protection—are mostly left out of the data. This gap is especially problematic because the UN will be less effective at delivering on its mandate if it lacks legitimacy among those it is most directly meant to serve and protect.

Accounting for Public Confidence in the UN and Understanding How to Increase It

These findings leave a lingering question: What accounts for people’s confidence in the UN or lack thereof? Researchers have identified at least four factors. One of the most important factors seems to be people’s confidence in domestic political institutions. Because most people are not very familiar with the UN and what it does, they may be more likely to base their opinion of the UN on their opinion of more familiar domestic institutions. Indeed, several studies have found that people who trust their domestic political institutions are also more likely to trust the UN.

One implication of this is that the UN may have limited control over what people think of it. The UN itself cited this limitation in a 2019 evaluation of the Department of Public Information (since renamed the Department of Global Communications), noting the “low attribution levels of public opinion about the United Nations to the Department’s work” due to the strong influence of “external factors, such as national-level political trends.” This could limit the impact of UN public information or strategic communications efforts to bolster support for the organization.

By comparison, domestic elites may have more influence over public perceptions of the UN. One study based on a 2015 survey in Germany, the UK, and the US found that communication from domestic elites is more effective at swaying public support for the UN than communication from the UN itself. This finding may sound concerning, considering the hostile rhetoric some prominent elites have directed at the UN and other multilateral institutions. However, there is little evidence that elites have broadly turned against the UN. Based on a six-country survey of elites (including political and bureaucratic elites) conducted from 2017 to 2019, one recent study found that “the evidence does not show a ‘crisis’ of elite confidence in global governance.” The authors instead found a moderate level of confidence in the UN, suggesting “a future of muddling through on global governance.” Another study based on the same survey found that elites tend to have higher confidence in the UN than the general public.

However, other factors that have been found to account for people’s confidence in the UN are more within the UN’s control. A second factor is institutional performance. For example, one study using WVS/EVS data found that the legitimacy of the UN may be mainly attributable to its “capacity to solve societal problems and generate benefits.” In this regard, there may be differences in what types of societal problems people have confidence that the UN can solve. In a 2020 Pew survey of 14 developed countries, respondents were most likely to credit the UN with promoting human rights and peace; they were much less likely to believe that it “deals effectively with international problems” or “cares about the needs of ordinary people.” By contrast, in a 2020 Edelman survey, respondents in developing countries who were aware of the UN had a broadly positive assessment of its role in addressing global problems. Overall, the importance of institutional performance means that the UN should be able to bolster its legitimacy by effectively addressing the issues that matter most to people, including protecting the environment, improving access to education and healthcare, ensuring respect for human rights, and preventing and resolving conflict.

A third factor is institutional procedures. For example, one four-country 2016 survey found that people see the UN as more legitimate when they believe that it operates democratically, fairly, and efficiently. The importance of institutional procedures suggests that the UN could bolster its legitimacy by taking on board some of the proposals that emerged from the hundreds of dialogues organized worldwide by the UN on its 75th anniversary in 2020. Above all, these included involving more women, youth, local authorities, and civil society organizations in decision-making; increasing accountability and transparency; and upgrading the organization, including by reforming the Security Council and bolstering peacekeeping.

A final factor to consider in accounting for public confidence in the UN is that many people are not aware of the UN or have limited knowledge of it. A 36-country 2020 survey found that around 40 percent of respondents said they “know little or nothing about the UN.” This could partly be explained by the fact that, according to a 70-country analysis in 2020, the UN receives limited media coverage; for example, just 3 percent of 87 million media mentions of conflict referenced the UN. Needless to say, the UN cannot be seen as legitimate (or illegitimate) by people who don’t know what it is.

Overall, survey data does not reveal a major, widespread drop in the UN’s legitimacy over the past few years. But at the same time, confidence in the UN is fairly tepid overall and quite low in some parts of the world. Any efforts to bolster the UN’s legitimacy should account for this geographic variation, as well as variation in confidence among different groups of people within countries. Truly understanding the UN’s legitimacy also requires more data on the perceptions of those who are most directly impacted by the UN’s work, including people in countries where UN peacekeepers are deployed. Ultimately, the UN is an organization of “we the peoples,” and for it to remain that way, it needs the people’s support.

[1] Net confidence is the difference between the percentage of respondents who have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence and those who have “not very much” confidence or “none at all.”

Albert Trithart is Editor and Research Fellow at the International Peace Institute (IPI). Olivia Case is Editorial Intern at IPI.