Shoppers and vendors at Bandim Market, Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, May, 2012. On July 10, 2013, a senior UN official said that planned November elections can't be seen as free and fair unless progress is made on investigations of recent high-profile political killings. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, File)

In June 2022, the United Nations (UN) Peacebuilding fund (PBF)’s top donors will discuss strategies for better supporting peacebuilding processes. Following a high-level meeting on peacebuilding financing in April 2022, the gathering will be an opportunity to support countries adversely affected by limited funding, including the so-called “aid orphans.” Guinea-Bissau is one of the most tragic examples, and it illustrates how sparse peacebuilding financing makes them particularly vulnerable.

The history of Guinea-Bissau is characterized by poor governance, corruption, weak rule of law, and unconstitutional governmental transitions, among other issues. There have been at least four coups (in 1980, 2003, 2010, and 2012), a violent war in 1998 and 1999, and the murder of President Nino Vieira in 2009. Only one president has succeeded in completing his term since the country gained independence in 1973, José Mario Vaz, in 2020.

The frequent instability in the country remains a crucial concern for the country’s peacebuilding process. Uncertainty around elections was showcased by another parliament dissolution in May 2022. At the local level, increasing tension around the land, sectoral strikes, a rise in hate speech and polarization of political discourse—often with a religious undertone—threaten the country’s stability.

The constant instability of the Bissau-Guinean political environment has led to a fractured and contested environment for peacebuilding planning. The government and the international community developed various policy frameworks to create an environment conducive to developing and implementing peace processes. However, implementation for many of these priorities remains contested, unresolved, and in demand in the country, including security sector reform; justice sector reform; economy and infrastructure; social issues; public administration reform, elections, and institution building.

The number of policies and programs, often overlapping, creates a major challenge for peacebuilding planning and implementation in Guinea-Bissau. The majority of the peacebuilding interventions in the country have focused on democratic governance—particularly political dialogue and national reconciliation—and security sector reform. However, due to political challenges, many peacebuilding initiatives have been disrupted. For instance, in the wake of the 2012 coup, many donors withdrew financial assistance, resuming the work a few years later.

The lack of continuity in peacebuilding interventions is exemplified by the recent changes in national planning processes. The 2016 national plan, Terra Ranka, was the roadmap for implementing governmental and national peacebuilding responses. But since the new government came into place in 2020, the plan was replaced by a new governmental vision, Hora Tchiga, with a developmental orientation. There is a visible political “fatigue” toward peacebuilding discourse within many governmental circles and a stronger inclination to instead discuss development.

Despite the instability it faces, Guinea-Bissau—alongside countries like Madagascar, Chad, or the Central African Republic—has long been overlooked by donors. There is an urgent need to re-orientate the international community toward supporting and financing conflict prevention and early action. Donor fatigue, further compounded by the withdrawal of the UN integrated peacebuilding mission in 2020 (UNIOGBIS), has left the country in a precarious state.

In recent years, international support has been organized mainly by the so-called “Guinea-Bissau P5,” led by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Other members of the P5 are the African Union (AU), the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), the European Union (EU) and the UN. Despite the role of the P5, international financing for peacebuilding remains provided mainly by the UN Country Team (agencies, funds, and programs) and a limited number of donors, like the EU and Japan.

The difference in styles between these prominent donors is clear. The UN, particularly through the PBF, is generally perceived as having “substantive flexibility” but rigidity in funding eligibility. The EU often provides larger funding amounts but is bureaucratically restrictive and with many transactional costs concerning managing the projects. Japan, a relative newcomer as a donor, pursues a unique approach in the country, in line with its roles in other countries. It does not work directly with governments or civil society organizations, implementing it through a UN Development Programme (UNDP) partnership.

The case of the UN PBF is elucidating. The PBF is meant to be a catalyst for change, providing short to medium-term funding for peacebuilding initiatives. It has the mandate to catalyze and assist activities that help prevent conflicts and sustain peace. In most PBF-recipient countries, the fund is seen as minor compared to other donors. In Guinea-Bissau, however, PBF allocations could easily match those of other more significant donors and are, in fact, one of the country’s top funders of peacebuilding initiatives.

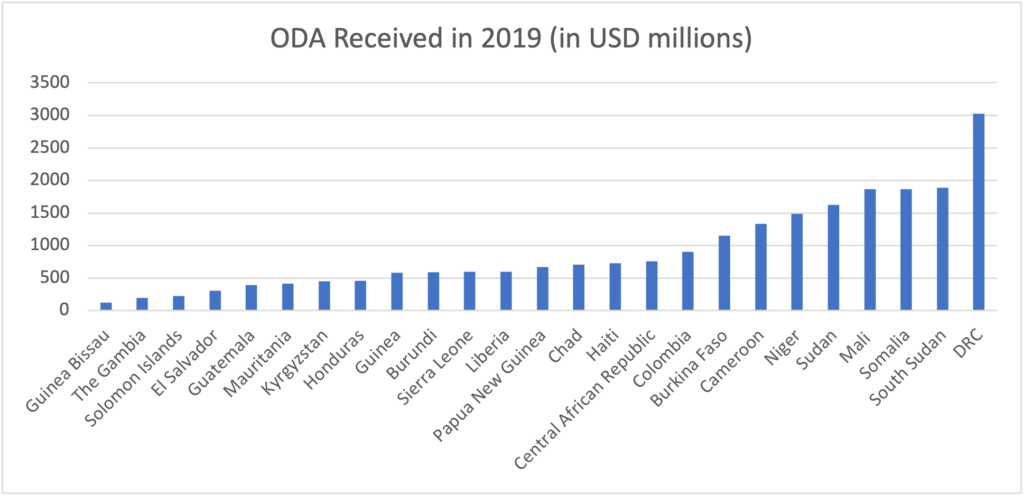

Of the 25 countries eligible for the PBF resources, Guinea-Bissau receives the least official development assistance (ODA), USD 120 million, as of 2019. UN PBF contributions—in the range of $12 million in 2022—are approximately 10 percent of the development assistance funding Guinea-Bissau gets every year, compared to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or Somalia, where PBF funding corresponds to only about 1 percent of the total ODA received.

Credit: Collected by the author from Aid at a glance charts

Much can be done to ensure a better landscape for supporting peacebuilding in Guinea-Bissau.

First, recent interviews in Guinea-Bissau by this author show that few national beneficiaries feel fully included in the design of peacebuilding processes. The financing of peacebuilding projects should be done more broadly to ensure that priorities are not only “accepted” by internal actors. Instead, external actors should pursue a more substantial buy-in and sense of national ownership in ensuring that different peacebuilding players effectively internalize peacebuilding priorities.

Despite developing joint strategies with the international community, government actors engaged in peacebuilding initiatives also lack the resources to conduct them. The government rationale for partnering with external actors is often described through the lens of limited funding or resources to engage in priority areas and limited ownership of financing priorities.

National actors are often included in later parts of defining peacebuilding initiatives, making their capacity to influence the definition of priorities and strategies of action limited. Capacity building processes should include national actors when possible, identifying opportunities to put them in the driving seat.

Second, civil society organizations have played a critical role in advancing the peacebuilding agenda in Guinea-Bissau despite many challenges. The weakening of institutions, and lack of access to services, have created a space where there is limited trust in the state or expectation of its intervention. While civil society groups have essential human resources, they are frequently faced with a lack of institutional support, including funding. Bringing a more comprehensive range of players to negotiating spaces may be one of the main ways to ensure funding priorities reach where they are most needed.

Third, peacebuilding is increasingly seen as a holistic approach. The Sustainable Development Goals, particularly goal 16, which states that peace and development complement one another, made this understanding clear. Yet, conceptual integration has not translated into integrated and complementary financing and programming of peacebuilding activities on the ground in Guinea-Bissau. There is much that international actors need to do to ensure that responses have clear intentionality to improve the peacebuilding landscape.

Though many projects have sought stronger participation of women and youth in decision-making processes, particularly the gender and youth promotion initiative (GYPI), funded by the PBF, which aims at increasing the focus of groups that are marginalized in society. The participation of women in political processes has been the focus of several organizations in through awareness raising, capacity building and advocacy. Hundreds of women leaders, for instance, have been trained in creating spaces for dialogue, ensuring that their voices are strengthened in the capital and in the country’s eight regions. Such projects are increasing the visibility of the women in political processes, including through their role at national level institutions and mediation activities.

Fourth, it is vital to strengthen the UN’s capacity to support an effective and inclusive peacebuilding process. Since the departure of UNIOGBIS, while some agencies were able to maintain a strong presence in the country, many struggled. Since 2021, many agencies were limited in their capacity to finance critical peacebuilding initiatives. Due to lack of funding, many agencies closed their doors in the country or moved the responsibility to other offices in the region. Limited funding meant that the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC) now mostly runs its activities from its office in Cape Verde, and agencies like UN Women ceased their presence in the country entirely.

The recently appointed UN Resident Coordinator will be vital to providing a clear direction by all agencies on their goals and how they should collectively implement their peacebuilding functions. His role is essential to ensure a coherent peacebuilding approach to the different UN agencies on the ground.

Fifth, while peacebuilding needs financial resources, it also requires political support, which is critical for the sustainability of any peacebuilding process. There is a need for better coordination among all stakeholders and partners involved in peacebuilding efforts in Guinea-Bissau. In particular, the government, international partners, and civil society actors working in peacebuilding can benefit from better coordination by establishing a common platform for exchanging information and coordinating activities.

The EU and the UN are already the most prominent peacebuilding donors in Guinea-Bissau. They should bring in other international donors, such as Portugal or Brazil, who can play a more significant role in supporting the peacebuilding process in Guinea-Bissau. Brazil, for instance, as the chair of the Peacebuilding Commission country configuration for Guinea-Bissau, could be far more active in playing a constructive role in supporting and financing peacebuilding in the country. Countries must be ready to invest substantial resources in the critical areas mentioned and increase their engagement with all stakeholders involved. The re-established UN PBF national steering committee can become a more critical tool and expand to include a broader range of partners.

Guinea-Bissau should avoid the pitfall of failing to address the structural nature of the problem by generating quick fixes that do not deliver long-term development outcomes. In considering how best to support the government of Guinea-Bissau in these areas, international partners will need to be aware of the challenges in financing peacebuilding initiatives. It is also essential to be conscious of its existing social and political tensions. To avoid providing resources that may fuel further disputes, it is necessary to engage with various stakeholders and civil society groups to identify priorities and the types of assistance required.

Peacebuilding is a long-term process, and thus it needs to be supported by the necessary resources and actors. The lack of funding for peacebuilding initiatives in Guinea-Bissau is a crucial issue that needs attention in order, ideally, to drive a more inclusive process of resource allocation. But there is much more to be done. With the end of UNIOGBIS, the future of how peacebuilding actors will operate remains uncertain. Bissau-Guineans must be empowered to ensure that the funds make a long-term impact on the communities in the country.

Gustavo de Carvalho is an independent public policy analyst and consultant based in Pretoria, South Africa. He previously worked as a consultant for the UN PBF Secretariat in Guinea-Bissau. The views of this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not reflect any official positions of the UN.