A view of fish vendors in a wholesale market in Dhaka, Bangladesh in August 2020. (Mehedi Hasan/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Attention to women’s economic empowerment and disempowerment has helped economies recover and grow in the past, and is an essential component of the global recovery from the coronavirus pandemic moving forward. COVID-19 has put all progress towards women’s empowerment made so far at risk, and experience from previous epidemics suggests that it will continue to impact groups who are most vulnerable and continue to amplify any existing inequalities. The results of a recent Future of Business (FoB) survey reinforce this insight, shedding light on some of the gender disparities in the economic impact of COVID-19.

The survey results demonstrate that women’s economic activities are found to be more unstable than men’s, and women are more likely to shoulder additional care work that has accompanied containment policies. Safeguarding women’s economic empowerment is critical to ensuring women are adequately protected from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, so that past gains made toward gender equity are not lost and progress can continue.

More Female Businesses are Closed than Male Businesses

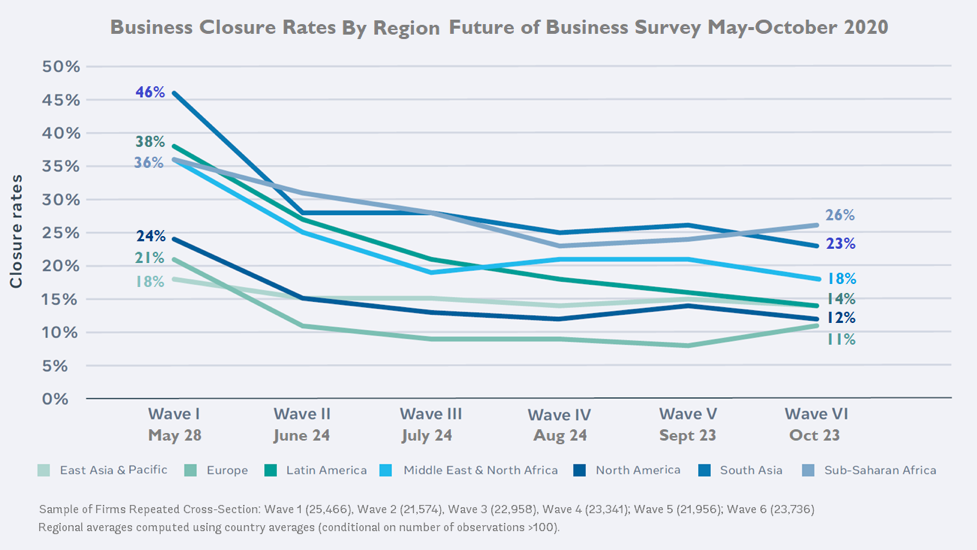

Survey results show a disparity between the number of female-led businesses and male-led businesses that were forced to close temporarily during the pandemic. The graph below shows the trend in the total percentage of businesses sampled that were temporarily closed within each region across the six waves of the FoB survey. Globally, 15 percent of businesses were non-operational during the wave VI (October) survey, the same as in the previous August and September waves, and lower than 16 percent in July, 18 percent in June, and 26 percent in May.

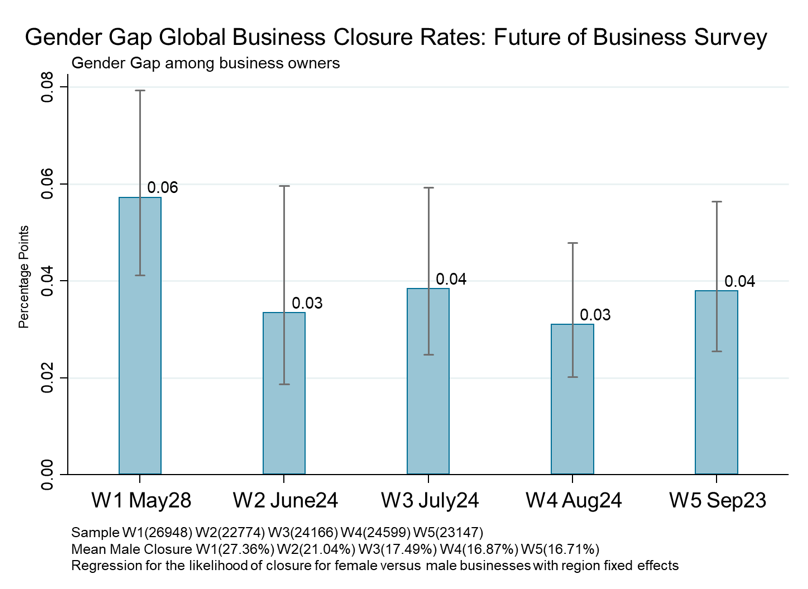

When these numbers are disaggregated by gender, we find female-led businesses were 5.9 percentage points (pp) more likely to have closed than those owned my males during wave I (May), taking into account regional attributes. Wave I can be considered the peak of the lockdown in many countries when closure rates and the gap was highest. However, a gender gap in business closures continues to persist even as closure rates improve (the graph below shows female-led businesses are 3-4 percentage points more likely to close their business than male-led businesses in the subsequent survey waves).

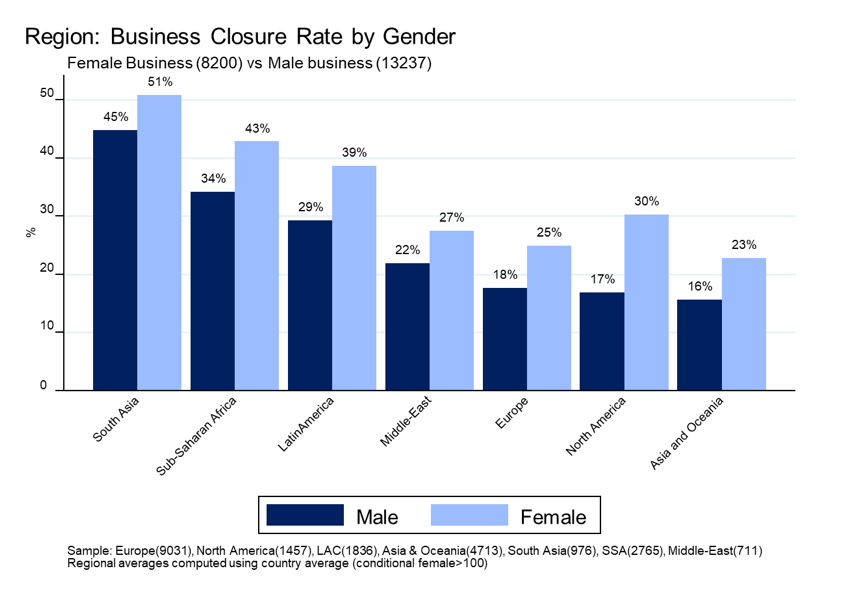

The gender disaggregated business closure rates by region at the time of the wave I survey is presented in the graph below. In all regions, among the countries sampled, a gender gap was found in business closure rates. In the sub-Saharan African countries sampled, for example, 34 percent of male-led businesses were temporarily closed at the time of the survey compared to 43 percent of female-led businesses.

The data suggests women entrepreneurs are being disproportionately affected by the contraction in economic activities as a result of COVID-19 for a number of reasons. First, women are more likely to close their business than men in countries with the strictest lockdown policies and they potentially are having to shoulder the extra care responsibilities that are required during a school closure or stay-at-home policy. Second, women are more likely to be concentrated in consumer-facing sectors (services, hospitality, retail trade) where the demand shock is hitting hardest. Third, in the regions where financial assistance in response to COVID-19 is limited, we find greater persistence in the gender gap in closures. A more detailed examination of the data on gender differentials in time spent on domestic responsibilities and sectors of operation and financing in response to COVID-19 can assist in developing policy responses.

More Impact in Sectors Where Women Operate

Globally, the sectors with the most business closures were: travel or tourism agencies (54 percent closed during late May 2020), hospitality and event services (47 percent), education and child care services (45 percent), performing arts and entertainment (36 percent), and hotels, cafes, and restaurants (32 percent). The biggest gender differences were in the type of services that men and women operate. For example, men are more likely to operate in the “professional services” sector, which faced relatively lower business closures than “education and childcare services” and “wellness, personal grooming, sports, and fitness services,” where women business owners are more likely to be concentrated.

The consumer facing sectors where women are concentrated are potentially more exposed to an economic recession and present less opportunity to switch to home-based work activities. While accounting for sectoral differences narrows some of the gender gap in business closures it does not fully explain the difference.

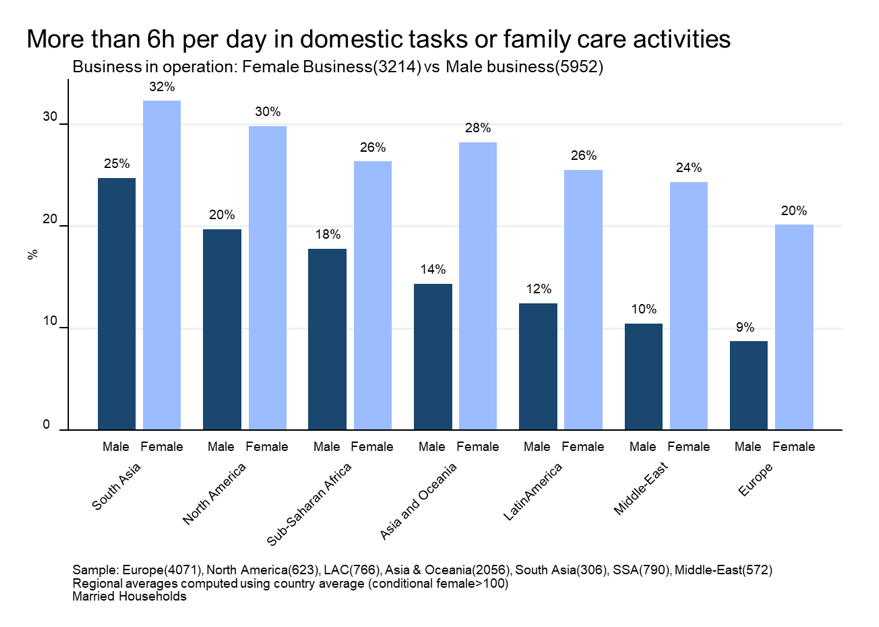

This pattern in closures could also be the result of the extra burden that may come from staying home during a quarantine or caring for children out of school or family members who have fallen ill or who no longer have access to non-family caregiving. Even among businesses that have remained operational, a large proportion of business owners/managers are having to manage domestic and care responsibilities, with women still doing the bulk of this work. The figure below based on wave 1 data shows that in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, 18 percent of married male business owners report they spend more than six hours per day on domestic and care activities while still operating their business. This compares to 26 percent of married female business owners.

This extra domestic burden is evident when respondents are asked what policies are most needed at this time. Female business owners who are married with young children report that their number one priority is support for taking care of household members, whereas for male business owners married with young children this ranks sixth in their list of policy needs. Limited Financial Assistance Means More Persistent Gender Gap

Limited Financial Assistance Means More Persistent Gender Gap

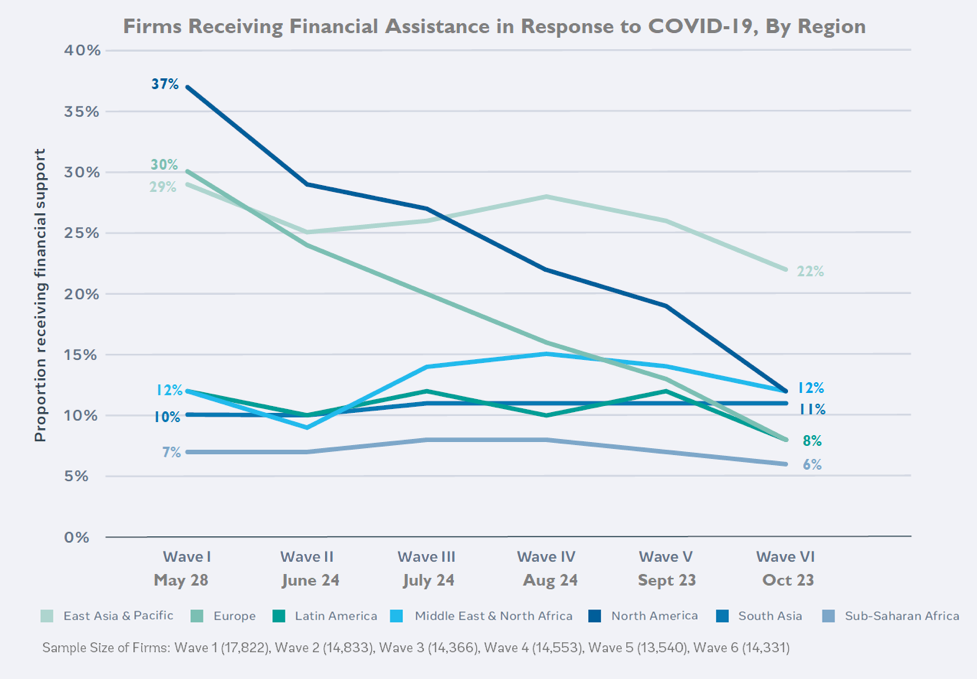

Survey results show large regional disparities in the likelihood of a business to receive financial assistance, as well as gender differences within some regions. The most common types of assistance are grants from the government and unemployment benefits. While many high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have introduced unemployment benefits and expanded social safety nets, the figure below shows that firms sampled in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America are least likely to be receiving any financial assistance during the COVID crisis compared with other regions of the world.

In these regions, the few entrepreneurs that receive financial assistance most commonly cite that funding is received from friends and family rather than from government programs or formal financing sources. To shore up businesses and help protect the many jobs at risk, Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) National Action Plans need to be leveraged to ensure dedicated financing and lending facilities are being introduced to support women entrepreneurs through the crisis period. What Can Be Done?

What Can Be Done?

Paying close attention to the different constraints that men and women face can help design the right policies to move forward post-COVID-19. For example, women entrepreneurs may face higher barriers than men do to access finance, especially in providing collateral for loans, since most assets that lenders accept are typically registered to men. Gender gaps can also extend beyond property to other forms of assets, including financial assets such as bank accounts and savings. Therefore, financing efforts need to ensure funds are being dedicated to directly reach the hands of women.

Targeting methodologies for social protection may have to be adapted to ensure income for groups affected by COVID-19 and for sectors where women are heavily represented (tourism, education, retail, hospitality, and care, etc.). Providing wage subsidies to firms and individuals may help those having to take leave and stay home to care for children during school closings. In addition, redesigning lending products under more concessional conditions, such as lower- or zero-interest loans with a long grace period or longer maturities will better fit the needs of entrepreneurs at this time.

Alleviating financial constraints to women may require innovative technologies and interventions. For example, psychometric tests piloted in Ethiopia have been used to create credit scores and identify creditworthiness, and digital applications to finance (mobile money, digital loans) have brought previously unbanked people to the formal financial sector.

Women in the informal economy need to be supported to access cash transfers or unemployment compensation, especially those who don’t have access to formal banking. Women’s networks such as microfinance groups and savings groups could be leveraged to communicate the existence of benefits. Alongside financial support schemes, trainings that focus on socioemotional skills have been useful to teach proactive behaviors and build resilience for women entrepreneurs. In addition, collecting gender disaggregated data on the economic impact from COVID-19 as well as on the impact of policies that are designed to support women will be important to track progress of the WPS agenda going forward.

COVID-19 has the potential to widen global gender gaps and could leave women even further behind. In order to achieve sustainable peace, economic empowerment of women must be included, and this includes entrepreneurship. Taken together, the data indicate that male- and female-led businesses are impacted differently by lockdown policies and measures of support being put in place to help businesses weather this crisis. Going forward, careful consideration of differential economic impacts by gender of the COVID-19 pandemic will be important to build effective policies to support women.

Markus Goldstein is a lead economist in the Office of the Chief Economist’s Office for Africa at the World Bank, where he runs the Gender Innovation Lab. Paula Gonzalez Martinez is a research analyst in the Gender Innovation Lab at the World Bank. Sreelakshmi Papineni is an economist and research analyst at the World Bank. Joshua Wimpey is a private sector development analyst at the World Bank.

To find out more about the data and the global findings, read the Global State of Small Business report.