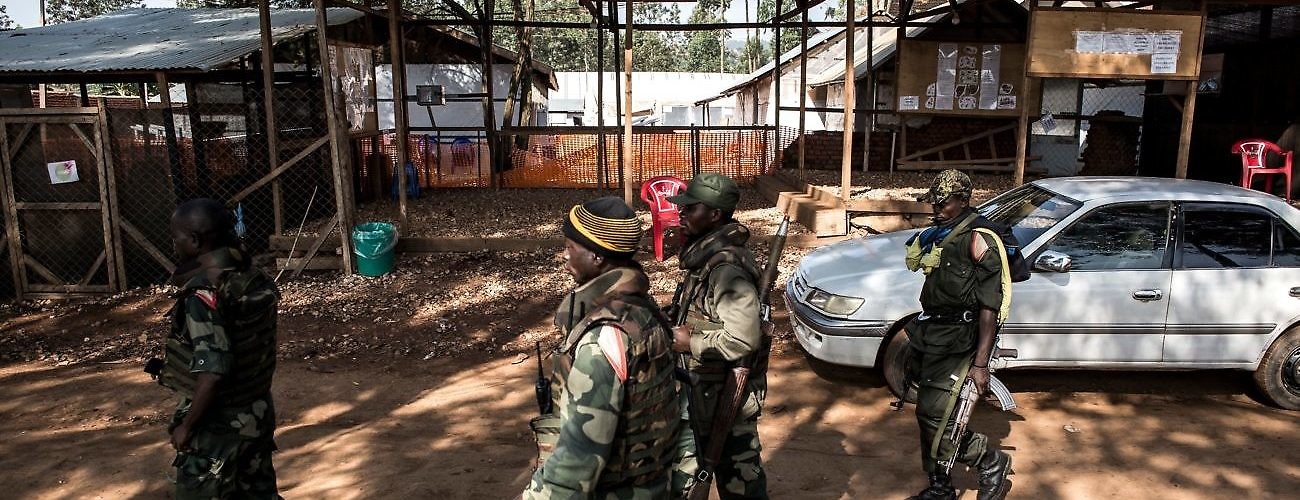

Soldiers from the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) walk outside an Ebola Treatment Center in Butembo after it was attacked on March 9, 2019. (JOHN WESSELS/AFP/Getty Images)

The April 19 murder of a World Health Organization (WHO) official in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has brought to center stage the issue of escalating violence against Ebola responders. The WHO epidemiologist was killed and two others injured when gunmen stormed a hospital in Butembo, located in North Kivu province. Following the incident, doctors and nurses in Butembo threatened to strike unless government security forces did more to protect health workers.

Yet, when assailants set fire to two nearby Ebola treatment centers belonging to the humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in February, MSF took a different approach. They suspended operations and evacuated staff from the hot zone, explaining that the response had become overly militarized and calling for an “urgent change in strategy.”

These actions reveal disagreements over the role of security forces and their relationship with health workers and affected communities in eastern DRC. They also raise questions about the most effective means of safeguarding global health security amid an environment of increasing community hostility and resistance. With the World Health Assembly convening in Geneva this week, the time is ripe for health officials to reflect on current efforts and consider new approaches to the response going forward.

According to a WHO Situation Report on May 22, there have been a total of 1,847 confirmed and probable Ebola cases and 1,223 deaths. The security situation has deteriorated in recent months, interrupting critical response activities such as disease surveillance, contract tracing, treatment, and immunization. Violence persists despite the United Nations Security Council passing resolution 2439 in October, which condemned attacks on Ebola responders and recalled resolution 2286 addressing attacks against medical facilities and personnel.

Few options present themselves for facilitating a more favorable operational environment. The WHO-led international response has relied on armed protection from the UN peacekeeping mission in the DRC, known as MONUSCO. MONUSCO remains a sizable presence in the DRC, with approximately 18,000 uniformed personnel. Following the attacks on the Ebola treatment centers in Butembo and Katwa, MONUSCO “redeployed additional uniformed and civilian personnel to support the security of Ebola response staff,” according to a Security Council meeting on March 18.

However, MONUSCO’s support will not last indefinitely. In March, the Security Council called for an independent strategic review of the mission to articulate a “phased, progressive, and comprehensive exit strategy” following national elections held in December. The Security Council extended the mission until December 2019, but it declined to raise the troop ceiling or adjust mission priorities in view of the outbreak.

Beyond MONUSCO, there appears to be little appetite for foreign military assistance to protect health workers, establish humanitarian corridors, or otherwise scale up response efforts. Despite the successful contributions of bilateral military deployments from the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries in containing the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, military support (assuming the DRC were to request it) is unlikely for many reasons. These include the complex security situation, logistical challenges involved with deploying to central Africa, and increasingly risk-averse Western governments.

Instead, much of the responsibility will fall to the Congolese National Army, known as the FARDC. On May 14, in response to calls for reinforcements in Butembo, DRC Health Minister Oly Ilunga announced a strategic operational plan to strengthen security of Ebola treatment centers in coordination with FARDC, MONUSCO, and the Congolese National Police. It remains to be seen whether Kinshasa can live up to its promise to strengthen security in the outbreak zone.

However, some have questioned whether a more robust security presence would be beneficial, or counterproductive, at this stage. The presence of military troops alongside health workers may be blurring the lines between medical and security personnel, putting civilian staff in the crossfire. According to MSF President Joanne Liu, the heavy reliance on the FARDC and MONUSCO has only increased the perception that health workers are “the enemy.”

The FARDC (as well as segments of MONUSCO) are implicated in hundreds of human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings, sexual exploitation, and torture, especially in North Kivu, according to a December report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. MSF and other humanitarian organizations often refuse to associate with military forces, warning this compromises fundamental humanitarian principles of independence, impartiality, and neutrality.

To complicate matters further, attacks on health workers are increasingly coming from within affected communities or Mai Mai self-defense militias, formed by local leaders ostensibly to protect their interests from outsiders. Rumors and mistrust have taken root, with many residents believing the virus is not real or created for economic gain. Approximately two-thirds of Ebola deaths have occurred outside Ebola treatment centers, meaning many patients were either unable or unwilling to seek treatment.

Evidence in recent weeks suggests that the international community is shifting its focus away from civil-military approaches and towards community-based interventions. In a statement on May 8, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres reiterated that “the full involvement and engagement of local people remains the key to successfully controlling the outbreak.” He alluded to “important shifts in the response now being implemented,” such as changes to WHO vaccination guidelines announced May 7, and he committed to a “collective UN-wide approach.”

While he did not elaborate, this could suggest a greater role in the response going forward for UN agencies other than WHO, such as UNICEF and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA). Their stance is more broadly oriented towards community engagement and the provision of humanitarian aid, instead of narrowly focused on public health and medical interventions. His statement recalls a key transition that occurred during the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, after UN agencies were largely sidelined early on as the WHO asserted itself as UN Health Cluster lead, a dynamic that was later criticized.

Important lessons from other health crises can still inform current efforts. An after-action report published May 9 by the Center for Global Development argued that some of the most scalable interventions during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa transitioned responsibility “away from specialized responders and onto the population at large.” When rigorous case finding, contact tracing, and infection control practices became impractical, the response turned to “wider use of behavioral and community-driven methods” and “engaging credible voices and equipping them with the basic information and tools to adapt to their own community’s setting.”

In his 2016 book, anthropologist Paul Richards documented community-driven responses based on his firsthand accounts of Ebola affected rural villages in Sierra Leone. He described a pattern of “self-directed changes in people’s behavior” structured around local expertise and cultural practices, and he argued that “the humanitarian response to the disease was most effective in those areas where it supported community initiatives already in place.”

Before the window of opportunity closes, the UN, WHO, and international, national, and local partners will need to work together to redouble their efforts to gain the trust of the local population and mobilize community action. Bottom-up and low-profile approaches should adapt to local attitudes, beliefs, and expectations and grant greater autonomy to affected populations in accordance with bioethical principles.

Meanwhile, preparations should continue for the virus’s likely spread outside of the affected provinces, including strengthening disease surveillance, training health workers in appropriate infection control practices, increasing vaccine supplies, and fully funding response efforts. With current approaches reaching their limit in the DRC, the outcome will depend more than ever on the consent and involvement of the affected communities themselves.