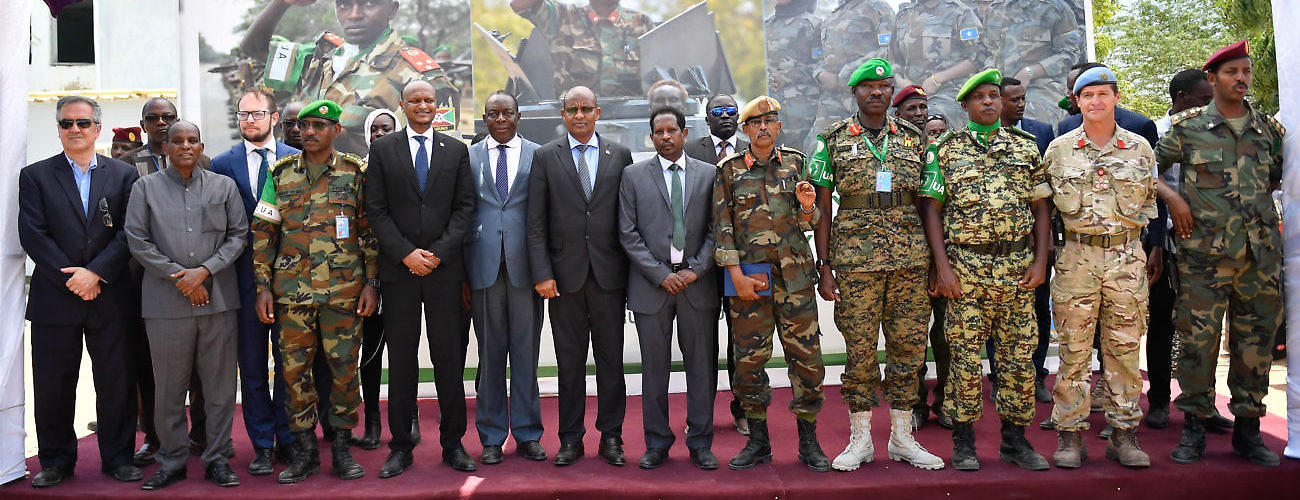

Representatives of the African Union and government of Somalia, along with international partners, pose at the end of a ceremony marking the handover of the Jaalle Siyad Military Academy to the government of Somalia on February 28, 2019. (AMISOM Photo / Ilyas Ahmed)

In February, the African Union (AU) called for the gradual transfer of security responsibilities from the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) to agencies of the federal government of Somalia. While there are positive aspects to this move, similar attempts have been made in the past with limited success.

As part of the current call, AMISOM will hand over its responsibilities in part to the Somali National Armed Forces (SNA), Somali Police Force (SPF), and National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA). Earlier, in December 2017, AMISOM, Somalia’s federal government, and six federal member states agreed to develop a handover plan built on ideas promoted at the May 2017 London Somalia Conference. This conference was part of attempts to achieve the target date of December 2021 for transferring responsibility, as outlined in United Nations Security Council resolution 2431.

At this point, the chances of transferring security responsibilities by then are slim. The primary reason is that any transfer will encompass not only Mogadishu, but all the federal member states in south, central, and western Somalia—places where AMISOM has a presence, but where security institutions must for the most part be built from scratch. Moreover, security provision reflects thirty years of clan politics, entrepreneurial operations, and a trigger-happy approach to decision-making.

Transferring responsibility is also a risky endeavor that could increase existing tensions, as there is no agreement on what the balance of power between the central and federal states should be or how al-Shabaab can be prevented from exploiting the clan-based disputes prompted by the recently-redrawn boundaries. There is also the lure of monetary gain to be had which encourages AMISOM contributors such as Burundi to argue that withdrawal is premature (Burundi gets $18 million quarterly for its troop contribution).

International attention focuses on the political and technical support needed for the transfer, but a more fundamental issue needs to be resolved first: Somalian forces need to change the way they understand their roles and responsibilities, and, critically, how they relate to each other.

An Array of Actors

Security in Somalia is currently provided by the SNA, SPF, and NISA, supported by AMISOM mentors and international advisers, and there are a plethora of challenges these agencies face. Many military and police units have been infiltrated by militia or al-Shabaab sympathizers. Fighting and policing is often carried out by militia and paramilitaries loyal to factional leaders and businessmen, rather than to the SNA or SPF. Government ministries do not operate as institutions, and the federal government lacks the political will to address the challenges.

The environment created by these challenges has resulted in violence on the streets of Somalia. Many of these are gunfights that are caused by arguments over access or by mistaken identity. In 2017, five people were killed in fighting between soldiers and NISA forces after a stand-off at a checkpoint near Mogadishu’s presidential palace. Two months later, nine people were killed when police and NISA forces mistook SNA troops for clan militia. As one police officer said, “accidents happen.” Sometimes no one knows what starts clashes, which can be as violent as those against al-Shabaab. For example, the cause of a fierce gunfight between United Arab Emirates-trained SNA soldiers and NISA troops supported by the United States at a traffic junction on March 21, 2018 was never identified.

It does not help that the roles, remit, and membership of the SNA, SPF, and NISA are fluid. But this is a natural result given that over many years Somalian society has been shaped by civil war, distrust, legal pluralism, and identity politics, and al-Shabaab is an integral part of society, rather than a separate organization.

In practice, clan affiliation offers the most reliable security available. This is accentuated in Mogadishu where the Hawiye clan dominates the military and business and are a significant proportion of the population, while the Darod influences the government. The SPF’s elite counter-terrorism units tolerate a mix of clans, but this is not true for the SPF as a whole.

The frequency of incidents and the social reality in Somalia suggests that for AMISOM’s exit plans to be achievable, the expectations of Somalian government capacity need to be modified. No amount of training or logistical support will ensure that today’s SNA and SPF are able to fully take over security responsibilities in 2021.

NISA and SPF’s Important Role

Focusing on transferring responsibility also diverts attention from a second important issue: the way in which Somalia is to be policed. AMISOM’s exit plans may depend on the SNA, but the resilience of al-Shabaab and the volatility of Somalia’s society mean that the SPF and NISA are of longer-term significance.

The best indicator of how policing will develop is to be found in the federal government’s plan to reorganize the SPF and NISA. For now, the SPF remains an ineffective organization that trades on its position as heir to the internationally-respected SPF of the 1960s. But it also represents the best hope for a politically legitimate and development-oriented security sector. For its part, NISA is the most effective and best-connected (albeit arguably constitutionally illegitimate) force operating today. It is also best placed to profit from the jockeying for position that will inevitably take place in the run-up to transfer.

AMISOM and donors speak about Somalia developing a professional police force that provides services to the community. So does the federal government. But developments in September 2018, when more than 1,700 NISA officers were transferred into the SPF, suggest that this will not be straightforward.

Formally, the NISA officers—who are known interchangeably as agents, detectives, or troops— to be transferred will leave behind their responsibilities for covert operations and intelligence collection in order to contribute to the SPF’s task of maintaining law and order. Nevertheless, NISA is to retain responsibility for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforcement and, critically, national security and military and foreign policy objectives. This is justified in terms of eliminating functional overlap, which may indeed do this. One outcome will certainly be an edge in community policing.

Moving Forward

Transferring full security responsibilities by December 2021 is ultimately unlikely given these circumstances. The probable outcome is that AMISOM and the international community will provide the technical and financial support and political cover needed for transfer to take place sometime in the early 2020s.

NISA is best placed to help achieve this target. A slight improvement can be expected in the SPF and the SNA is unlikely to change in the intervening months. Power struggles will also continue to shape security provision, just as they did in July 2018, when the office of NISA’s deputy director was raided, and in October 2018, when disorganized intelligence gathering allowed al-Shabaab to use a truck bomb that killed more than 300.

For now, it is business as usual. Transfer will eventually happen even though the societal and political shifts required for Somalian security agencies to change the way they operate, let alone to carry forward AMISOM’s responsibilities, singly or jointly, will not happen. Importantly, any transfer needs to be palatable both to donors and to Somalians because, ultimately, security provision has to be locally accepted and driven if it is to be sustainable.

Dr. Alice Hills is a visiting professor of conflict studies at Durham University and at the University of Leeds.