A women cast her ballot for the general elections, on March 7, 2018 at a polling station in Freetown, Sierra Leone. (ISSOUF SANOGO/AFP/Getty Images)

Sierra Leone’s fifth postwar election maintains the two term limit for the presidency, underscoring what hopefully is a major new trend in Africa in which rotation in power at the helm of government is the norm. At the same time the elections underscores the ethnic and regional divide which has characterized the country’s politics for decades. On March 27, the All People’s Congress (APC) candidate Samura Kamara, garnering major support from Temne voters in the north, will face off against Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP)’s candidate Julius Maada Bio, who enjoyed strong support among the Mende majority in the south, in the second and final electoral round.

Sixteen candidates competed in the March 7 election, but none of them obtained 55% of the vote. Each of the two major parties had close to 43%, while former United Nations official Kandeh Yumkella—who had formed a new third party— gained little traction and came in a distant third. Outgoing President Ernest Bai Koroma had served two terms and hence was not allowed to run again.

This election has again highlighted both the challenges and opportunities facing Sierra Leone. This small West African nation, a former British colony which gained independence in 1961, has had a difficult 57 year history. It suffered initially from corrupt, inept, or at best well-intentioned but ill-equipped leadership, and then became embroiled in a protracted regional civil war. While it is unlikely that war will break out again, the country faces major difficulties in attracting significant investment for development and creating economic opportunities for its growing youth population.

The significant loss of its most educated populations during the era of Siaka Stevens meant that recent governments have had to struggle to find qualified leaders and civil servants to run ministries. Moreover, the protracted civil and regional war spilling over from Liberia between 1991 and 2001 cost tens of thousands of lives and the destruction of an already fragile infrastructure. Rebuilding that infrastructure has attracted a large official and private Chinese presence—as throughout West Africa—which further threatens to weaken the country’s political and economic independence.

The Road to Now

The cross-border regional civil war in neighboring Liberia precipitated by a power struggle between Charles Taylor—now serving a 50 year sentence in a UK prison—and his numerous competitors killed and maimed thousands of young Sierra Leonean men and women over seven years, mainly in the countryside. After peace agreements signed in Abidjan, and several years later in Lomé, the war ultimately ended with the intervention of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), mainly Nigerian troops, followed by the deployment of the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), a major peacekeeping operation in support of the government. Sankoh served briefly as vice president but after a few months in office tried to topple the new government. He was arrested and subsequently died in Pademba Road prison while the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) was effectively disbanded. Since then, Sierra Leone’s governments have made halting progress, hindered by extensive corruption and political infighting.

In 2007, Sierra Leone came on the agenda of the UN Peacebuilding Commission, established two years earlier to assist countries emerging from protracted conflict to recover and rebuild their institutions. The past 11 years have seen a slow economic recovery assisted by investments from the World Bank and UN. The country has also benefitted from the return of many Sierra Leoneans from England and the US in the past decade. It has also been the focus of political engagement by ECOWAS and the African Union.

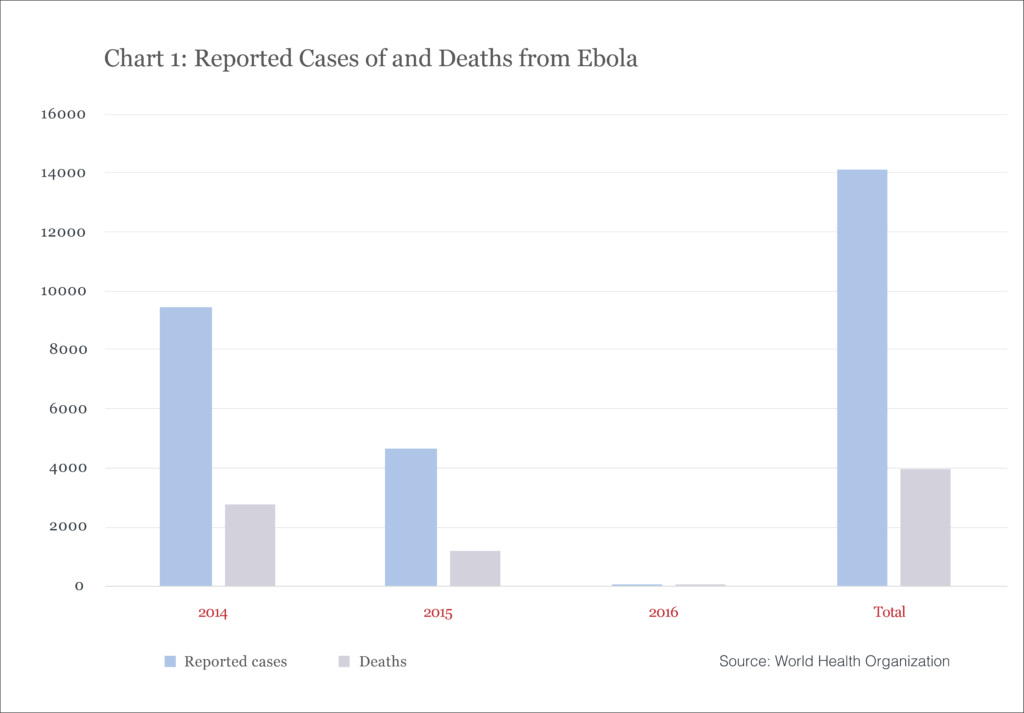

Sierra Leone made limited progress until 2014 when a major health crisis erupted in the form of the Ebola epidemic. The government was completely unprepared for this major new killer; the spread of Ebola, as well as the continuation of HIV-AIDS and malaria (see chart one) quickly overwhelmed the country’s fragile health sector and economy. Since then these concomitant crises have cost more than 8,000 lives, abruptly stopped the country’s economic development, and severely hindered its postwar recovery. The challenge for the incoming government is to address all these deficits, to restore public and international confidence, and to promote meaningful economic development. These are the prerequisites to enable the new generation of Sierra Leoneans to contribute to the strengthening its economic future. The winner of the March 27 second round will have much to do to move the country ahead.

The Impact of Multiple Health Crises

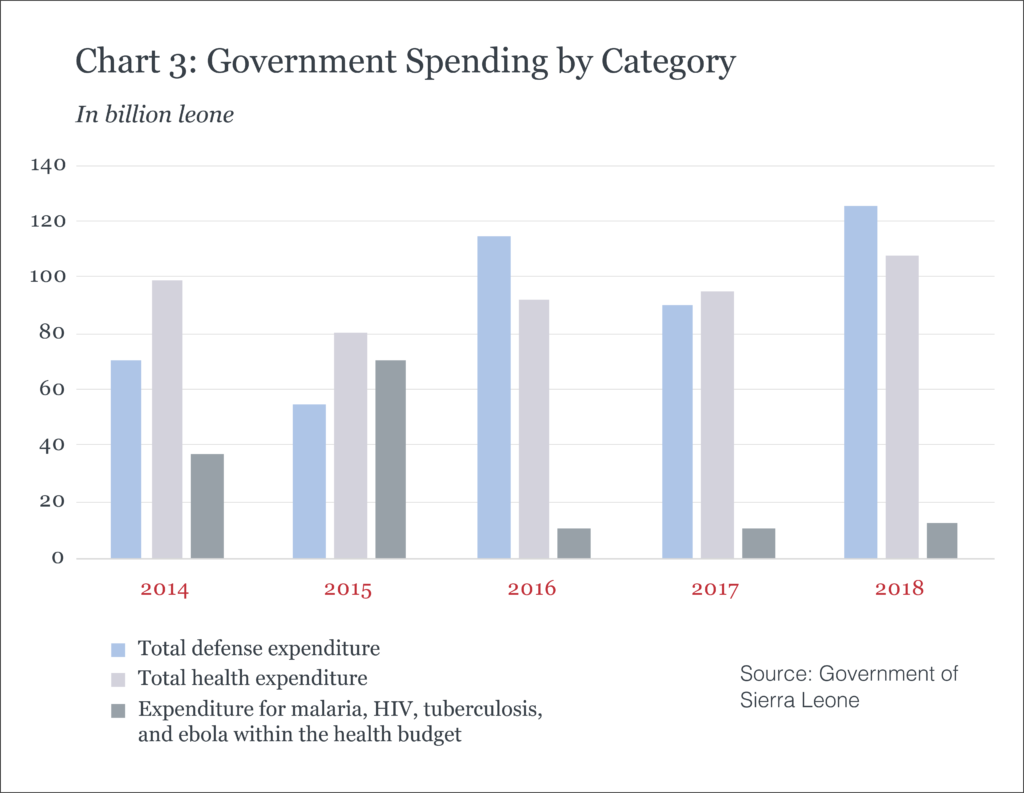

As shown in the accompanying charts the Ebola, malaria, and HIV-AIDS crises have laid bare the country’s lack of preparedness. Unless the new government takes action this will continue in the near future.

During the Ebola crisis the Sierra Leonean government was completely unprepared. The country had 0.024 doctors per 1000 people and the government was struggling to find well-trained government workers for its administration. With 14,124 cases, Sierra Leone became the epicenter of the crisis in West Africa; 3,956 died in the span of two years. A weak healthcare system, a shortage of health professionals, high illiteracy rates, and traditional practices—particularly those of handling bodies before burial—contributed to the uncontrolled spread of the epidemic.

International aid organizations directed millions of dollars to try to solve the problem but widespread corruption thwarted a portion of these efforts. Sierra Leone ranks 123rd in Transparency International’s 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index; corruption scandals repeatedly tarnished the APC government performance. In a recent statement, the Red Cross admitted a loss of $2 million during the Ebola crisis due to collusion of their staff with local bank workers, and non-compliance in procurement practices.

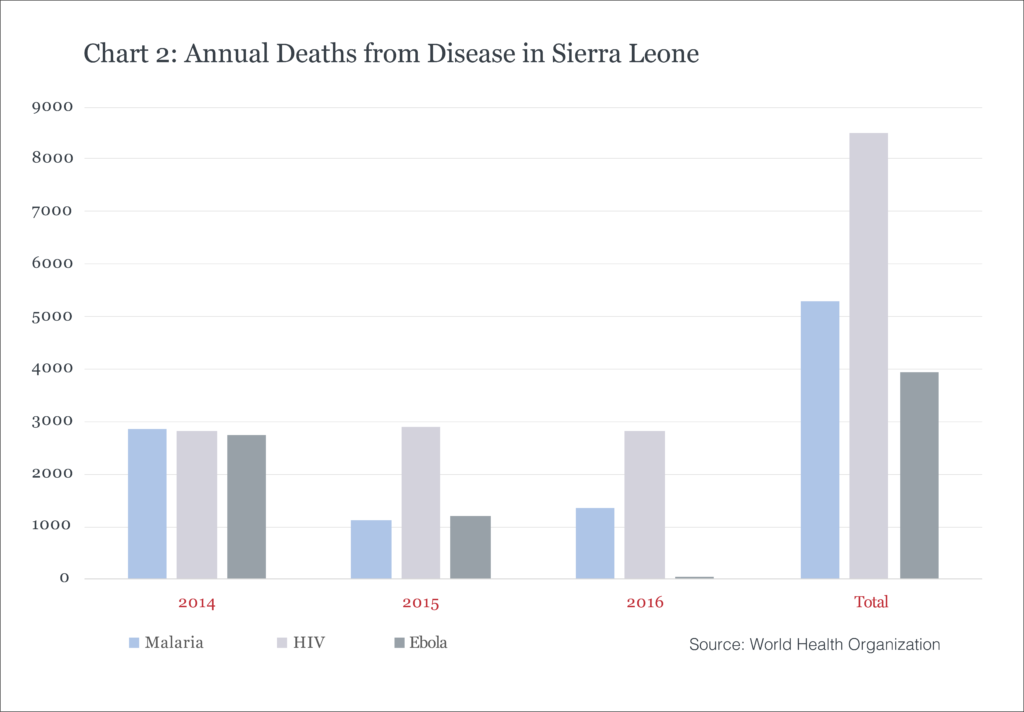

In March 2016, the World Health Organization, in a joint statement with the Sierra Leone government, declared the end of the epidemic (see chart two). During the crisis and in its aftermath a number of plans were set up to ensure that a similar crisis does not recur. The UK has funded the Maintaining Resilient Zero for Ebola program investing £29 million until December 2017—focusing on infectious disease control health policy, administrative management, and paying for the Ministry of Health administration. Furthermore, the government set up an Emergency Operation Center, a Fast Response Team, and a plan to support the survivors which includes providing them with free healthcare. Health workers are receiving training on Infection Prevention and Control Protocols, and laboratory capacities have improved. The training and equipment that health and laboratory professionals received during the Ebola outbreak are now being used to fight diseases such as tuberculosis, HIV, and malaria, for which yearly death tolls have skyrocketed.[1]

The Uncertain Future

In looking ahead, the government has designed a “National Ebola Recovery Strategy for Sierra Leone,” setting up the priorities to recover from the crisis. The priorities outlined by the plan are to restore the health system, improve access to water, strengthen education, and support the agriculture, transportation, and financial sectors to boost economic development.

Are these strategies enough? Are they going to make Sierra Leone more resilient to similar catastrophes? Beyond the strengthening of the healthcare system the country faces other equally sizeable challenges. There have been severe floods and mudslides in the last decade, which have affected more than 200,000 people in the poorest sections of Freetown, and in one month took over 1,000 lives.

The country suffers equally devastating droughts during its dry season. The government lacks proper water management systems to supply water for human consumption and to water crops. While there are plans to rehabilitate water wells and boreholes, some argue that the construction is not sustainable or cost effective for villagers to maintain in the long run.

In sum, improved resilience will depend in large part on the performance of the incoming government. Will the next government continue with the plans that were established during Koroma’s two terms in office or develop new strategies from scratch? In either case it will take strong leadership to put an end to the corruption that has afflicted the economy and enable the government to design a sensible strategy to make the best use of international aid programs.

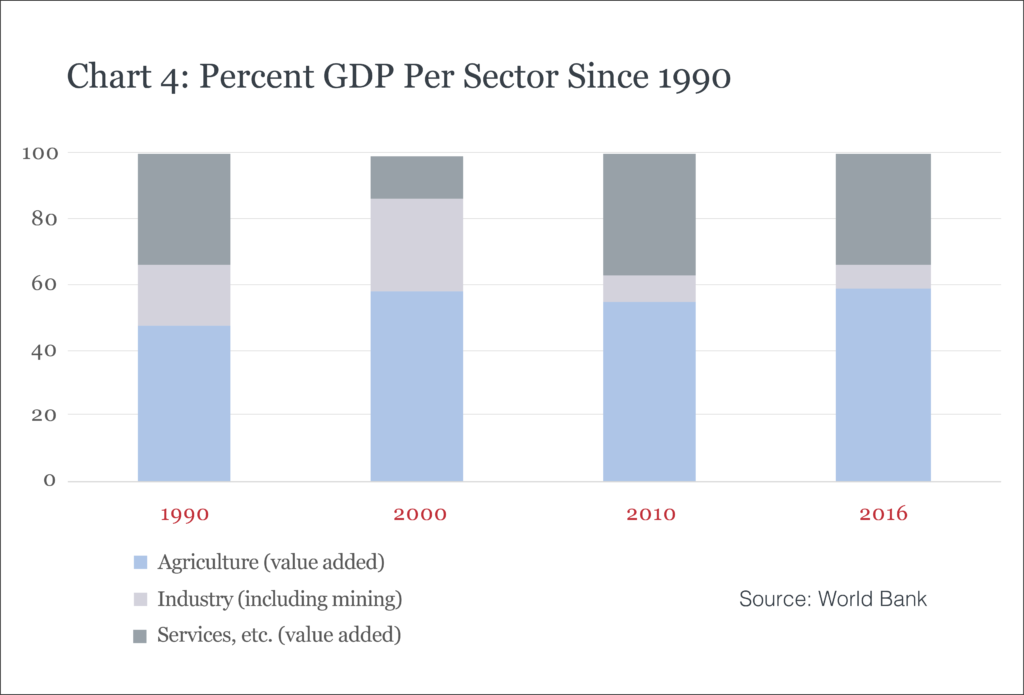

Forward planning to boost the economy and its infrastructures, and strategies to reduce the levels of corruption could pave the way for development. Some have pointed at the potential of the agricultural sector—especially cocoa and coffee—and the mining sector as potential panaceas to the financial struggles. Agriculture provides the majority of the country’s GDP but the industry sector, including the mining sector, used to constitute 22% of the GDP in 2013 immediately before the Ebola crisis. The mining sector then plummeted in 2014 due to the Ebola crisis and the collapse of iron prices, but with the country’s recovery the sector is expected to grow robustly in the upcoming years. Even though these are the prospects, the newly elected government will have a pivotal role in setting up the right policies to ensure a smooth and steady development of the country and to prevent any future crisis that could prevent this still recovering country from escaping half a century of struggle.

John Hirsch is a Senior Adviser at IPI and a former US ambassador to Sierra Leone. Lidia Cano is a researcher and consultant specializing in peace-building and natural resources governance. She is a Fulbright Scholar and has provided research, inferential analysis and advised governments, international organizations, and the private sector.

[1] In 2013, there were more deaths from malaria than from Ebola in the entire span of the crisis. Similar figures can be found for tuberculosis, with 3,300 deaths in 2015, and HIV, with 2,800 deaths in 2016. The Global Fund has so far committed $261 million dollars specifically to fight these diseases and strengthen the health care system in the country. The grants include funding to develop a “comprehensive national response to HIV/AIDS”, a “National Malaria Control Program,” or a project to “Strengthen the Implementation of DOTS Activities” amongst others.