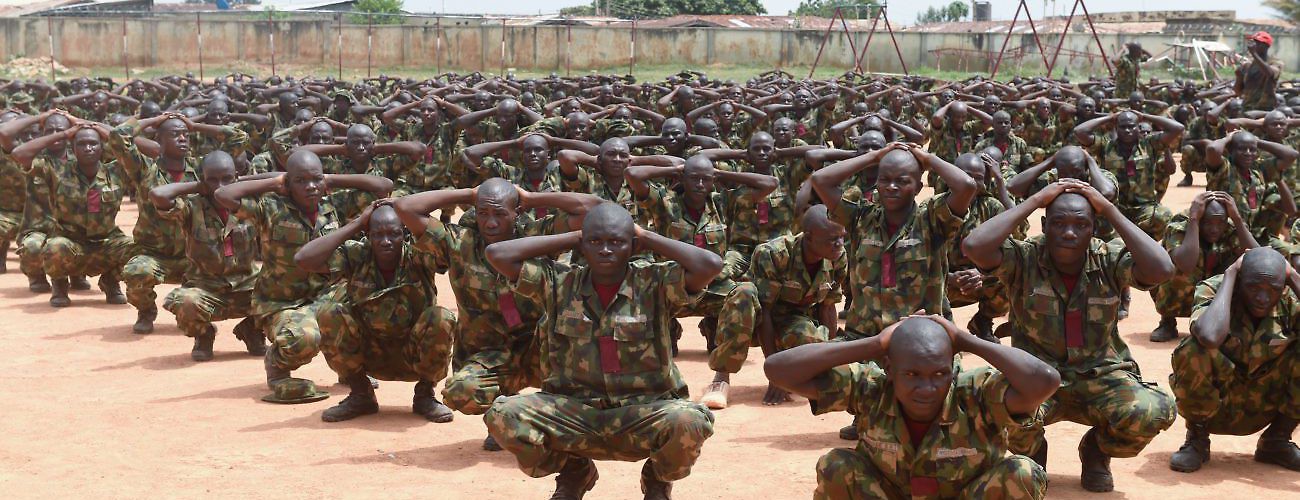

Recruits undergo training at a Nigerian Army Depot headquarters in north central Nigeria, on October 5, 2017. The Nigerian army train recruits to tackle the threat of Boko Haram in the north east of Nigeria. (PIUS UTOMI EKPEI/AFP/Getty Images)

In recent months, Boko Haram has attacked rural military bases and convoys in the northeastern part of Nigeria and in surrounding countries, acquiring weapons in the process. Since spring 2015, when regional militaries chased most of its members back underground, the sect had been focused on survival and terrorism. While the group is far from their high point of 2014-2015, when they controlled a territory estimated at 20,000 square miles, these raids show a new strategic acumen.

Many of these raids are reportedly carried out by a breakaway faction led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi, rather than the movement’s longtime leader Abubakar Shekau. Al-Barnawi’s faction is formally aligned with ISIS, but their recruitment base and area of operations is highly localized to northeastern Nigeria and the surrounding region. What makes al-Barnawi’s group dangerous is not necessarily their ties to the Islamic State, but rather their new strategy.

Al-Barnawi’s raids on military bases have been a pattern since his group’s break with Shekau in the summer of 2016. The group sometimes attacks the same site repeatedly, as was the case with assaults on a base in the village of Kamuya in December 2016, January 2017, and July 2017. The attacks serve multiple purposes simultaneously. By raiding the military’s supplies, Boko Haram can replenish its weapons and ammunition. Their hauls can be large: a raid on a military base in Marte a few weeks ago in October yielded a “cache of arms and vehicles, including seven rocket-propelled grenade launchers and 200 rounds of ammunition.” Another October assault on the village of Sasawa netted Boko Haram “two pick-up trucks equipped with anti-aircraft guns.” Often, by raiding the host village as well, the fighters also replenish their food stocks, generating momentum for the next raid.

At the same time, Boko Haram keeps the military partly on the defensive. When attacking rural outposts, they often destroy military infrastructure, for example by burning and razing barracks, as in the raids on Kamuya. In this way, Boko Haram seeks to ensure that any energy the military could be spending on offensive operations, manhunts, or consolidation efforts are instead diverted to reconstruction. Or, in the best case scenario for Boko Haram, the military will quietly cede some territory to the sect’s influence, giving it footholds from which to start extracting more resources from local communities and gaining greater freedom of movement.

Boko Haram is also trying to frighten Nigerian soldiers and is, to some extent, succeeding. Throughout the conflict, soldiers have sometimes been reluctant to engage Boko Haram in battle, especially in remote areas where they fear being easy prey for the jihadists, who know the terrain better. Through its rural raids, Boko Haram is making vividly clear to soldiers that the countryside is dangerous—the raid on Sasawa claimed an estimated fifteen lives. Soldiers’ sense of insecurity is reinforced by Boko Haram’s attacks on their convoys. Also in October, soldiers repelled fighters who were targeting a battalion commander’s convoy in northeast Nigeria but lost at least three of their own in the process. If even commanding officers are vulnerable, then the enlisted men must be keenly aware of the dangers.

These dynamics can reinforce a tendency for the military—as often happens in wars against rural insurgencies—to hang back in cities. The more the military abandons the countryside to jihadists, however, the stronger Boko Haram can grow.

Despite its recent advances, Boko Haram also faces its own challenges. Al-Barnawi’s group ostensibly broke with Shekau in order to bring focus back to the insurgency. Whereas Shekau labels virtually all outsiders as unbelievers and treats them as targets deserving violence, al-Barnawi promised to concentrate on fighting the Nigerian state and the country’s Christians. Theoretically, then, the danger of al-Barnawi’s program is that he may find a way to generate more popular support than Shekau currently enjoys.

In practice, however, raiding villages, stealing villagers’ food, and killing soldiers will inevitably antagonize much of the rural population. Al-Barnawi faces conflicting incentives: keep his men supplied and content, but also try to build goodwill with locals. For now, clearly his men come first; the test will be when and if his group becomes strong enough to truly control territory, at which point they will face the question of how to rule. During Shekau’s era as head of an unstable, conflict-riven proto-state in 2014-2015, Boko Haram’s rule was highly predatory—they provided almost no services and instituted a crude form of sharia, while allegedly murdering civilians and even their own fighters.

Shekau also continues to complicate al-Barnawi’s ambitions. Seemingly deeply isolated in rural Borno, Shekau’s group nevertheless is able to stage violence. On the one hand, then, Shekau’s violence competes with al-Barnawi’s, which in turn puts them in competition for recruits, supplies, turf, and attention. On the other hand, Shekau’s violence blurs the picture and undermines any branding effort al-Barnawi may attempt—to villagers, after all, it is not necessarily always clear whether it is Shekau’s Boko Haram or al-Barnawi’s “Islamic State West Africa Province” that is stealing their food and setting fires. Al-Barnawi’s political project, then, faces several obstacles.

Faring worst of all, as usual, are civilians. Objects of predation for most of Boko Haram and, tragically, often objects of suspicion for soldiers, the civilian population of northeastern Nigeria and the Lake Chad Basin faces continued violence and a dramatic humanitarian crisis. Boko Haram’s violence against the military in rural areas impedes the delivery of services and relief there, which sets the stage for further suffering. Many people’s fates depend, then, on whether the military can definitively claim control of the countryside.