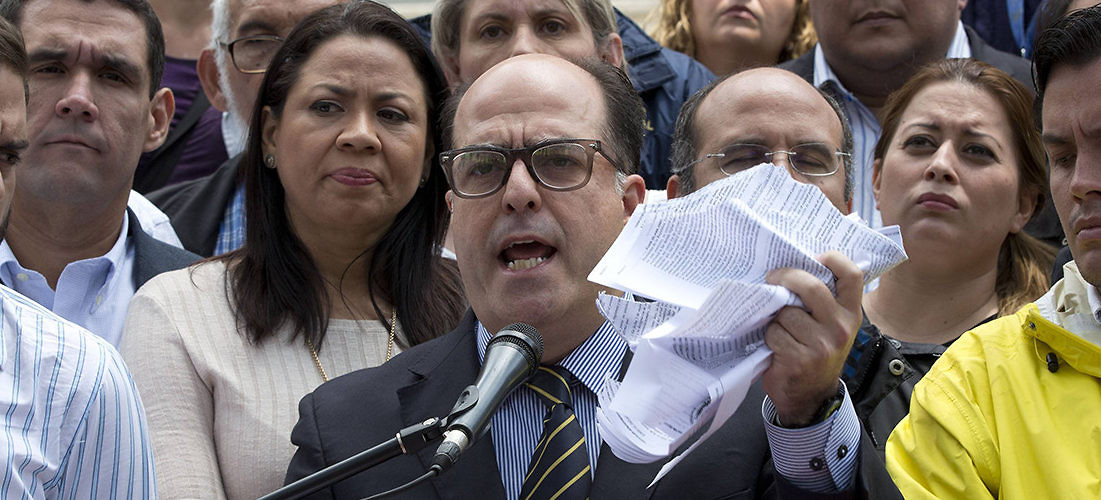

National Assembly President Julio Borges displays ripped copies of documents ruling that the Supreme Court can assume parliamentary responsibilities. Caracas, Venezuela, March 30, 2017. (Ariana Cubillos/Venezuela)

In late March, the Venezuelan Supreme Court usurped the functions of the National Assembly—the country’s legislative body—and stripped deputies from opposition parties of their parliamentary immunity. In practice, the rulings simply gave official recognition to a de facto arrangement—the court had already declared the opposition-controlled Assembly in contempt in January 2016 and President Nicolás Maduro and his executive branch have been using the order to govern without the parliament ever since.

Symbolically, however, the rulings signaled an important shift in the political situation and, perhaps, an opening to begin a significant push for regime change. Even after the Supreme Court slightly altered the rulings, the move reenergized popular demonstrations against the government.

Even though the Chavista government had become increasingly more authoritarian, the move against the National Assembly was the first time the regime had so overtly attacked democratic principles. Last year, the Chavista-controlled Electoral Council suspended a referendum on recalling Maduro and refused to call for regional elections. These decisions, though certainly undemocratic in nature, were still able to be painted by the government as nothing more than “irregularities.” Stripping congress from its authority, however, was a new low. It was a blatant attack against democratic institutions and brought back memories of past South American authoritarian leaders such as Alberto Fujimori in Perú.

In the midst of a historically severe economic crisis and overall discontent with the government, the overt attack against democratic institutions was the push those who oppose the government needed to attract significant support domestically and abroad. Immediately after news of the court rulings broke, several countries and institutions condemned the “self-coup.” Regional trade bloc Mercosur produced a resolution calling the Venezuelan government to restore constitutional powers, as did the Organization of American States. The significance of these resolutions cannot be overstated. Despite an aggressive anti-Maduro campaign, up until last week the opposition had been unable to draw significant international support. This is the first time in a decade that regional organizations have strongly condemned the Chavista government.

Inside Venezuela, the Supreme Court’s decision also had important repercussions. First, and most importantly, it created, or brought to light, dissent within the Chavista ranks. General-Attorney Luisa Ortega, who until now had been loyal to the regime, publicly criticized the decision, defined it as unconstitutional, and called on the government to walk it back. It is unclear what will happen to Ortega in light of her news conference. Nonetheless, the fact that she (and perhaps others silently inside the governing coalition) were willing to break ranks highlights important spaces that the opposition could potentially exploit to push for democratic change.

This flows onto the second outcome: Although the decision directly damaged the opposition coalition, the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), it also provided it with much-needed oxygen. The failure of the recall referendum against Maduro in October of last year left the opposition damaged and somewhat dormant. There were rumors of divisions and internal fights, Venezuelans seemed increasingly disenchanted with their political leaders, and support for the coalition decreased. The Supreme Court rulings changed that. They allowed the MUD to rally around the flag, and gave it a concrete and achievable goal on which to concentrate.

Despite these developments, the government is yet to show any desire to make significant changes. On March 31, Maduro called the National Security Council to study the situation. On the Council’s orders, the Supreme Court slightly revised its rulings. The modifications were, however, insufficient to address the criticisms. Moreover, in the past few days, the government has brutally repressed peaceful protests against it. There are reports of government-affiliated gangs using firepower against protesters and National Guard officers throwing tear gas from helicopters. At the time of writing, two protesters have been killed, at least 50 people have been injured, and 291 have been detained. The government also banned Henrique Capriles—an opposition leader and former presidential candidate—from running for office for 15 years.

What happens next is still uncertain. Despite the repression, or perhaps emboldened by it, the opposition seems determined to keep pressing the government. Its members have been organizing pacific demonstrations on every second day for more than a week. The immediate goal is to have Maduro remove the justices who signed the unconstitutional rulings and schedule the regional elections due to occur last year. The opposition has successfully redefined the narrative and gained the attention of the outside world; it is thus an opportune time to keep up the pressure.

Whether the government will yield is an entirely different matter. Maduro and most of his inner circle seem entrenched in their positions. It also remains uncertain why, given that they were benefiting from the status quo, the Supreme Court tried to dismiss the Legislative Assembly in the first place. What did the government expect, or does it still expect, to get out of the move?

The extent to which there has been a rupture inside Chavismo will become clearer in time. Ortega has not said anything since opposing the Supreme Court rulings and there has not been any other visible mass movement inside the government. More significantly, there is yet to be any positive sign from Venezuela’s armed forces toward recent events. The opposition needs to win over some of its members if it wishes to force Maduro’s hand. Up to this point the military has benefited greatly from the regime and is the group that stands to lose the most with any change of government.

Laura Gamboa-Gutiérrez is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Utah State University.