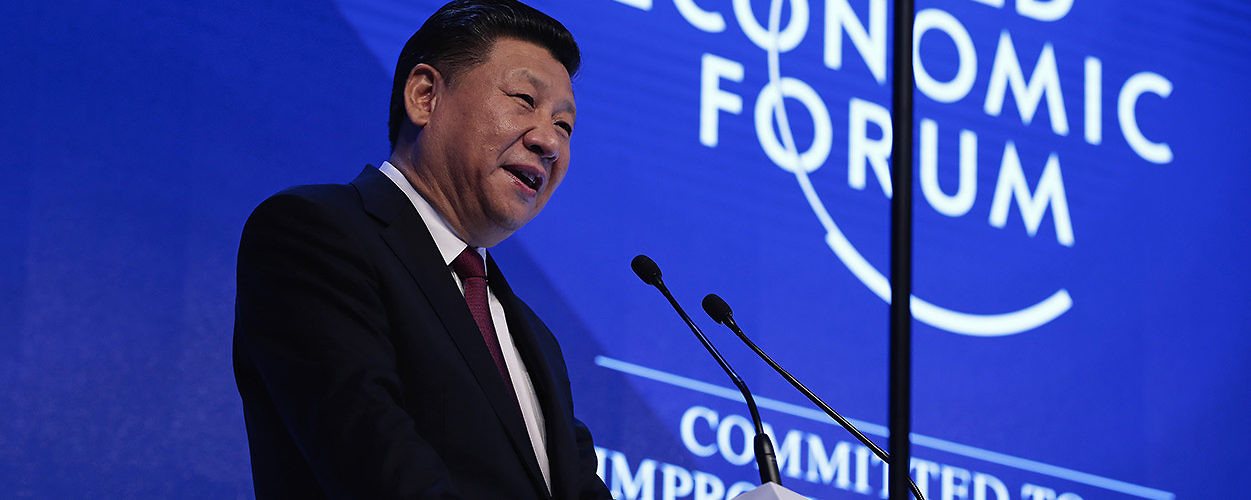

Chinese President Xi Jinping addresses this year's World Economic Forum. Davos, Switzerland, January 17, 2017. (Jason Alden/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

United States President Donald Trump’s eventual acceptance of China’s “One China” policy earlier this month was considered a win by supporters of his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping. While this would imply Trump lost out in the equation, that distinction should go to frustrated supporters of Taiwanese sovereignty alone. The decision otherwise protected a status quo between the world’s two largest powers that is often uneasy but at least provides room for growth. Ensuring the US and China can continue to work together on areas of mutual interest is thus a win for both countries.

Trump had argued shortly after taking office that he didn’t see why the US should be bound by One China, “unless we make a deal with China” on issues such as trade. In taking a step back from that position, he acknowledged, for better or worse, that acceptance of the policy was the “political foundation for China-US relations,” as Beijing’s foreign policy spokesperson Lu Kang said after Trump’s acquiescence. While the full motivations for the about-face might take some time to emerge, Trump acknowledged, quite correctly, that China has now reached a sufficient level of economic, military, and political strength that Washington must pay the entry fee for dialogue, or commit to a potentially perilous course of escalating tensions.

Signs that the new White House increasingly recognizes this can also be found in its lack of action on China’s supposed trade violations—as a campaigner, Trump had promised to label the country a currency manipulator on his first day in office, and to place a 45% retaliatory tariff on imports to the US. The failure to make good on those pledges to date stands in stark contrast to his speed in honoring pledges to begin repealing the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act and implement curbs on travel to the US from supposed Islamic terrorism hot spots.

While the new US administration may not have targeted China directly, it has certainly taken trade-related steps that may change the balance of international economic and political power. Unfortunately for Washington, these seem to have played more into Beijing’s hands than its own. Trump’s effective ending of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), for example, was done for ostensibly economic reasons alone. It thus ignores the fact that the Obama administration constructed it as much for the political rationale of strengthening ties with key US allies and cementing its engagement in the region.

There is a good case to be made that Barack Obama’s own reasoning here was flawed, and that engagement with China as one of the dual engines of the regional and global economy—including supporting Beijing’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank—was a better long-term strategy. Nevertheless, the new American administration is now in a position of having no proposed means of either countering China or engaging with it more closely. In the meantime, the TPP vacuum could be filled by the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership deal, which China is negotiating with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and other countries.

Beijing has also stepped into the breach left by Washington in terms of proselytizing for free trade and globalization more broadly. At this year’s World Economic Forum, Xi offered a passionate defense of international economic liberalization and anti-protectionism that recalled former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. Despite what some see as the superficial nature of these comments, in light of China’s continuing mercantilism, there are already signs of success: European Union leaders have reportedly agreed to bring forward a summit with China that focuses on trade and other cooperation.

A similar dynamic of Chinese leadership supplanting the US role appears to be playing out in the climate change realm. Here, Xi and other senior Chinese officials have made strong statements about maintaining the trajectory set by the United Nations-brokered Paris agreement of late 2015. This commitment comes at the same time that Trump is promoting new widespread fossil fuel development and has appointed cabinet members, such as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Environmental Protection Agency head Scott Pruitt, who promise to break from Obama era commitments.

The long timeframes and indirect nature of many of the repercussions of abandoning climate cooperation may ultimately be insufficient to convince the new US administration of the need to maintain a strong Chinese relationship. There are, nonetheless, many areas of pressing and direct concern where it will continue to be necessary. North Korean missiles, first and foremost, now look increasingly capable of targeting not only US allies such as Japan and South Korea but American military bases including Guam. A senior analyst from the Center for Strategic and International Studies has even warned that Pyongyang “may already have the pieces” of an intercontinental ballistic missile that could reach the US mainland.

While Chinese officials were quick to condemn North Korea’s latest aggression, they have long been unwilling to place more pressure on its leader Kim Jong-un to scale back his assertiveness. Beijing also reacted poorly to Washington and Seoul’s decision of late last year to deploy a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system to South Korea, to protect against the North’s aggression; along with Moscow, it fears that the anti-missile system is at least partly targeted at its own strategic security interests. Overcoming these difficulties will be challenging but not impossible.

Rather than abandon the nuclear arrangement that the Obama administration and other governments struck with Iran last year, the new White House could focus on pursuing a similar outcome that limits North Korea’s program—if negotiating with Pyongyang directly proves too difficult, it could at least find common ground with Beijing. For its part, China appears to favor the former approach and may have just laid the groundwork for Washington to pursue it, with the announcement this past weekend that it would cease coal imports from its troublesome neighbor in line with long-running American requests.

Further afield, the South China Sea remains a powder keg of potential conflict. Once again, this is not an issue of mere symbolic American value, or one that involves commitment to Washington’s allies alone. The 1.4 million-square mile expanse is, according to Robert D. Kaplan, the “mass of connective economic tissue where global sea routes coalesce,” while its concentration of petroleum is, by some estimates, second only to that of the Persian Gulf. The region’s continued stability is therefore of vital importance to the US as a global trade and economic powerhouse, independent of considerations of other countries.

The possibility of managing the South China Sea dispute in a careful and considered way appeared slim when Tillerson said during his Senate confirmation hearing that Washington would have to “send China a clear signal that, first, the island-building stops, and, second, your access to those islands also is not going to be allowed.” He later tempered those sentiments, however, and US Defense Secretary James Mattis also played down the need for major military moves in the region in the near future.

Yet it remains to be seen whether the Trump administration will truly accept the new normal suggested by former US Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert, who said in January that “it is too late to reverse or undo occupancy, without risking a conflict. Our future strategy should assume these facilities are in place and active, and pursue limiting their use.” On the contrary, Trump’s chief strategist—and National Security Council member—Steve Bannon has spoken of the inevitability of war over the South China Sea dispute within the next five to 10 years. As a RAND Corporation report warned last year, conflict between the US and China sparked by a disagreement such as this would be destructive, prolonged, and inconclusive for both parties.

Just as the initial impasse over One China seemed to be overcome by the Trump administration’s apparent realization of the degree to which China’s growing strength constrains White House decision-making, it seems likely that factors outside the new administration’s control will continue to dictate much of its policy toward America’s fellow great power. Nonetheless, the dangers of leaving this to chance are too great. They will need to remain foremost in the minds of those capable of influencing policy in each country, and in governments everywhere that engage with Beijing and Washington.