A participant in UN Women-led training for internally displaced persons. Juba, South Sudan, April 20, 2016. (JC McIlwaine/UN Photo)

Across peace and development initiatives, the exclusion of women comes at a high cost. Without women’s equal participation, peace agreements are more fragile, peacekeeping missions are less credible and safe, and economies are less prosperous.

A recent report from the United Nations Development Programme adds to the growing body of evidence on the very real costs of exclusion and the positive impact of women’s participation. UNDP’s second Africa Human Development Report, Accelerating Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Africa, serves up “a stark reminder that gender equality is a critical enabler of all development.”

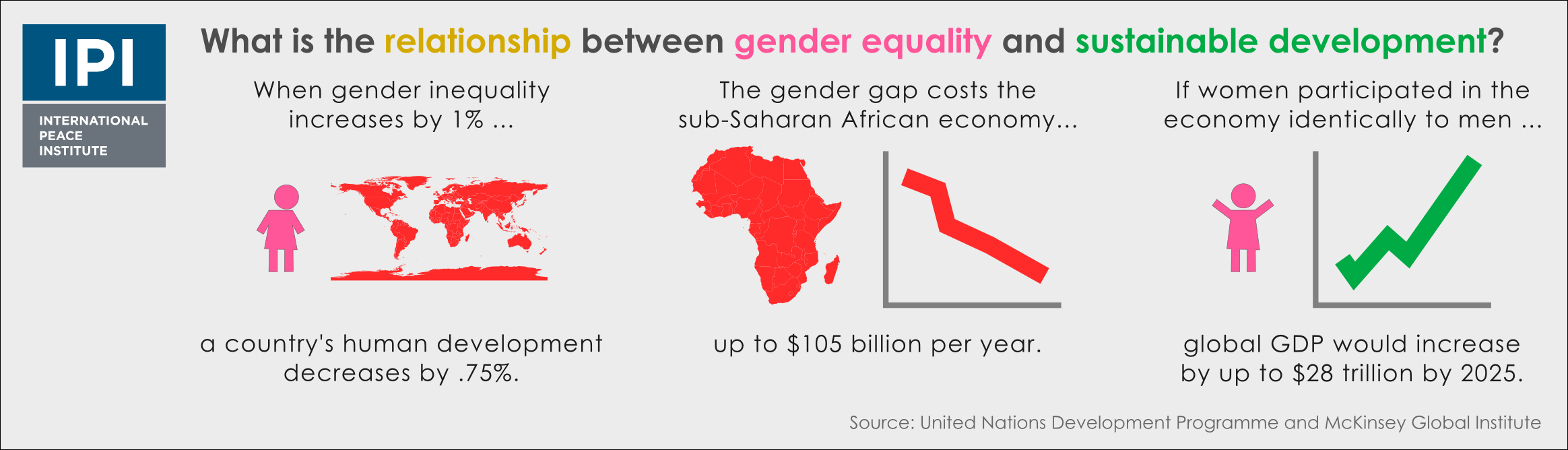

While human development is on the rise across Africa, with some of the poorest countries making the greatest strides over the past 20 years, the gender gap remains a major barrier to full economic growth. The UNDP report compiles and presents strong evidence on this link: When a country’s gender inequality increases by 1%, its human development decreases by 0.75%. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, the gender gap costs the economy an average of $95 billion and up to $105 billion per year. Gender equality and women’s empowerment are not only human rights, they are smart economic policy.

In an interview with the Global Observatory, Ayodele Odusola, UNDP’s Chief Economist for Africa, said that many heads of state in Africa have reacted strongly to the report. They’ve expressed surprise at both the gaps still to be overcome and the potential positive economic impact that gender equality can bring.

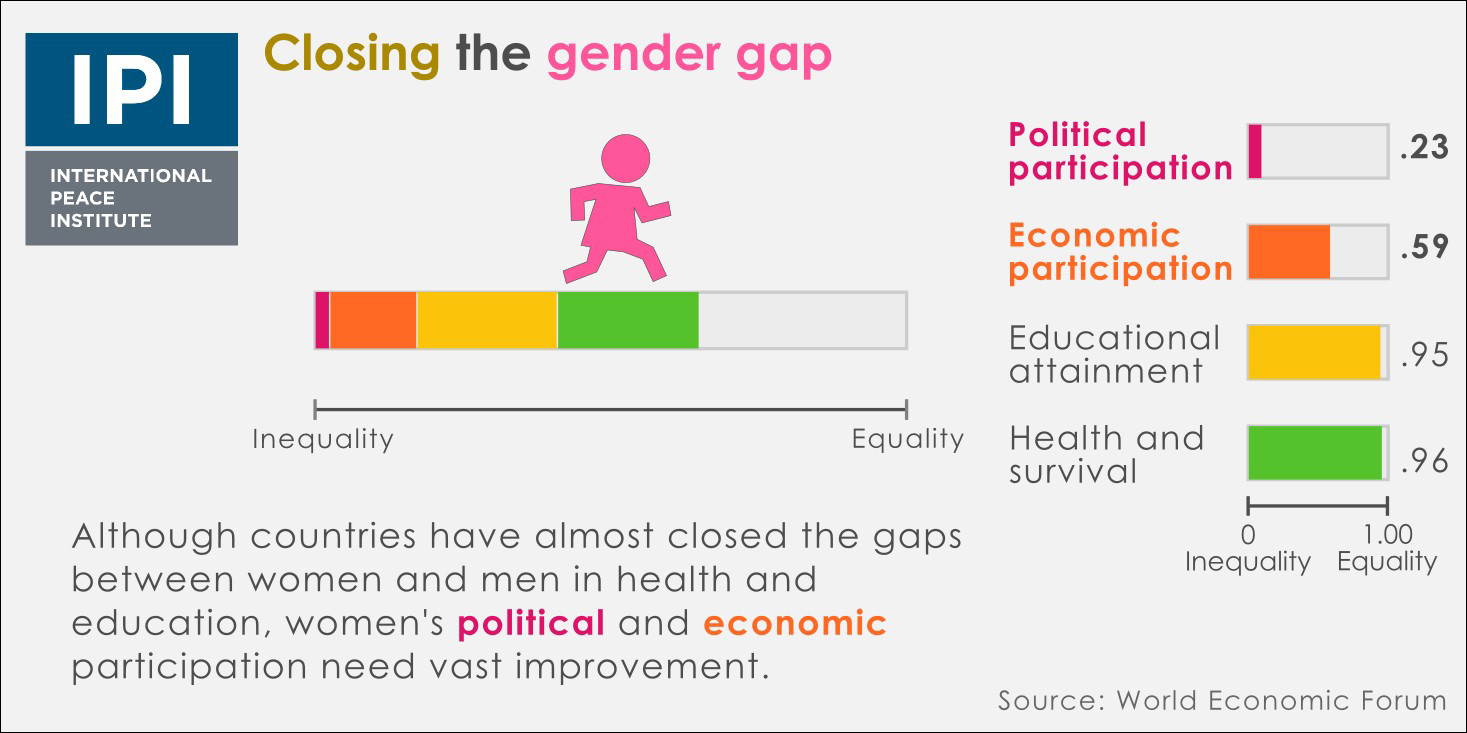

The report also makes an important link between gender, development, and peace. Studies show that increasing women’s participation and representation in leadership and decision-making positions leads to higher levels of peacefulness and better development outcomes for society. Closing the gender gap helps restore trust and confidence and enhances the sustainability of policies and resilience of communities. Despite this evidence, globally, political and economic participation have been the slowest areas of gender inequality to change when compared with women’s educational attainment and health advances.

Where communities are affected by fragility, gender equality becomes critical to violence prevention. “Before we started the study,” said Odusola, “we thought that involving women in conflict resolution was the focus. Later, we realized that’s just a part of it. The only way to create a sustainable and peaceful society is to prevent conflict through the involvement of women in articulating development priorities.”

The report features reflections from Leymah Gbowee, Liberian peace activist and Nobel laureate, and highlights the participation (or often the exclusion) of women in peace processes across Africa. It emphasizes an often overlooked effect of women’s economic empowerment: their increased ability to influence peace processes and ultimately participate in political life. As UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon reported in 2010, women’s economic participation not only contributes to durable peace, “greater participation in the workforce often provides women with the resources, status and networks needed to enter the political sphere, whether by contesting elections or engaging in civic activism.”

Most African countries have set up ministries and institutions focused exclusively on women or women and families, following the conventional practice in other regions. To advance gender equality, the UNDP report argues, African states need to integrate it as a shared responsibility across institutions and ministries. But national mainstreaming is not enough. “You cannot accelerate gender equality or women’s empowerment without deconstructing the harmful social norms in the society. It’s not possible,” Odusola said.

Social norms and cultural barriers are at the center of the report’s analysis, revealing great differences across the African continent. Where traditional and community leaders have been engaged as champions, progress has been achieved. In Niger and Burkina Faso, for instance, the Ecole des maris (“school for husbands”) project gathers influential men at the community-level to discuss family planning, gender-based violence, and girls’ education. This peer group for men advocates for more gender equality and, according to Odusola, “has made more progress in two to three years than the previous two to three decades of programs.”

Integrating a gender lens, as Odusola explained, is not only about women. It reveals much more detail about inclusion and exclusion in society. For example, in Lesotho and Swaziland, UNDP found more girls than boys enrolled in school. “At the age of 12, many boys migrate to South Africa to work in the mines. Boys drop out of secondary school in great numbers and we see reverse parity,” said Odusola.

Through regional consultations for the report, UNDP researchers discussed gender and inclusion in communities affected by extremism in sub-Saharan Africa. In these often marginalized communities, “Poverty is endemic, inequality is endemic, and one way they thought to correct that is to be a government for themselves. So they create a parallel government, and conflict starts,” said Odusola. To prevent violence, communities called for more inclusive decision-making processes that include women, youth, and other excluded groups, to build a sense of ownership and responsibility in their society.

This call for more participatory policymaking is echoed in recent international agendas, including the UN’s 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals. A gender lens can provide an organizing principle for addressing and implementing not only the sole goal on gender, but all of the global goals. As the Africa Human Development Report proposes, “… gender equality should be the lens for operationalizing a ‘leave no one behind’ agenda.” From stable societies to communities affected by violence, the potential of gender equality is clear; as this report concludes, “If development is not engendered, it is endangered.”