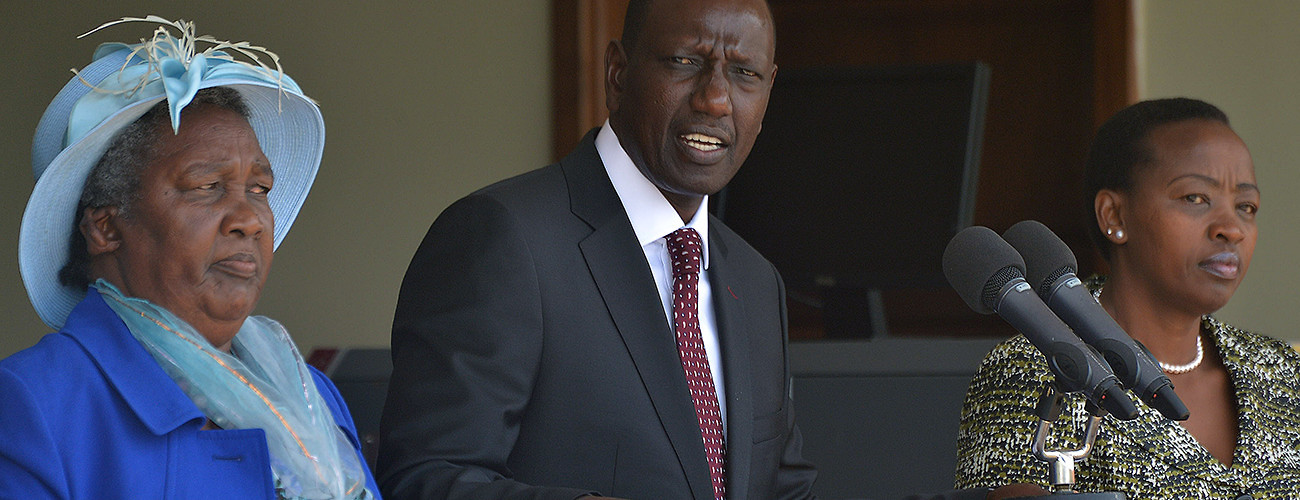

Kenyan Deputy President William Ruto addresses the media after the International Criminal Court ended its case against him. Nairobi, Kenya, April 8, 2016. (Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images)

For the past five years, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has tried and failed to prosecute six people considered responsible for inciting Kenya’s post-election violence of 2007-08. Faced with witness tampering and political interference, judges in The Hague last week terminated the last remaining case, which was against current Kenyan Deputy President William Ruto and broadcaster Joshua Arap Sang. This failure reinforces some of the ongoing challenges for the ICC mandate.

After more than two years, and 157 trials days, the ICC ended the case against the two men without delivering a verdict. Both were accused of being part of a network that organized and financed an explosion of chaos and violence after Kenya’s 2007 elections. They were charged with three counts of crimes against humanity, among them murder and persecution. The chamber concluded that the prosecution did not present sufficient evidence to convict the two men but also found an acquittal “was not the right outcome.”

The decision brings to an end the international community’s efforts to prosecute crimes committed during the 2007-08 unrest. More than 1,300 people were killed following disputed presidential polls, but Kenya’s national authorities failed to take action. In 2010, the ICC stepped in and opened an investigation, which led to the indictment of six Kenyans also including Uhuru Kenyatta, who later became president.

However, all of the subsequent proceedings were terminated early and the court did not reach a verdict in any. The ICC Office of the Prosecutor complained repeatedly about a lack of co-operation by the Kenyan authorities, primarily their unwillingness to provide evidence such as cellphone data. In the case against Ruto and Sang, 16 of the 42 prosecution witnesses stopped co-operating with the court and refused to testify because of threats, intimidation, and fear of reprisals. Several other witnesses admitted during their testimonies to have told lies to the prosecutors in return for money.

Initially hailed as one of the ICC’s most important endeavors, the prosecution of high-profile Kenyan politicians became one of the court’s most devastating setbacks. The difficulties encountered are not unique to the East African country. Rather, they highlight some major challenges for the ICC in a range of circumstances.

First, the ICC continues to suffer a lack of international support. Since it does not have executive powers or its own police force, it has to rely on governments for both practical and diplomatic support. In Kenya, external hostility was a major challenge. Several African governments turned against the court and its proceedings. The remainder of the international community, particularly the ICC’s other member states, remained mostly silent. The United Kingdom, for example, invited Kenyatta to make an official state visit in 2013, despite his indictment. Meanwhile, the President of the United States (not an ICC member state), Barack Obama, has sent mixed signals: On his first African tour, in 2013, he avoid meeting with Kenyatta and Ruto. On his return to the continent last year, Obama met with both men. Botswana was one of the few 124 ICC state parties that publicly defended the court’s actions in Kenya against the attacks from other African governments, and lobbied for the investigation to continue.

This general lack of support has hindered the court’s effectiveness on several previous occasions. In 2014, for example, the Office of the Prosecutor was forced to shelve its investigations into the conflict and alleged genocide in Darfur, Sudan, due to a lack of co-operation. The United Nations Security Council, which referred the Darfur situation to the court, refused to pay for the investigations or provide diplomatic support. This was considered critical to the failure to arrest suspects including Sudan President Omar al-Bashir.

The Security Council has the potential to increase co-operation with ICC proceedings in the future. In theory, it has the power to impose sanctions to increase the co-operation of governments in cases it refers to the court. As a less forceful alternative, it could develop an arrest strategy and clarify what action states need to take.

A second major lesson relates to the work of the Office of the Prosecutor. Outside observers and lawyers for the defense have argued that the prosecutors in the Kenya cases overstepped their mandate and overestimated their abilities. They have relied too heavily on dubious witnesses and hearsay as evidence. When these witnesses withdrew, the prosecutors were left empty-handed.

This highlights the importance of building more stable cases in The Hague. According to a recent Office of the Prosecutor report, prosecutors need 50 to 60 witnesses for an average case. The Kenya cases have shown the significance of having many more backup witnesses on top of this figure. The report estimates prosecutors need roughly 170 witnesses per case to be ready for trial—a ratio of more than two back-up witnesses for every person to take the stand.

In addition, prosecutors could rely on sources other than witnesses and evidence provided by governments. Forensics and evidence collected online, for example, could complement and support witness testimonies and makes prosecutors more independent. Without reform, the difficulty of obtaining co-operation from states could be a major challenge for the ICC’s investigation into the 2008 Russian-Georgian war, among other cases.

In order for the ICC to enforce its mandate, it is essential for it to receive support from a variety of actors, including national governments and the Security Council. While the ICC can do little to enforce co-operation, it can develop creative ways to become more effectively independent. The Kenya case should also trigger a re-thinking of the way the Office of the Prosecutor builds its cases.

Benjamin Duerr is an international criminal law analyst based in The Hague. Follow @benjaminduerr