Girls attend class in a UNICEF Child and Family Protection Zone for Syrian refugees. Amman, Jordan, February 17, 2014. (Thomas Koehler/Phototek/Getty Images)

Taha’s dream at the moment is to become a hair stylist. “She has talent for it,” her mother says. Taha* is 16 years old, from Homs, Syria, but had to flee with her family when fighting from the civil war threatened their lives; both her father and brother were injured by the war and needed medical treatment. Unable to cross the border to Jordan because of the conflict, she traveled with her parents and sister by car to Lebanon, and from there flew to Jordan to take refuge with relatives.

In fear of being arrested by the Syrian Army, her brothers had to take a more difficult route. Although they had passports, they could not travel legally, and had to cross illegally into Turkey, take a plane to Istanbul from the border, and then fly to Amman. Their escape tells of a family with resources, yet refugee life is still full of challenges.

For Taha, it seems as though vocational training would be a good path. NGOs and community centers provide short-term courses and skills training programs, and beauty and hairstyling are among the most frequently offered. However, this path is not easily accessible. According to international education experts in Jordan, the Jordanian government is not interested in any formal integration of Syrian refugees in the Jordanian labor market, and they point to the high domestic unemployment rate to justify this decision.

Worse, international organizations say the government does not want Syrian refugees to receive training, as they would compete with Jordanians for jobs. Only in the Zaatari refugee camp are the organizations able to overcome this barrier by offering skills development along with general life-skill courses. However, these programs are not certified, and so graduates would not receive any documented proof of completion. Anyway, the camp is too far away for Taha, and outside the camps, organizations are not able to provide the courses she is looking for.

Taha only reached 6th grade in Syria before it became too dangerous for her to continue; she was 12 years old. She describes herself as an average student—not top of the class, but she could follow along without difficulty.

When her family found an apartment to rent in Amman, both Taha and her younger sister signed up to continue their education. “At that time I had a gap in my schooling of a little more than one year,” said Taha. “I did a placement test and started in the second semester of 7th grade and continued into 8th and 9th grade. I went to school here for about two years, but I stopped. I had trouble when I started school here because the subjects were different and difficult for me. Sometimes I could not understand what they were talking about in class.”

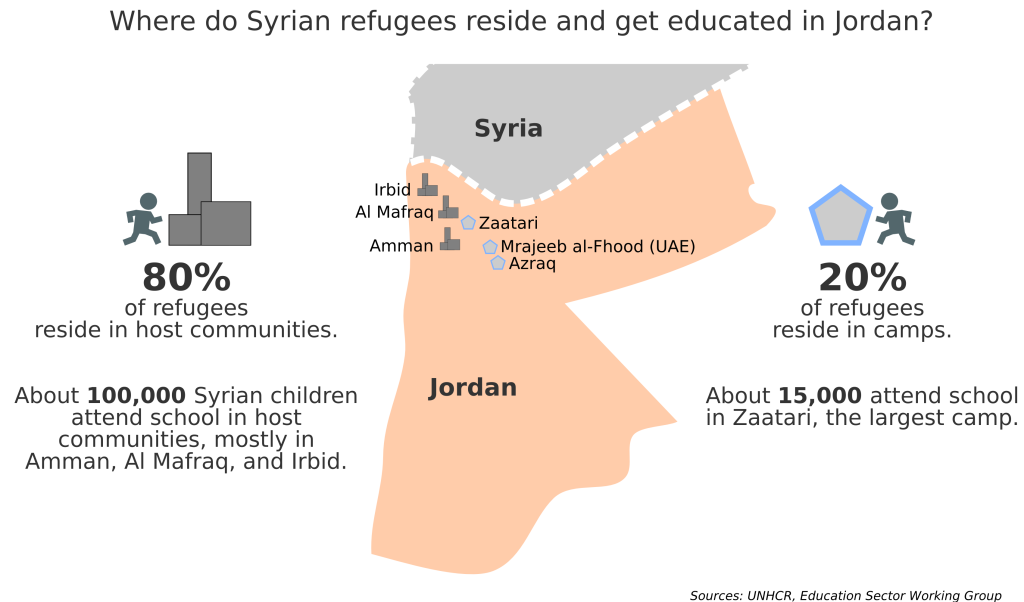

As a result, Taha is a school dropout, one of 65,000 Syrian refugees of school-going age in Jordan host communities not attending formal school. She used to be among the lucky 60% that had been generously integrated into the overburdened Jordanian public school system. Recognizing the importance of education for a county’s economic and social development, it has not only been declared a human right, but has also frequently become part of an emergency response to conflict and disaster because of its many benefits. In the short term, school offers daily routines that provide stability for disrupted lives, which enhances individuals’ capacities to deal with trauma and handle challenges as a refugee. In the long term, education is fundamental to poverty reduction, development, and economic growth, which is important for the stability in Jordan, as well as the post-conflict reconstruction in Syria.

But in Jordan there are simply not enough schools and not enough qualified teachers to integrate all the Syrian students. Further, donors often perceive young children as more vulnerable than adolescents and youths like Taha and thus focus on primary education. An international education expert in Jordan said it was easier to raise money for young children than older ones. Indeed, on a recent field trip to Jordan I found most young Syrian children I met were in school, while the older ones I encountered were struggling. One obvious reason is that school becomes more demanding, which makes it more difficult to catch up with peers, particularly when no extra assistance is offered, as was the case with Taha. Catch-up classes become even more complicated at higher levels, since post-9th grade students take alternative tracks according to individual choices.

In Jordan, it’s not only Syrian children that drop out of school; many Jordanian children are also struggling, as are children across the Middle East. Recognizing this problem, in 2003 the Jordanian Ministry of Education (MOE) together with the organization Questscope, developed a program that was based on alternative teaching methods but followed a MOE-approved curriculum to help children graduate middle school. Today the program is open to Syrian students, and about 70% of the participants are Syrian refugees.

This program could be an alternative for Taha to get her middle school certificate. Although it is better suited for Taha’s needs than a formal school, she will probably not apply. At the moment, she doesn’t regret quitting the Jordanian school and refuses to go back; she will consider education only if she goes back to Syria where she can have the Syrian curriculum and where she understands what happens in class.

But going back to Syria is not an option for Taha. The civil war rages into its fifth year, with no political or military solution in sight. Some observers are asking if schools can be created in Jordan that offer the Syrian curriculum. However, host country governments have concerns that this kind of parallel education system will create a similar entrenched situation as is happening with Palestinian refugees and the UN Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA), which provides them with relief and services. Governments also fear that building structures and institutions for the refugees will encourage them to stay rather than facilitate their return. In addition, Jordan has its own challenge, with thousands of their own young people in need of a path back to formal education. The Jordanian government thus has little appetite for providing separate services to the Syrians, and some see Syrians as already having access to aid that is not available for Jordanians with similar needs.

Taha is currently looking for a job. She has approached some hairdressing salons and asked for work, but has had no success, not even an offer to sweep the hair off the floor. With modest expectations, she hopes to be paid 5 Jordanian dinar (7 USD) a day if she is lucky. “I cannot even find this kind of work if I do not take a hairdressing course. So I need to find the course first,” she said. And even with that training, there are no guarantees for Taha, as Syrian refugees are denied access to work in Jordan. This is not because of a law barring Syrians from getting work permits, but rather because their work permits are not approved. In addition, the application and approval process for work permits is expensive and mostly out of reach for the Syrian refugees.

But many refugees find work anyway—they have to make ends meet. The level of food aid is considered insufficient, and refugees in host communities also have to pay rent. Working illegally in the informal sector exposes refugees to exploitation and abuse. Some refugees told me they were never paid for work they had done; others said the unions had started to look for and root out illegal workers. A young man told me that when he was caught, he had to sign a vow never to work without a permit in Jordan again, and that if he was caught a second time, he would be deported. These raids are not only creating fear among Syrian workers, but are also deterring some from working altogether. Additionally there are implications here for protection of vulnerable refugees according to international law.

For Taha, we have to ask: what future can we offer her? She is not a girl who sits home in despair. Through a friend, she has found a course in English and computer skills through Caritas, an NGO. It keeps her busy five afternoons a week for the time being. Taha is still among the lucky ones, but if Jordan aims to be a modern society, it is not enough. In a modern world, young people will need more than a six-month skills-training course to be useful in a competitive labor market. That is our challenge in ensuring Taha and her peers can build a decent life.

Mona Christophersen is a researcher at Fafo and a Senior Adviser at the International Peace Institute.

*The author met Taha and her family during a field visit to Jordan in May 2015. Taha is not her real name. For further reading on education for Syrian refugees in Jordan, read the author’s full report, published by the International Peace Institute.