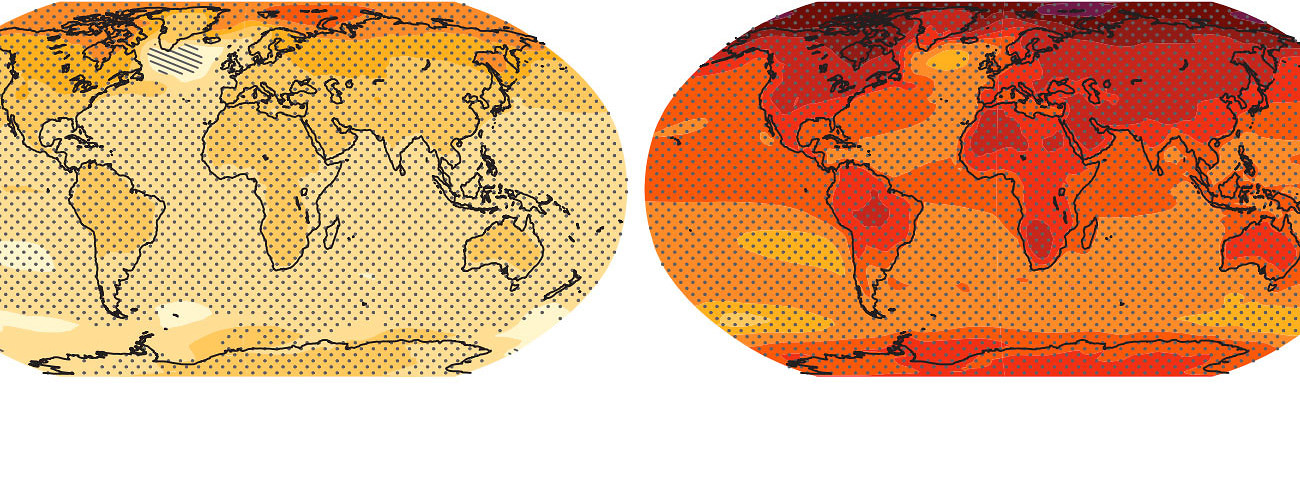

Changes in average surface temperature 1986-2005 (L), and predicted for 2081-2100 (R) using computer modeling. (Source: IPCC 2013 Summary for Policymakers, Working Group I)

“You can’t call in an airstrike on a warming climate,” said Daryl Copeland, former Canadian diplomat and author of Guerilla Diplomacy, in outlining what he sees as the major challenges facing the multilateral system today.

“You can’t garrison against the encroachment of pandemic disease, and you can’t send out an expeditionary force to occupy the alternatives to a carbon economy.”

Copeland said science- and technology-related issues such as these were greater threats than religious extremism and political violence for the United Nations and other multilateral organizations.

Speaking with Global Observatory Editor Marie O’Reilly, he said today’s diplomats aren’t equipped with the skillsets to deal with these types of challenges and argued for the adoption of “science diplomacy.” This would see diplomats working together to advance scientific goals, scientists overcoming strained relations between countries to advance their work, and scientific evidence informing key decisions made by policymakers and politicians.

The conversation was part of a series of interviews done on the sidelines of the inaugural retreat of the Independent Commission on Multilateralism (ICM) on February 19-20.

Listen to interview (or download mp3):

In your view, what are the biggest threats and challenges right now that the multilateral system is facing?

Contrary to mainstream opinion, my conclusion is that the key threats and challenges facing the multilateral system have little to do with religious extremism or political violence. Rather, it’s a host of issues that have in common a very significant element of science and technology which drive them. So whether it’s climate change; diminishing biodiversity; species extinction; weapons of mass destruction; environmental collapse; management of the global commons—the forest, the seas, outer space, the internet; or any of the whole array of matters from biotechnology to new materials.

These are all issues that have no military solution. You can’t call in an airstrike on a warming climate. You can’t garrison against the encroachment of pandemic disease, and you can’t send out an expeditionary force to occupy the alternatives to a carbon economy.

So what does the multilateral system have to deal with? It has to deal with a group of issues that I would summarize as being cross-cutting, unresolved, transnational, and science-based.

Are diplomats equipped to deal with these kinds of challenges today?

Were it only so. You could ask yourself how many diplomats are scientists? How many scientists are diplomats? How often do scientists and diplomats gather? Do we have that capacity in our institutions—that absorptive capacity, that problem-solving ability? I don’t think so, and science diplomacy is the answer to that riddle. I think it’s probably the single most important new direction in diplomacy and international relations to date in the 21st century.

What is science diplomacy?

Science diplomacy involves three sub-sections. Diplomacy for science; so that’s when a bunch of diplomats get together to try and advance scientific goals. Science for diplomacy; that works when political relations are strained, blocked, or non-existent. So, for example, during the Cold War there was a lot of science for diplomacy—cultural exchanges, people, scientists going down spending time together, Americans and Russians on Antarctic ice stations, what have you. When formal diplomatic communications aren’t working and the scientists keep talking. So that’s science for diplomacy. And finally, science in diplomacy, and that’s high-level scientific advice going to decision makers and policymakers, and filling them in on what they need to know to make the right kind of decisions about these wicked science-based issues.

How does this relate to your idea about guerrilla diplomacy?

If you’re going to do science diplomacy effectively, I think you’re going to have the qualities of the guerrilla diplomat. So you’re going to be self-sufficient, self-reliant; you’re going to have cross-cultural communications abilities; you’re going to have problem-solving skills; you’re going to have survival skills. These are an array of capabilities that are better developed doing grassroots NGO work or world travel than spending years and years in the finest Ivy League institutions.

I’m not saying that formal knowledge isn’t important because it remains terribly important, but there’s another dimension that we have to find a way to embed in our diplomats in the 21st century so that they can improve their performance and improve effectiveness. And doing this science diplomacy, particularly, you need a supple skillset—that’s the soft side of it—backed by the knowledge of biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, what have you, such that you can bring the two together in a way that advances science for diplomacy, diplomacy for science, and that high-level advice, science in diplomacy.

What role do you see for the United Nations in all of this?

The United Nations is the central place where all of this stuff has got to come together because if we don’t perfect the multilateral system, which is to say finding a collective way forward, we’re going to find enormous inefficiencies in the way that we’re broaching these very complex issues.

I think that there’s a way to characterize, really, the sorts of threats and challenges—to bring the conversation back to where it started—in the 21st century. We’ve got this environment, this operating environment, it’s characterized by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. That makes for very, very difficult navigation. So the old pinstripe-and-pearls set that we think of in terms of traditional diplomats, either multilateral in the UN system or bilateral working out of foreign ministries, they may be necessary, but they are not going to be sufficient if we’re going to successfully address this host of… let’s call it the globalization suite of threats and challenges, with the big scientific and technological dimension.

For that, we need the science diplomacy, and to do the science diplomacy right we need diplomats with a whole array of skills and abilities, which at the moment they are without. So, we’ve got to get to work.