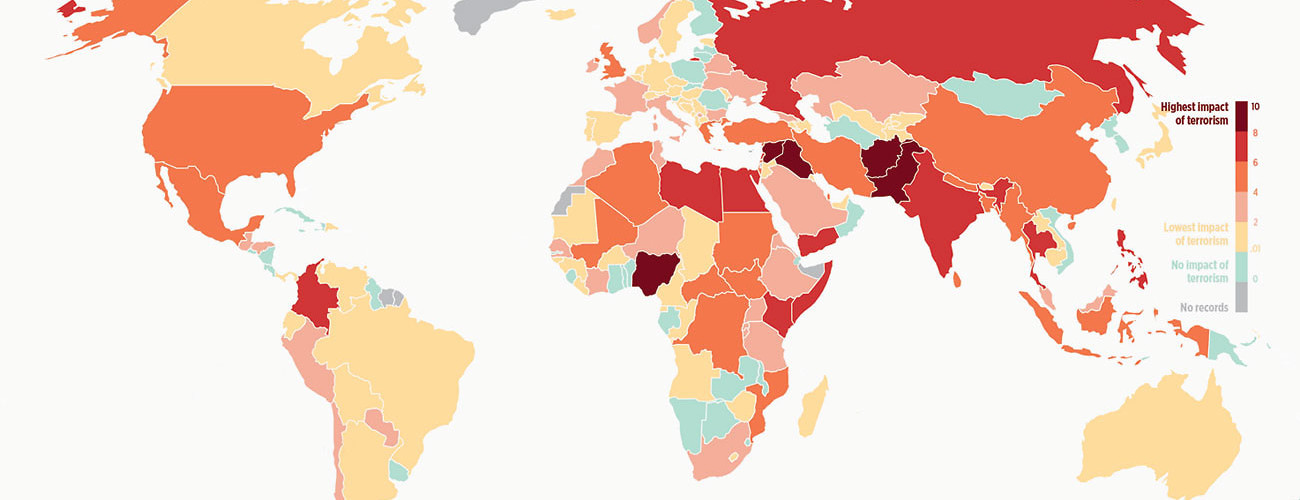

A snapshot of the 2014 Global Terrorism Index. (Source: Institute for Economics and Peace)

Creating an environment of fear is at the heart of terrorism. We see this in the ultra-violent propaganda of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS), which underscores how important mythmaking is for a terrorist group to succeed. And as the gulf between real and perceived threats widens, how can the public and policymakers begin to better understand risks? Data has an important role to play in contextualizing the true risks and threats, tempering sensationalist public discourse, and informing policy responses.

One of the most striking trends in global affairs in the last four years has been the rise in the real and perceived threat of terrorism to international peace and security. Amid a backdrop of growing geopolitical tensions, civil war in Syria and Libya, and record numbers of refugees and displaced people, the recent increase in terrorist activity has been a major driver in the decline in world peace.

For many, this has been a surprising turn of events. Rewind to mid-2011, and it is perhaps easy to see why. Ten years after September 11, Osama Bin Laden had been killed, and many policymakers were anticipating the complete defeat of al-Qaeda, along with a greatly diminished threat of international jihadism. The number of deaths from terrorism was falling from the height of sectarian violence in Iraq in 2007, and there hadn’t been a major group-based terrorist attack in the West since the London bombings in 2005. Gallup polling on the threat of terrorism in the US showed that the American public was at its least worried point for several years.

Today, the situation has shifted dramatically. The recently released Global Terrorism Index report (GTI) from the Institute for Economics and Peace shows that between 2012 and 2013, the number of people killed in terrorist incidents saw the largest increase in history, to 18,000 lives lost, which is a 61 percent increase from one year to the next.

The large increase in terrorist activity in 2013 underscores the fact that ISIS’ murderous sweep across Syria and Iraq in 2014 (which is not yet recorded in the Index) should not have been wholly unforeseeable. A basic scan of the numbers shows that terrorist deaths in Iraq rose 162 percent between 2012 and 2013. Syria meanwhile, embroiled in its civil war since 2011, moved from zero recorded terrorist events in 2010 to the country with the 5th highest level of terrorist impact in the world in 2013. These numbers ring clear alarm bells.

The data clearly shows that the real threat, impact, and risk of terrorism in Iraq and Syria was increasing, let alone in Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, rounding out the five countries that account for 82 percent of total global terrorist activity.

All this suggests the subsequent violence we’ve seen in Syria and Iraq in 2014 should have not been a surprise. But as is increasingly clear, the emergence of the ISIS threat—and also of other major groups like Boko Haram—did indeed take governments and policymakers by surprise, and there was no clear strategy and response.

While there is significant and growing risk in the countries with the most terrorist activity, terrorism has remained relatively lower in the rich countries of the world where most conventional counterterrorism resources are directed.

Here, the data shows the occurrence of terrorist activity in the rich nations of the world is more the exception rather than the rule. Even counting some of the most devastating terrorist attacks in the last 14 years that occurred in OECD nations, such as September 11, 2001, the Beslan school siege, the Madrid bombings, the London 7/7 attacks, and the 2011 Norway Utoya attack, only five percent of total global terrorist deaths from 2000-2013 occurred in OECD nations.

While the current impact and risk of terrorism is sobering, for most countries there are much greater risks. To put this in perspective, there are 40 deaths from homicide for every one terrorist death.

The recent pattern of events and “what the data says” about terrorism suggest at least two key things. First, the real risks of terrorism are not well understood, and large gaps exist between what the real and perceived risks are. On the one hand, real risks of terrorism where it mostly occurs—in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Nigeria, and Pakistan—have been underappreciated, where in the OECD countries, the perceived risks of terrorism significantly outweigh the real risks.

Second, the data suggests that current global approaches to terrorism are not working. Analysis in the GTI report shows, perhaps unsurprisingly, that countries with authoritarian regimes that impose high levels of political terror in contexts of low intergroup cohesion and high levels of group grievances statistically tend to have higher levels of terrorism. This is intuitive—the same factors that create broader societal conflict also drive terrorist activity.

However, when we compare the paucity of spending on peacebuilding aimed at redressing identified “root causes” compared to conventional domestic counterterrorism efforts, there is a clear mismatch. The need for longer-term and new approaches to counterterrorism based on addressing political, ethnic, and religious exclusion, inequity, and countering violent extremism is acknowledged but will clearly take many years to set in motion.

In the meantime, generating evidence and data and communicating “what the data says” remains a practical and immediate tool to help contextualize and address terrorist violence.