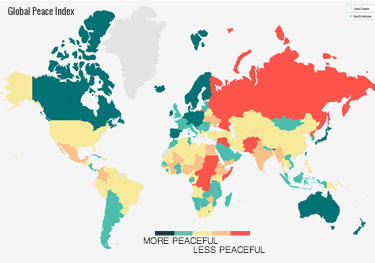

A modified screen grab of the 2014 Global Peace Index. For the dynamic version that includes previous years, go here.

The 2014 Global Peace Index released its findings last month, concluding that peacefulness worldwide has dropped for the seventh straight year (the index itself started in 2007). Daniel Hyslop, research manager for the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP), which produces the index, talked to the Global Observatory last week about what that means. The interview was conducted by Ramy Srour, Assistant Web Editor at the International Peace Institute.

How does the IEP measure “peacefulness,” and what would you say are some of the challenges in capturing this concept?

The definition of peace in the Global Peace Index is negative peace. And that is the absence of violence, or the absence of the fear of violence. So we’re measuring direct violence. That’s in contrast to something like positive peace, which is really about the institutions, attitudes, instructions that underpin an environment that is not violent.

One of the challenges to measuring violence is the availability of data. We’re covering 162 countries. You can’t always get data for 162 countries on their levels of violence. That’s why we use both qualitative and quantitative measures.

The index has three cross-cutting domains: measures of societal safety and security—so all the things that you think about when you think of violence like levels of homicide, levels of violent crime, number of people in jail, number of police officers that you require to keep the environment peaceful. Levels of militarization is another cross-cutting domain; essentially, a country ‘s ability to project peace externally. And that’s looking at the heavy weapons capability of the country, the number of armed service personnel.

The third domain is if there’s ongoing conflict, ongoing internal and external conflict, which is really looking at whether or not a country is engaged in armed conflict, whether or not there are non-state actors within the country that may disagree with the civilian population or with the government. That counts as well as a form of violence.

Can you tell us a little about the data-gathering problem that you mentioned? What are some of the challenges you found?

A really good example is homicide data. If you look at sub-Saharan Africa, probably only one in five states actually reports a homicide right to the UNODC [UN Office on Drugs and Crime]—which is the main UN authority that aggregates these data—a lot of those data sources are quite unreliable. So even on something really fundamental like homicide, there are large data gaps that you need to tackle with qualitative and expert assessments.

Is that where the research team then comes in?

For the Global Peace Index, we worked with about a hundred country-analysts from the Economist Intelligence Unit, who basically helped with those qualitative assessments. Their assessments are then peer-reviewed by our expert panel, who provide a level of independence for the index.

The index shows a seven-year decline in peacefulness starting in 2008, a trend which you state “overturns a 60-year trend of increasing global peacefulness.” Why 2008? Was there a turning point? And what has contributed to this steady decline in peacefulness?

The index started in 2007, and what we’ve seen since then is a gradual fall in the levels of peacefulness. This fall in peace is mainly due to terrorist activity; the recorded level of homicide; and a number of internal and external conflicts fought.

Was there any kind of turning point in 2008? Well, for some of the European states, the financial crisis had an impact on their levels of peacefulness, as there was an increase in the levels of violent demonstrations. On the converse side, there was an improvement on the levels of militarization, as a lot of European states cut back on their military spending. So the crisis had a mixed effect, but overall, since 2008, when you look at the levels of terrorism, homicide, the number of internal and external conflicts fought, and the number of refugees and displaced people, it’s a picture of a less peaceful world.

Yet, there are all sorts of mixed trends. It’s very difficult to say that there was one event. But certainly, there are two very big events you can talk about that have happened in the last seven years that have affected global peace: the financial crisis in Europe—it affected peacefulness in Europe—and the Arab Spring, which has affected a lot of Middle East and North African states. But quite separate to that, levels of terrorism, specifically in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, have really accounted for the decrease in peace.

When we think of peace and conflict, we often think of active engagement. But the index also looks at the mix of conventional and non-conventional indicators of violence within a state, such as demonstrations and incarcerations. Why is that the case? Why can we do this with violence and conflict, conflating internal and external dimensions? And what does this tell us about the meaning of peacefulness and a state’s relationship with the international system more broadly?

That’s a good question. You have to come back to the definition of the Global Peace Index, which is negative peace, i.e., the absence of violence and the absence of the fear of violence. So, the reason why you need 22 indicators is that violence, or negative peace, is a multi-dimensional concept. You can’t measure it just through one indicator.

So the idea is that high levels of incarceration are not reflective of a truly peaceful society. In some sense, the starting point for the index is a utopian one: a perfect society where you wouldn’t require police, you wouldn’t require jails, and you wouldn’t require a military, because everyone would get along nonviolently. That’s very much the reason why you need to include those other indicators. They are reflective of the fear of violence. And that’s something that we’re trying to get at by measuring those things.

In terms of the link to the international system, we’re trying to look at the relations with neighboring states, such as diplomatic relationships. We look at the number of heavy weapons a country has—so its ability to project violence; we also look at nuclear weapons capabilities. We look at whether or not there is cooperation between states on an international trade level. The idea behind that is that states that do poorly in those areas will tend to be more violent internally. There is actually a correlation between your levels of militarization and your levels of societal safety and security; the two things are actually quite closely linked. And in order to measure violence comprehensively, you need to count them both.

What would you say is the relationship between the index and the concept of state fragility?

Essentially, if you look at the index and you do a correlation of the prominent measures of fragility, the Global Peace Index and other indexes would be upside down. Countries at the bottom of our index are the very violent, and those are the countries that would also tend to be classified as fragile.

Now, what we did in this year’s report was to develop a risk tool that actually tries to look forward at fragility. If you look at the prominent measures of fragility like the World Banks’ API tool or the Fragile States Index, these tend to identify fragility now—what countries are actually violent and unstable, and whether there is a lack of legitimacy—and lack predictive power. What we are more interested in is looking forward, trying to look at the next two to five years. What are the countries that could become fragile?

Would you say that, for the ten countries the risk tool singles out as being at risk of violence [Argentina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Chad, Georgia, Haiti, Liberia, Nepal, Qatar, and Zambia] the tool is predicting instances of violence? Can the tool function as an early warning system that could be used by the UN community or other international organizations to take a closer look at these countries?

Our risk tool is very much trying to be a predictive tool of what other countries are going to experience—that is, small-to-medium deterioration in their levels of peace in the next two years. We’re looking at the institutions and structures that underpin a society and looking at its history of conflict to determine that.

But what you can’t do is predict shocks. You obviously can’t predict an earthquake, or you can’t predict a major natural disaster event. What you can predict, however, is the country’s history of violence, its institutions, its attitudes and structures, and how those things relate to each other over time, and how the country might respond if there was a shock.

So that’s what we’re saying: That those countries lack resilience and are vulnerable to a shock, if that shock does happen. That’s very much what that list is trying to do, and that’s relevant for early warning, because you want to be able to understand how resilient those places are going to be if there’s a shock.

What we’ve observed is that the countries that we’ve identified at risk have tended to fall in their levels of peace. Shocks tend to be more prominent in these places, and when they happen, they tend to result in a fall in peace and an increase in violence. So, you’ve got to be very careful when you talk about prediction, because it’s a tricky area, but certainly, what we’re trying to do is predict the resilience of a country if there is a shock, and what we’ve seen is that it’s been quite accurate in terms of doing that.

There are some experts that say violence has declined worldwide, such as Steven Pinker in his 2012 book Better Angels of Our Nature. But there are also others who say, as the index shows, that violence has increased. Why would you say some view it one way, and others the other?

Steven Pinker’s analysis is actually looking at a much longer time period. He’s looking at the last 10,000 years, the history of humanity. That’s the first thing I’ll say. In any case, his claims have been thoroughly investigated in the Human Security Report, which has wanted to go back and basically test a lot of the claims of the Steven Pinker book.

There are some people who disagree with Pinker’s methodology for calculating the decrease in violence in the last 50 years. One of those ways is that he takes account of population growth, so as the world’s grown so much, your per capita amount of death on a per person basis is less. With that method, WWII for instance, even though it was an enormous event and killed millions of people, if you compare it to other major conflicts, because of the size of the global population at the time, it is not as drastic. And there’s been a lot of criticism about that. However, although a lot of his claims are being reviewed in the report, his findings largely stand up.

Now, what we’re looking at is the trend in the last seven years, something that Pinker quite distinctly is not looking at. And what we’re way saying is that, based on the data that you can observe in the last seven years, the world has gotten less peaceful. There’s been more terrorism, more displaced people, more refugees, more conflicts.

So is it just a question of what indicators we’re looking at, or the time-frame we’re using, or is there something bigger happening?

No, I think it’s possible that if this trend were to continue for another ten years, it would naturally challenge a lot of what Pinker is saying. We certainly have seen an increase in the level of homicides in some parts of Latin America, and although it’s gone down a lot in Western Europe and in the US, the UNODC showed that five countries in South America in the last ten years have seen increasing levels of homicide. So the trends are not necessarily uniform, but when you look at the number of conflict deaths over the last decade, there’s been an increase, even if you take into account population growth.

So, yes, it does depend on what indicator you’re looking at, but I think there needs to be more time. Certainly, if it continued on this trajectory, it would challenge a lot of the notions of his book.