[A version of this article was first published by Noria Research] [en français]

Despite limited human capacity and financial means, civilian institutions have nevertheless emerged this year in the zones conquered by the insurrection movement in northern Syria. Reconstructing an administrative system from the bottom-up has enabled the public service system to restart, and it constitutes the basis for an alternative to the Damascus regime. The management of eastern Aleppo by the armed opposition thus constitutes both a strategic and a political challenge.

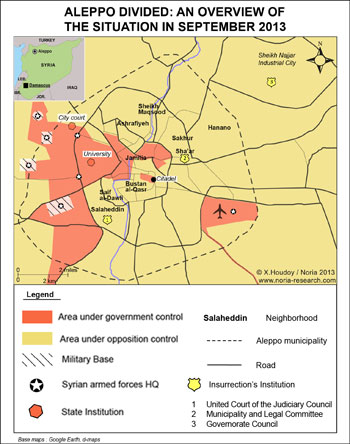

The areas controlled by the insurgency in the country’s second most significant city are home to over a million inhabitants (though the exact figure is uncertain), and their management represents a test for the sustainability of the opposition in the long run. Despite daily bombings and limited external aid ($400 000 since its creation in March, to which can be added one-off aid donations which generally add up to a few tens of thousands of dollars), Aleppo’s new municipality has managed to re-establish vital public services. City agents pick up the trash; electricity and water are available several hours a day. Shops, schools, and hospitals have reopened. The police force is progressively re-forming throughout the city, though it still numbers only a few hundreds men. In the short term, the city’s access to food seems more or less secure, and a limited return of refugees from Turkey could even be observed this summer.

Yet, this nascent administration lacks the essential resources and qualified personnel required by a city of this size. Indeed, while it is de facto providing for most of the city’s public services, the municipality is regularly confronted by competition with certain armed groups attempting to create alternative authorities, and is now under threat from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, or ad-dawla al-islâmîyya fî-l-‘irâq wa-sh-shâm), affiliated with al-Qaeda.

The Two-Fold Process of Administrative Reconstruction

The development of an autonomous administration began with the seizing of the eastern part of the city after the departure of regime forces in August 2012. The civilian activists that had participated in the organization of daily protests started then to take part in the city’s management. Already in 2011, numerous informal networks of solidarity had formed to support the peaceful protests. These groups, while lacking clear structure, tried to coordinate the demonstrations and to provide some services forbidden by the repression, such as medical care. Also, when fighting erupted in other cities, especially in Homs or Hama, some of these networks took charge of feeding and housing the displaced refugees who came to Aleppo. However, the efficiency of these first initiatives was limited by the violence of the security forces which were arresting activists and forcing them to go underground.

With the fall of eastern Aleppo, these local initiatives had to face a particularly precarious context. Part of the population fled the fighting, but a number of inhabitants stayed or returned several weeks later once their neighborhoods were liberated. The city’s access to water and electricity had been cut off because of the fighting, and the schools and hospitals–systematically targeted by the regime’s bombings–were forced to close. Winter 2012-2013 was particularly harsh for the city’s inhabitants who lacked food and heat. The absence of running water, as well as the accumulation of trash, explain the frequency of skin diseases and infections to which children are particularly vulnerable. At this time, the activist networks were the only groups available to coordinate aid and try to maintain minimal public services. In each neighborhood, a structure—sometimes two or three, under the title of neighborhood council or local council (majlis al-hay or majlis mahâli)—emerged because of the initiative of local activists.

At the same time of this bottom-up reconstruction, the Syrian National Coalition (al-itilâf al-watanî as-sûrî), regrouping different components of the Syrian opposition, was trying to rebuild a civil coordination structure at the governorate and municipalities level from the top down. In particular, a Governorate Revolutionary Transitory Council (al-majlis an-intiqâlî ath-thawrî lil-muhâfaza) was charged with organizing an administration at the governorate and city levels. Its headquarters, based in the industrial neighborhood of Sheikh Najjar, became an administrative center through which other institutions connected, such as the Military Council of Aleppo, which coordinates the different armed groups in the governorate, the new civilian police force, as well as a radio and a television channel. However, during winter 2013, the Transition Council met with strong resistance from local councils that were questioning its legitimacy, thus reflecting greater tensions at the heart of the opposition between the activists inside and outside of Syria.

In March 2013, the integration of the two processes–the bottom-up reconstruction of local institutions and the attempt to coordinate them from the top-down–led to the organization of elections in the city of Gaziantep in Turkey. Inspired by the experience of the neighboring province of Idlib, a group of people were charged by the Coalition to select hundreds of delegates in the parts of the governorate controlled by the insurrection. This electoral body was then assembled from March 1-5, 2013, and elected the Governorate Council (majlis al-muhâfaza) and the Municipal Council (majlis al-madîna). Mohammed Yaha Nana, a former public servant of the city, and Ahmed Azuz, a “first hour activist” (meaning someone who has been involved since March-April 2011), were elected, respectively, governor of the province and mayor of the city. Each one leads a team of over one hundred workers, selected both for their professional abilities and for their roles in activist groups. Since the spring of 2013, this effort to form a hierarchical and centralized administration has been pursued through the progressive holding of local elections in the 65 neighborhoods controlled by the insurrection.

The reconstruction of this administrative apparatus has resulted in creating middle-class individuals from relatively young men from residential neighborhoods on the periphery (Salaheddine, Sakhur, Hanano). Several women from the same background have also accessed types of work that they would never have been entitled to considering their social origin: hospital coordinator, district mayor, member of the Education Department. As a result of their early engagement in the opposition and their precious technical abilities (degrees, experience in administrations)–and because many of the more educated members of the population are in exile–these men and women have become the engine of the institutionalization process taking place in the territories controlled by the insurgency, with Aleppo representing the most prominent example.

As a result of their social background, the members of the Aleppo municipality are rather close to the part of the Free Syrian Army brigades that are also composed of urban middle class. The similarity of trajectories between those two groups in the Syrian revolution explains their proximity in daily sociability and the presence of city employees in combating units outside of working hours. A certain gap nevertheless exists with the insurrection brigades who hold members from the rural areas and which are accused of lacking discipline and of imposing conservative social norms.

This social gap is more obvious when it comes to Syrian activists who live outside Syria, notably in Turkey or Europe. The latter often belong to richer families, or even to the big families that dominated Aleppo’s social life, as in the other Syrian cities. Their social networks have enabled them to leave the country more easily, with means such as the ownership of a Syrian passport, a rarity that even the mayor of the rebel part of Aleppo does not possess. Also, education degrees and a good command of Western languages have enabled these Syrians already connected to the Western world to integrate into the institutions of the Syrian National Coalition and numerous Western governmental and non-governmental organizations.

These external activists often demonstrate a certain social disdain for the members of the governorate and municipal councils, accusing them of incompetence and conservatism. As a result of all this, a large gap has appeared between those on the inside, who benefit from the social change to occupy positions of authority, and those on the outside, who scarcely interact with institutions held by the activists with whom they share little from a social perspective. A clear consequence is the strong hostility between institutions from the inside and from the outside, which in turn partly explains why the aid only rarely reaches the local councils. Another consequence is the often false perception of the situation in Syria by Westerners who are in contact almost exclusively with these Syrians living abroad.

The Re-Establishment of Public Services

Over the period of a few months, March to August 2013, the incumbent city administration has reorganized the public services despite the constant bombings and the lack of qualified employees. Garbage pick-up and rubble clearing are taken care of by former regime employees in rented private trucks. The waste, after being collected and assembled in one area of each street by the inhabitants themselves, is then sent outside of the city to a former marble carriage work now used as a dump. A sanitary team also passes through each neighborhood to spray the streets with insecticide, thus preventing the malaria epidemic that was threatening the city last summer.

The municipality also intervenes at the infrastructure level. It organizes technical teams to maintain electrical and hydraulic networks. As the engineers are outside of the eastern part of the city, the municipality has not been able to repair the transformers that had been damaged by bombings. The electricity thus runs irregularly only a few hours a day. As the network is integrated into both sides of the city, the two municipal services are forced to negotiate in order to insure the provision of electricity in their respective zones.

Another example of an indivisible good is the hydraulic network. It poses the same problem, but with a different solution. Certain water towers are located on the front line, and their access is essential to insure running water in both sides of the city. However, the army, unlike the regime’s municipal services, generally refuses to negotiate with the insurgents. As a consequence, the water debit is weak and fluctuating, even though the repaired pipes and water towers of the east side have allowed access to running water a few hours a day. On the other hand, as funds are low, the municipality is not maintaining the road network, which is deteriorating because of regime air strikes.

The Aleppo municipality aims to re-establish medical and educational services. Hospitals and schools are organized in locations held secret to avoid bombings. Specialized services, notably pediatrics and dermatology, have been re-established. On the school side, the regime’s books, or photocopied versions, are used as pedagogic support and enabled the baccalaureate exam to take place during the summer.

Despite the absence of stable resources, the municipality is able to provide for these services thanks to the largely unpaid engagement of thousands of employees. Indeed, the salaries of teachers are fixed at 25 dollars a month, but are rarely paid. The aid given by the Coalition is irregular, despite the funds allocated by Western and Gulf countries. Since its creation in March, the municipality has had to regularly call upon donations from Syrians abroad. For the months of September and October, the Aleppo municipality no longer had funds to run the city’s public services.

An Administration in Search of a Monopoly

Since it is lacking funds, the municipality cannot cover the entire needs of the city. This has left a void for militarized groups to try to impose their own administration. The question of the reconstruction of a judiciary system brought this problem into stark relief. When the city was taken in September 2012, the Free Syrian Army brigades on the one hand, and the religious and juridical personnel on the other, agreed to put together a tribunal, the United Court of the Judiciary Council (al-mahkama al-muwâhada lil-majlis al-qadhâ’i). The religious and juridical personnel pass judgment according to the Unified Arab Code (al-qânûn al-‘arabî al-muwahhad), a penal and civilian body of law based on the Sharia, and established by the jurists of the Arab League in Cairo in 1996. In addition, a police force made of former police officers (who deserted) and additional volunteers has been created under the control of the Governorate Council, and the police’s mandate is to apply the council’s court decisions. However, in the absence of proper resources—and, until recently, of any external aid—the civilian police force has been incapable of imposing their mandate to armed groups and of applying the decisions of the United Court, which, in turn, lost a large part of its legitimacy.

In the face of this judiciary system, armed groups–Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, Suqur al-Sham and al-Tawhid–established their own court in the early months of 2012, the Legal Committee (haî’at ash-sharî‘a), rather than having to submit to another authority. The difference between them and the United Court is that the Legal Committee has its own police force, limited to 200 men sent by the armed groups, and sets up checkpoints in the city. Until the summer of 2013, the tribunal refused the application of a written code, as it considered that religious competence would insure a more precise application of Islamic jurisprudence. It also imposes a religious control, such as headscarves for women and the strict following of fasting during the Ramadan month. The Legal Committee also plays a part in the city’s management, creating competing services for electricity provision, education, and medical care. Finally, by taking over first the administration of Aleppo’s mosques, which had been neglected by the municipality, the Legal Committee was able to gain control of most of the city’s mosques.

The competition between both institutions has not led to armed confrontations, but the tensions are obvious. The Legal Committee is accusing the members of the civilian administration of being bad Muslims—a strong argument in a time of jihad—while the institutions attached to the Coalition consider their rivals incompetent. Last August, men from the Legal Committee even encircled the United Court for one day until they were forced to retreat by the Free Syrian Army combatants closely related to the civil institutions—even though the members from both administrations have to communicate regularly to manage the city and contend with the armed groups. An agreement between the two competing projects would not be impossible if the Legal Committee was to align its procedures with those of the United Court, and if the municipality was to Islamize its discourse.

In the meantime, the ISIL is refusing to play this institutional game, and is directly threatening the existence of the civilian administration. This group, affiliated with al-Qaeda, was formed in April 2013 from the fusion of the Islamic State of Iraq (ad-dawla al-islâmîyya fî-l-‘irâq), the Iraqi branch of the movement, and a section of Jabhat al-Nusra, notably the foreign fighters engaged in Syria. In Syria, al-Qaeda is engaging in a process of controlling territories directly. This is a relatively new strategy for the movement, the beginnings of which were visible in its Yemeni branch (when it occupied the South of the country) and Sahel branch in northern Mali. Like in most of northern Syria, the ISIL is progressively taking control of strategic places in Aleppo, and is more and more involved in the management of its populations. A part of the administrative services of the Legal Committee joined the ISIL in April–at the same time as certain fighters from Jabhat al-Nusra–under the title of Islamic Administration (idâra islâmîyya), but this phenomenon remains rather embryonic.

The skyrocketing increase in power of the ISIL these last months has profoundly transformed the political dynamics in northern Syria. The pragmatic collaboration between groups with sometimes opposed ideologies, but united against the regime, has led to a direct confrontation that could hinder the vulnerable and fragile civilian institutions. The way that, in Raqqa, Azaz, Manbij or Tall Abiad, the ISIL eliminated the members of local administrations and now rule over the cities of Al-Dana or Saluq demonstrates the risks weighing over Aleppo’s administration. Since last summer, the United States and the European Union started to provide support for Aleppo’s police force, but many more resources are necessary to the survival of the functioning civilian institutions in the rebel-held territories.

Adam Baczko is a Ph.D. candidate at École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. Gilles Dorronsoro is a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Arthur Quesnay is a Ph.D. candidate at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.