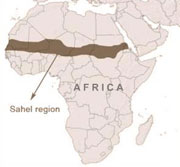

In recent weeks, the United Nations, the European Union, and a number of international humanitarian agencies warned of an impending humanitarian catastrophe in the semi-arid region of the Sahel—notably in parts of Niger, Mali, Chad, and Mauritania—due to a rapidly deteriorating food security situation. Aid agencies are urging action now to avoid another major crisis in a region regularly subject to large-scale severe malnutrition and famines. The recurrence of crises—the last notable ones in 2005 and 2009—questions the relevance of massive relief operations that address the symptoms without working on the underlying causes.

In recent weeks, the United Nations, the European Union, and a number of international humanitarian agencies warned of an impending humanitarian catastrophe in the semi-arid region of the Sahel—notably in parts of Niger, Mali, Chad, and Mauritania—due to a rapidly deteriorating food security situation. Aid agencies are urging action now to avoid another major crisis in a region regularly subject to large-scale severe malnutrition and famines. The recurrence of crises—the last notable ones in 2005 and 2009—questions the relevance of massive relief operations that address the symptoms without working on the underlying causes.

A recent report by the Sahel Working Group, a network of development and humanitarian NGOs, rightly points to the need to acknowledge the existence of a chronic food and nutrition crisis, and to take adequate measures. This requires bridging the traditional relief-development divide and engaging with the regions’ governments and communities in the longer run to address the root causes of food insecurity.

Key Conclusions

The recurrence of food and nutrition crises in the Sahel requires a change of approach by aid agencies to avoid endless and costly relapses. There is growing awareness in the aid sector that solutions to chronic food crises lay in a developmental approach that seeks to address the root causes, which implies longer-term commitments and working together with the government, local authorities, and communities. While early emergency response is needed, this response must be part of a longer-term strategy.

However, recent security developments in the region will present particular challenges in terms of access to affected populations. The increased number of well-armed insurgent, terrorist, and criminal groups in the Sahel might justify a narrower humanitarian response that prioritizes acceptance from all parts of the population and perceived independence from the government.

Analysis

The Sahel region is affected by a situation of chronic food insecurity due to adverse climate and geography conducive to recurrent droughts; widespread underdevelopment and poverty; and structural weaknesses in the areas of agriculture, trade, and social protection policies. Last year, poor rains resulted in bad harvests that contributed to an increase in food prices, further ravaging the poor communities in the region who had not fully recovered from the 2009 drought that destroyed their livelihood. The crisis is further exacerbated by other factors such as the return of several hundred thousand of migrants who fled Libya in 2011—resulting in more mouths to feed and a substantial loss of crucial remittances—and volatile security situation in Northern Nigeria that contributes to distorting regional food markets. This convergence of factors explains that the annual “hunger gap”—the period between two harvests—is expected to begin earlier, be more severe, and last longer than usual.

Risks of widespread malnutrition, which might affect up to 10 million people across the region, according to aid agencies, require immediate action to prevent a worsening situation. A number of governments in the region have reacted early by declaring states of emergency and calling for international aid, while some institutional donors have already contributed or pledged substantial amounts.

To be effective, funds not only need to be disbursed quickly to allow early preventive action, but they also have to be used differently to address some of the causes of chronic food insecurity. Aid agencies must work in the longer term to build the capacity of the region’s governments to address the food situation and be better prepared to crises, to alleviate the vulnerability of populations, and to strengthen their resilience. Critics warned against the tendency in previous crises—notably in Niger in 2005—to bypass and sideline governments, and pleaded for greater involvement of local authorities. In brief, aid agencies are compelled to adopt a more developmental approach and work together with governments of the region, local authorities, and communities, if recurrent relapses into crisis are to be avoided.

While there is growing consensus for a more inclusive approach, the response will be further complicated by recent developments on the security front that make the region more volatile than it was in previous crises. In recent years, several security threats have emerged in the Sahel: besides separatist Tuareg movements that have existed for decades in Mali and Niger, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and various criminal groups—engaged inter alia in drugs and human trafficking—have expanded their reach and activities in this vast arid region characterized by porous borders and loose state authority. A recent UN assessment mission in the Sahel found that the security situation has further deteriorated following the Libyan crisis in 2011. With the fall of Muammar Qaddafi, a number of foreign recruits of the regime returned to their country of origin while an unquantifiable number of small arms and ammunitions bled into the region, adding to the arsenal of various armed groups. Increased fighting was already reported in recent days in Mali, triggering the displacement of up to 30,000 people, while the deteriorating security situation pushed governments to increase defense spending, to the detriment of social services such as education or health.

The UN assessment mission’s report already highlighted the impact of the deteriorating security situation on humanitarian access to affected populations. It is to be expected that the influx of humanitarian agencies in the months to come, with their corteges of international staff, will unfortunately correspond with more security incidents such as kidnappings for ransom, an increasingly common practice in the region. In such circumstances, aid agencies will likely face a stark choice: engage in long-term strategies and collaborate with authorities, but risk being perceived as siding with the government, jeopardizing access to some affected population; or prioritize an independent humanitarian approach to secure acceptance from all groups and gain broader access, knowing that the impact might be limited to the symptoms of the crisis alone.

Jérémie Labbé is a Senior Policy Analyst at the International Peace Institute