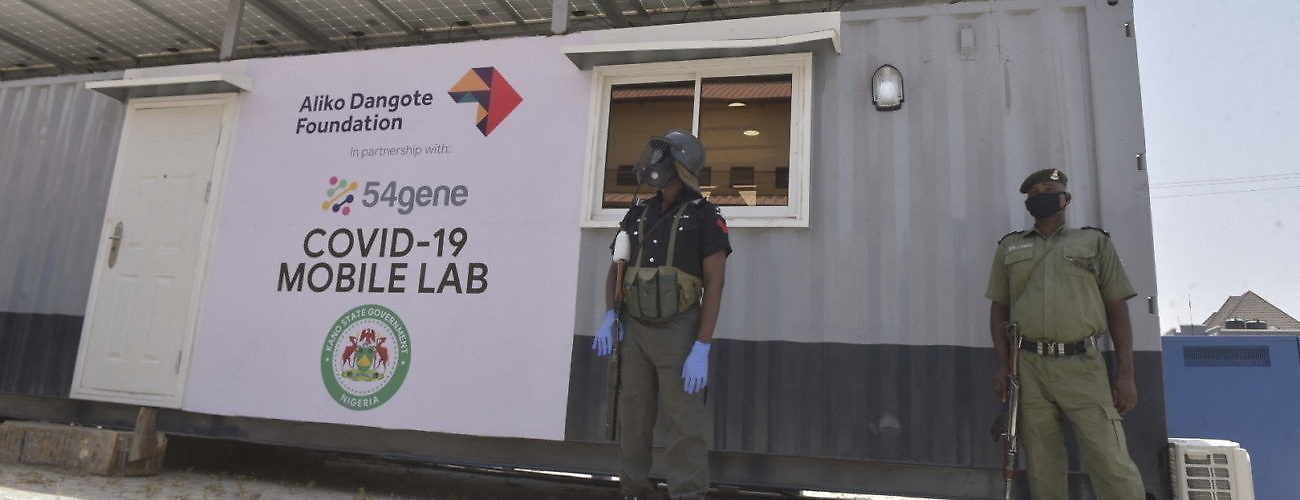

A mobile coronavirus testing laboratory center in Kano, Nigeria on May 3, 2020. (Sipa via AP Images)

Between April 29 and 30, the United States recorded around 2,700 deaths attributed to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. The US’ daily death toll—which saw the country’s coronavirus fatalities exceed the 55,000 mark—was more than the total number of deaths reported across the African continent since the novel virus was first detected in December 2019. The juxtaposition of comparative death tolls and fatality rates between countries in North America and Europe, and Africa, has raised questions as to what factors explain the discrepancy.

A closer examination makes clear that—as has been the case in many countries—low death tolls, fatalities, and the number of cases are not reliable indicators of the spread and severity of the outbreak in Africa. Hypotheses for why there are comparatively lower numbers vary. One is the continent’s hotter climate, which would perhaps impact the longevity of the coronavirus and limit its transmission. Another is the young population which can better tolerate the physiological impact of the disease.

Other explanations relate to Africa’s extensive experience in managing highly communicable diseases, and that the continent’s exposure to the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine—administered in the treatment and/or prevention of meningitis and tuberculosis—is rendering citizens less susceptible to coronavirus.

While the world’s leading epidemiologists are still testing the veracity of these hypotheses, the prevailing discourse around Africa’s comparative COVID-19 infection and mortality rates may be overlooking more practical explanations.

The first is, undoubtedly, timing. The United States and Italy—the two countries most affected by the coronavirus pandemic—registered their index cases on January 21 and 31 respectively. At the time, the global outbreak was still in an early stage, with the disease’s official name not being announced until February 11 by the World Health Organization (WHO). In addition, the US and Italy’s detection of coronavirus within their respective borders came at a time when they had yet to enforce social distancing measures as a means of containing the virus—on top of the fact that the WHO had yet to encourage travel restrictions.

In Africa, however, the continent registered its first case of the virus on February 14 in Egypt, with Algeria being the next state to confirm a coronavirus infection 11 days later. Sub-Saharan Africa only recorded its index case on February 28, when Nigerian epidemiologists confirmed the presence of the coronavirus in an ill expatriate who had entered the country from Milan, Italy, a few days prior. All but three African countries began confirming their index cases as of March, the majority of which detected the presence of the virus after it was declared a global health pandemic by the WHO and movement restrictive measures were promoted. The time lag in coronavirus infections on the continent, means that most African countries had benefitted from global best practices advocated to contain the virus, but may not yet be in the exponential growth phase of their domestic transmissions.

Another factor is epidemiological testing. Despite its need for greater testing, as of April 30, the US was conducting around 19,311 tests per million people of its population. Meanwhile, in Italy, testing had reached around 32,000 per million people. In Africa’s most populous state, Nigeria, testing had reached a rate of 60 per million people, with just over 12,500 epidemiological tests conducted for its estimated 200 million people.

Nigeria is not alone in its poor testing capacity. Available data indicates that all but seven African countries have yet to reach the 1,000 per million test mark as of May 4, with more than half registering testing rates below the 500 people per million. Based on current testing capacity, there is a high probability that the degree of coronavirus infections across the continent is being underreported.

Poor testing capacity also raises questions over whether African countries actually are better prepared to manage the coronavirus pandemic as has been suggested. As per the Global Health Security Index (GHSI)—which provides a benchmark for health security and related capabilities across the 195 countries—more than half of African states were listed in the “least prepared” category to manage disease outbreaks. In fact, out of the 72 countries designated by the GHSI as being least prepared to manage infectious disease outbreaks, 33 were African states.

Moreover, while African governments have significant experience in managing outbreaks of certain diseases such as Ebola virus disease (EVD), they are less adept at addressing Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) diseases under which COVID-19 can be categorized. This assessment was highlighted by the New York Times which undertook an investigation to determine the number and distribution of ventilators on the African continent, given the preponderance of the use of such devices in the management of coronavirus infections. As per its findings, there are around a total of 2,000 ventilators to serve public hospitals in around 41 African countries on the continent. At least 10 African countries had no working ventilators. In contrast, there were 170,000 ventilators in the United States.

Comparatively low numbers of coronavirus infection and fatality rates may ultimately indicate that the continent is basking in the calm before an impending storm. An April 17 statement by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) reinforced such concerns, and suggested that coronavirus infections across Africa could rise to around 122 million, of which 300,000 could be fatal. The figures were presented by UNECA as a “best-case” scenario for the continent. While the evidence does give a grim outlook, it should also galvanize action across African countries to avoid an even worse outcome.