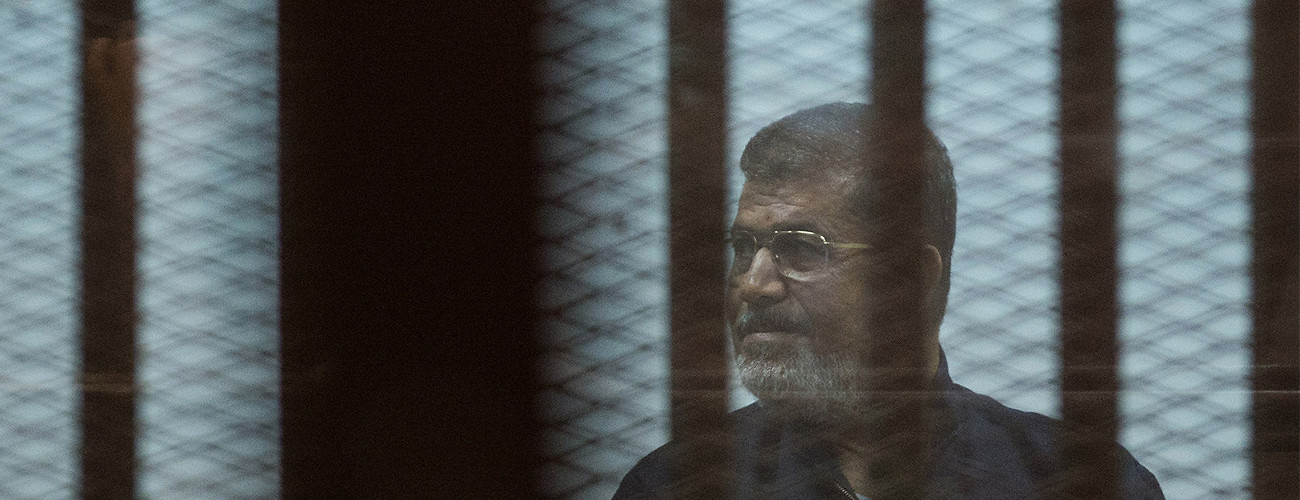

Egypt's ousted President Mohamed Morsi is seen behind defendants' cage on a court in Cairo, Egypt, on June 16, 2015. (Xinhua/Pan Chaoyue/Flickr)

This week a Cairo court postponed its final ruling on a death sentence handed to former Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi and more than a hundred others implicated in a 2011 prison break. As significant as the initial punishment was, it was not much of a surprise. It was a logical conclusion to a highly politicized trial, which was in turn part of a larger scheme to consolidate current president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s position as the country’s uncontested and legitimate ruler. Nonetheless, if the death sentences proceed as planned, they could lead to further instability in the country, including the reinvigoration of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood.

In an atmosphere of intense nationalism, the judiciary, filled with anti-Islamist judges from the era of Morsi’s predecessor Hosni Mubarak, seized the opportunity to take on the Muslim Brotherhood in its May 16 sentencing decision. The arbitrary way in which the judges approached their duties and their repeated rejection of reform to create more impartiality could, however, ultimately become their undoing. This would be particularly likely if they, along with Sisi, lose the support of large parts of the Egyptian population and media.

When Sisi ousted Morsi in July 2013, he found a natural ally in Egypt’s judges, who had been locked in a battle with the Brotherhood over the judiciary’s independence during Morsi’s short tenure. Morsi’s November 2012 constitutional declaration had put himself and his edicts beyond the reach of the judges, effectively nullifying their authority. In an effort to keep the judges by his side, Sisi in turn downplayed calls to reform the judiciary and repeatedly emphasized that he could not intervene in judicial affairs. Not only did this reassure the judges that their interests were protected, and secure their allegiance, it also gave them a green light to take on the Brotherhood and its supporters, alleged or otherwise. In a matter of weeks, the judiciary became willing executors of the state-sponsored policy of denouncing all shades of Islamism as an illegitimate conspiracy that was alien to Egyptian society.

An increasingly politicized judiciary with a decreased sense of impartiality is obviously not conducive to delivering the democratic development long desired by large parts of Egyptian society. Nevertheless, the judges continue to enjoy support from the public, and particularly the media. The mass sentencing of Brotherhood leaders and their sympathizers to death was evidently intended as a populist move on the part of the political establishment. Many Egyptians who rebelled against Morsi’s presidency in the summer of 2013 interpret the recent verdicts as an expression of justice, and an endorsement of Egyptian governance under Sisi.

There are several reasons for this. First, while many remember Morsi as Egypt’s first democratically elected civilian leader, a significant number of Egyptians and the political elite see him as an undemocratic and unjust ruler. Second, many Egyptians also subscribe to the official narrative that the Brotherhood hijacked the 2011 revolution for its own ends and threatened to turn the country into a dogmatic Islamist state. Consequently, symbols of the state, from the police, to the military to the judges, have become sacred. It is no coincidence that these symbols have come under frequent attack by various Islamist groups in recent months, particularly in the Sinai peninsula, which has only entrenched public anger against those groups and intensified calls for swift and severe punishment.

Meanwhile, those with reservations about the current political and judicial landscape refrain from expressing their views due to the fact that dissent in Egypt today amounts to treason. The majority of Egyptians are also tired of revolution and desperate for order once again, no matter the cost. They too give tacit or explicit approval to a government that talks about enforcing the law and getting Egypt “back on track.”

Despite its current popularity, however, the judiciary does not enjoy an ingrained respect among the public as a political institution capable of delivering justice. Its support is primarily political—based on shared anti-Islamist interests—and does not come out of a conviction that it is a properly functioning branch of government. This sets the stage for disillusionment down the line, a loss of faith in Sisi and the regime, and the threat of future Egyptian instability.

Without the widespread suspicion of the Muslim Brotherhood and its allies, confidence in the judiciary would likely weaken significantly, the judges’ lack of impartiality could become a problem, and the state could lose an important link with the people. The situation therefore exposes a problematic preoccupation with chasing Islamist boogeymen, which could jeopardize ongoing attempts to restore order and restart the national economy.

Under these circumstances, the more that people come to realize that justice is still not a guarantee in post-Morsi Egypt—even for those outside the establishment who do support the regime—the more likely they will turn against the judiciary again. If there is one truism about Egyptian politics in recent years it is that public opinion can change without warning. Sisi’s govermment could easily find itself in a position where it is struggling to maintain the confidence of the masses, as well as rein in an independent judiciary accustomed to manipulating the legal system for its own interests.

The most significant unintended consequence, however, is that current policies may again legitimize the Brotherhood, and resurrect it as a viable threat to state interests. In spite of all attempts to discredit its members, the Brotherhood has been working hard to establish a narrative in which it is the victim of a grave injustice. This would only gain value if more people became disenchanted by Sisi, his regime, and a system where justice remains a hollow, unreachable goal.

Thus, instead of simply allowing Morsi fade away into irrelevance, sentencing him to death could run the very real risk of unwillingly imbuing the former president with significant political meaning, potentially even turning him into a martyr. Under these circumstances, how would Sisi rein in the people, the opposition, and any potential bloodshed? Given the regime’s disposition toward heavy-handedness, the answer is not likely to be positive.

It is still difficult to say with any certainty whether Morsi and the other prisoners will be executed or not. If the punishments do go ahead, they threaten to introduce a particularly dangerous precedent. The verdict itself may be reduced to a life sentence on June 16, when the court is due to receive the recommendation of Egypt’s Grand Mufti on whether the punishment falls within the bounds of Islamic sharia law. Nonetheless, it is clear to many that Sisi and the judiciary are not considering the long-term political ramifications of their current actions.

Amr Leheta is a Research Associate in Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.