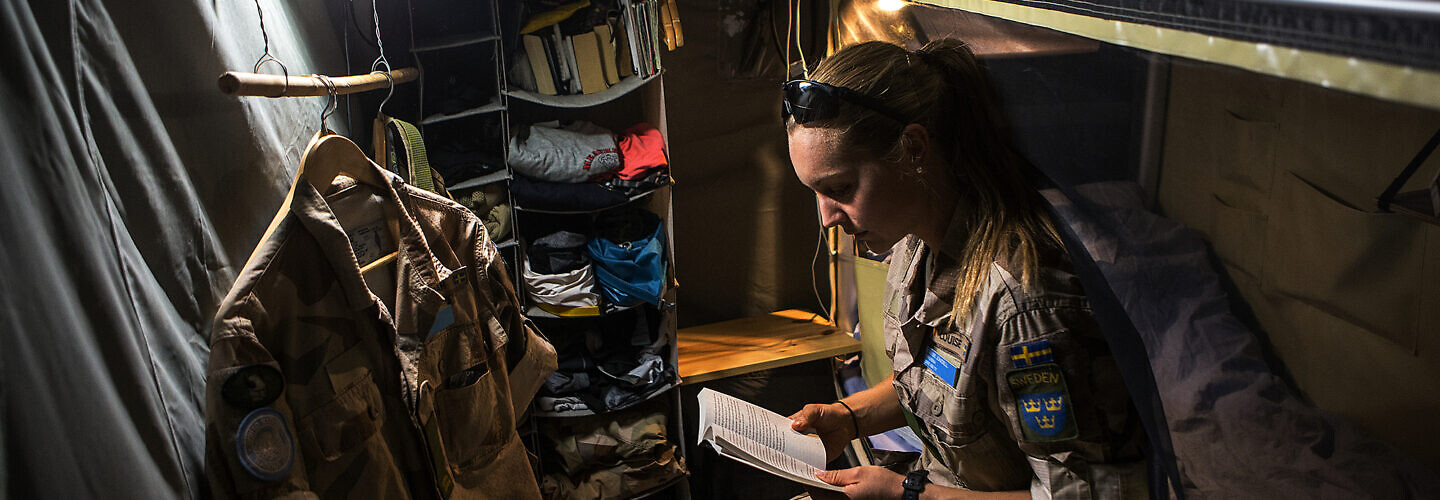

A Swedish peacekeeper serving with MINUSMA reads a book during downtime. (UN Photo/Harandane Dicko)

It would be easy to skip over the technically detailed negotiations of the United Nations (UN) Contingent Owned Equipment (COE) manual, which took place in January of this year. Yet the COE manual plays an important role in meeting goals set in the Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy, as data shows that women peacekeepers face particular obstacles in participating in peace operations due to the fact the peacekeeping missions were implicitly designed for men’s participation.

For example, a woman police peacekeeper noted that, given her remote location, she faced challenges in finding sanitary products (women cannot carry a year’s worth of such products due to limits on allocated luggage). These types of logistical considerations create an unnecessary burden for women peacekeepers. Another challenge is equipment. In one study on women deploying to UN peace operations, 109 out of 142 respondents raised the issue of ill-fitting equipment, which prevents women peacekeepers from fully and safely participating in UN peace operations. A third example is that, while there has been a recognition of the urgent need to ensure that healthcare provided to peacekeepers is gender-responsive and recognizes the health needs of all genders of peacekeepers, it has been used as an excuse by some troop and police contributing countries (T/PCCs) to not deploy women to peace operations. While there are other structural barriers that inhibit women’s full and meaningful participation in UN peace operations, the barriers listed here can be addressed in part by standards set in the COE manual.

The COE manual is negotiated every three years by the COE working group, which is comprised of approximately 20 member state representatives. The updates this year demonstrate small changes that T/PCCs, UN headquarters, and peacekeeping missions can make to begin building more receptive environments for women peacekeepers. This fits with the stated goal of the COE system—to reduce the administrative burden on T/PCCs and other key stakeholders in peace operations; standardize reimbursement rates so they are equitable across T/PCCs; and apply common standards to the equipment and services provided to police and troops.

The COE working groups break the manual into sub-working groups based on three topics: self-sustainment, medical, and major equipment. To address gender biases and flaws within peacekeeping missions, the COE working group focused on revising language in the self-sustainment and medical chapters of the COE. (This included revisions to the model Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). The COE manual will be officially updated when the 5th committee adopts the recommendations, and they are authorized by the General Assembly.

The revisions to the COE related to self-sustainment focused on accommodations, general workplace environment, and supplies provided to soldiers and police. One revision was to the considerations in designing accommodations to ensure the United Nations account for “gender-parity considerations to increase the number of women peacekeepers.” Other revisions focused on specific components of accommodations for peacekeepers such as ensuring laundry facilities allow for sufficient privacy and that both men and women had equal access to recreational activities. Another key revision focused on ensuring dignity and hygiene in ablution (body washing) facilities by having plumbing and fixtures that provide privacy and support the proper disposing of menstrual products.

Another set of updates relates to the gender-specific needs in soldier and formed police unit (FPU) kits. In particular, the revised language specifies that the soldier and FPU kits must be compiled, “taking into consideration physiological differences between men and women personnel, including sizes.” This revision is essential because, despite the fact that equipment such as body armor is meant to be “unisex,” in reality, “unisex” equipment designs are based on male anthropometric data.

Other important COE revisions were to the model MOU. The MOU is a key component of the COE manual, serving as the legal agreement between the United Nations and T/PCCs. It determines details such as the number and type of personnel to be contributed; associated equipment and services; and standards for personnel. Chapter 9 of the COE manual contains generic text for the MOU approved by the General Assembly, known as the model MOU.

The model MOU previously stated that military and police peacekeepers deployed from T/PCCs will never commit harm to members of the “local population” or be abusive or uncivil to “any member of the public.” However, left out of these standards was the treatment of fellow UN personnel. A 2022 report focused on the sexual harassment, discrimination, and assault of UN peacekeepers recommended that memoranda of understanding between the UN and T/PCCS should be more explicit around preventing sexual abuse of peacekeepers. The latest revisions to the model MOU get closer to this standard by noting the prohibition to commit any act that would cause harm not only to the local population or the general public, but also to UN personnel.

Updates to the medical section of the COE manual were also critical, and detailed specific medical requirements for personnel. For example, the revised language notes the requirement for level 1, 2, and 3 medical facilities to have “drugs for common gynecological conditions,” and “menstrual products (sanitary pads).” Being explicit about issues affecting women’s bodies like menstruation is an important first step to changing the narrative so that peacekeepers’ physiological processes are not seen as a burden or stigmatized.

While the COE is a specific process, the discussions it raises can be viewed in light of a broader need to demonstrate that the UN and TCCs are accountable to peacekeepers by ensuring they are prepared and supported in their deployment. And it’s worth noting that the COE guidelines are enforced through various reporting mechanisms as well as periodic inspections throughout the mission lifecycle. There is a greater likelihood of compliance with the standards given that reimbursements are dependent on the inspections. Ensuring standardization is important because when TCCs send formed military contingents, they usually arrive at a mission with their own equipment and self-sustainment services and later get reimbursed under the COE system.

The 2023 COE manual updates do not solve all of the problems faced by women peacekeepers; however, they represent a tangible first step in codifying and standardizing requirements. By ensuring language related to peacekeepers considers and accounts for all genders, it might be possible to slowly transform the image of peacekeepers away from only being men. In the meantime, women peacekeepers will finally be entitled to basic provisions like sanitary pads that they can hygienically dispose of and uniforms that fit them, contributing to their enhanced and safer participation.