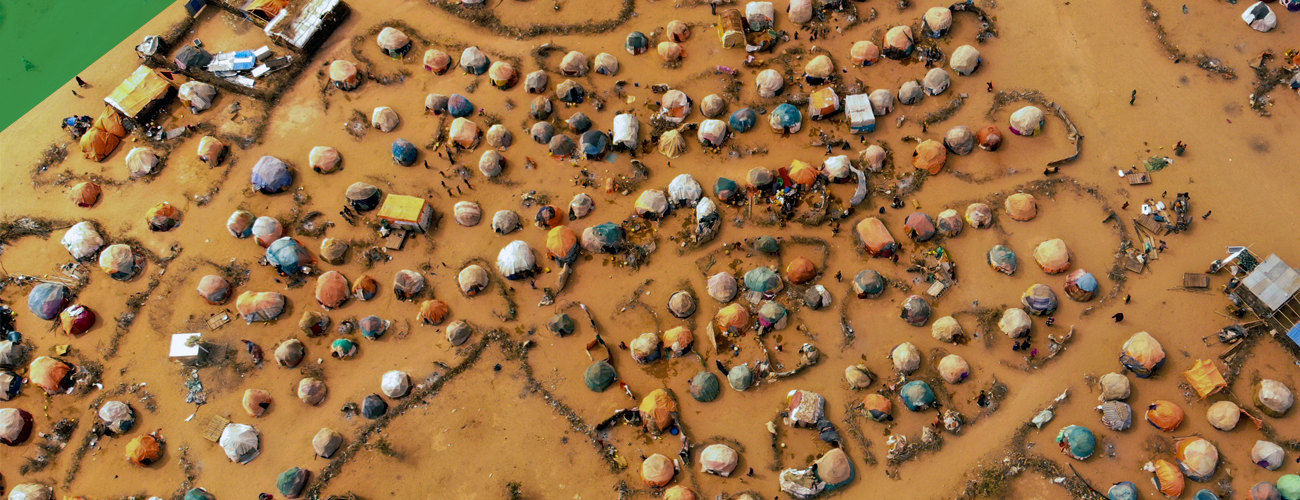

Huts made of branches and cloth provide shelter to Somalis displaced by drought on the outskirts outskirts of Dollow, Somalia, Sept. 19, 2022. (AP Photo/Jerome Delay)

The 27th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP27) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), held this past November in the Egyptian resort town of Sharm El-Sheikh, took place amid a tense global economy and geopolitical outlook. The “polycrisis” of high prices for food, energy, and debt have strained the budgets of all countries, but especially developing countries already under pressure from costs associated with the global pandemic. Indeed, two-thirds of developing and middle-income countries are now in or at risk of default, as Global North central banks raise interest rates to tame inflation and the war in Ukraine further destabilizes global food and oil markets.

Thus, finance was at the top of the agenda for last year’s COP; specifically, finance for loss and damage (L&D). The agreement to establish a fund for loss and damage was a historic win for the Group of 77 (G77) developing countries, but progress on mitigation stalled, leaving 1.5 alive but on life support. This article explores those issues and more, with some thoughts on the road ahead for COP28 in Dubai.

Lots on Loss and Damage, Less on Mitigation

Developing countries have been requesting L&D support within the UNFCCC for years, making the agreement on new funding arrangements for loss and damage a major achievement for the Group of 77. Developed countries have recognized the need for L&D support, including in Article 8 of the 2015 Paris Agreement, and COP27 saw the operationalization of the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage (SNLD), a technical assistance body inside the Warsaw International Mechanism.

But the major headline was the decision to establish a new, dedicated fund within the UNFCCC. This includes a Transitional Committee (TC) of 24 developed and developing countries, which will have its first meeting by March 2023 to work out the new fund’s modalities and sources of revenue. Per the agreement, the TC will present its plan for adoption and operationalization at COP28 in Dubai.

Another important part of the outcome on L&D in Sharm el-Sheikh has not been widely covered. Paragraph 11 of the decision text invites the UN secretary-general to convene the principles of international financial institutions (IFIs) and multilateral development banks (MDBs), to identify how they can respond to countries’ L&D needs. To put this in context: even the UNFCCC climate funds don’t formally allocate money to loss and damage. Paragraph 12 then invites the IMF and World Bank to consider at their 2023 spring meeting the potential for IFIs to contribute to L&D funding arrangements, “including new and innovative arrangements.” This is why the Transition Committee for the L&D fund is set to meet by March: so that their work can inform that of the IMF and World Bank at their meetings in April. In short, the L&D decision at COP27 has created a bridge to link the global politics of climate change, decided by parties at the COPs, with the money for climate change, allocated by the major shareholders of IFIs and MDBs. Thus, the agreement is a breakthrough not only for loss and damage, but quite possibly for global economic multilateralism.

The attention and political capital spent on loss and damage meant that other important issues were overlooked or compromised. Mitigation was one of those issues. The push in years before, including in Glasgow at COP26 to keep 1.5C alive seems to have lost momentum, as calls from around 80 countries, developed and developing, to include in the text language phasing out all fossil fuels (not just coal) was ignored, replaced instead by language on renewable energy. While the text on renewables is positive, it is not nearly enough to limit warming below 1.5C. Governments did agree on a Mitigation Work Programme (MWP) text but it was not ambitious, and some developing country parties described it as “just another talk-shop.” While the goal of the MWP was to “urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation,” most countries failed to increase their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Finance

While the focus remained on loss and damage for the most part, traditional climate finance was still a major point of discussion and contention. The $100 billion per year in climate finance collectively promised at COP15 by the Annex II countries has not been fulfilled, and the negotiation rooms were rife with disagreement about which countries should be contributing. Developed nations tried and failed to include certain developing countries that are major emitters and possess potential to contribute. There was a focus on what the new goal post-2025 would look like, and progress remains to be seen next year in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with eight technical expert dialogues remaining over the next two years. There was criticism of the workings of the GCF as well, with calls to simplify the accreditation process and disbursement of funds, as well as ensure greater longer-term guarantees of such funding.

Finally, what constitutes “climate finance” remains elusive. One of the developing nations voiced concern that climate finance still constitutes loans, which push them further into debt. Another supported the response by suggesting that if loans are considered climate finance, then the repayment of these loans should equally be considered climate finance.

There was a great deal of discussion involving calls to include private-sector finance and the failures of developed countries to enable this funding. To that effect, several events in the pavilions outside the negotiation rooms made progress. Established at COP26, Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero announced at COP27 that it would work with Bloomberg Philanthropies to support a coal phaseout with UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance Mark Carney serving as a special advisor. Furthermore, the African COP delivered the Africa Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI). An ambitious initiative, it aims to produce 300 million carbon credits annually by 2030 while unlocking $6 billion in revenue by 2030 and supporting 30 million jobs.

Egypt delivered strong outcomes on climate finance, but in a grander scheme, these outcomes are moving at a glacial pace. Nations need quicker, fit-for-purpose financing that address their climate financing needs without adding additional burden to their fiscal space.

Global Goal on Adaptation

COP27 was an African COP, and adaptation is a key priority for Africa. However, the Glasgow Sharm el-Sheikh (GlaSS) Work Programme on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) will not conclude until COP28 in the UAE, so there was no clear mandate for a decision on the GGA at this COP. This made the GGA negotiations a bit muddled right from the beginning, as negotiators did not have a clear idea of what the end point of this COP might be on the GGA. Early on, the G77 put forward a proposal for a framework on the GGA, for use both in the next four GlaSS workshops, and on the GGA overall. This framework then became the subject of most of the debate within GGA negotiations, and in the end produced a decision text that still did not offer much clarity on what the next four workshops will cover or how the GGA will be implemented and assessed overall. The lack of progress made in GGA at COP27 was a lost opportunity and increases pressure on COP 28 to produce impactful results.

Four more workshops will take place in 2023, with themes still to be announced. The GlaSS will then conclude at COP28 in UAE, with the adoption of the framework that was initiated at this COP. Because of the very broad nature of the COP27 GGA decision text, there is much work left to be done at these four workshops if the GlaSS hopes to conclude with the adoption of a truly substantive and useful framework on the GGA.

Gender and Youth

After the first negotiations in the early days of COP27, it became clear that the main topic in all rooms would be finance and funding, including in the negotiation room on gender and climate. One objective was to review the gender action plan (GAP) on climate change that is part of the Lima Work Programme on Gender, established in 2014, which aims to advance and integrate gender considerations for implementing the Convention and the Paris Agreement. An area of challenge is the lack of funding needed to implement the GAP. COP27 gave developing countries the opportunity to ask developed countries to fund it, and though an agreement was reached, not all parties were happy, with some arguing that the outcome was not as strong as it should be. Many negotiators also expressed concern about the lack of transparency and process of this negotiation and how the text was agreed upon.

Youth engage in the formal process through Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE). Under ACE’s action plan, governments agreed to short-term activities in four priority areas, including area C, which calls for “meaningfully including youth in and engaging with them on climate action at all levels and facilitating the inclusive participation of, inter alia, children, women, indigenous peoples and persons with disabilities, in climate action, according to national circumstances,” for which governments and relevant organizations are responsible. For many young people who were part of the negotiation, this was a major achievement, and was also notable for being one of the first negotiating texts agreed upon at the first week of COP27, before governments reached agreement on other issues such as mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage.

The Road Ahead

For the first time since it was agreed upon in the Paris Agreement, there will be a global stocktake (GST) during COP28, a process (to happen every five years) which aims to evaluate progress on the implementation of the Paris Agreement. The first technical dialogues took place at COP27, where discussions focused on how governments and non-state actors can address the gaps in climate action. While discussions—which include not only governments but also a diverse range of participants from a variety of sectors—were rich, it remains unclear what the outcome will be for the GST. The third and final technical dialogue is expected to be held in Bonn, Germany, with a political discussion to take place at COP28 in 2023.

Parties will face a heavy workload in 2023, and several questions remain unanswered. These include how to design the L&D fund so that it can provide adequate and predictable support to affected countries in time for COP28; how to bring back to the center the call to limit emissions to 1.5C and to hold governments and the private sector accountable for their commitments; and how to agree on a Global Goal on Adaptation that is inclusive of both developed and developing country priorities.

While the decision on L&D was a breakthrough, the details the TC will have to discuss will determine whether or not the fund is a transformational platform for climate finance or just another fund. It remains to be seen how open the parties to COP are to link their work with the major IFIs and to use this opportunity to connect the need for climate finance with the wider financial flows, mechanisms, and innovative sources. Per the decision text, the TC will make recommendations on institutional arrangements, funding sources, and other questions by COP28, where the parties are expected to adopt an agreement operationalizing the new fund.

While L&D will remain front and center for COP28, other aspects on adaptation will have to be more in the political agenda, including the GGA. The GGA has the potential to provide a new vision on adaptation, one that builds resilience, empowers communities, and recognizes the transboundary nature of adaptation.

Finally, action on L&D cannot and should not be a trade-off for mitigation. Limiting 1.5C is a moral imperative and is at the core of the survival of many countries. The call to end fossil fuel production and expansion should remain high in the UAE, home to 10 percent of the total world supply of oil reserves and the world’s fifth-largest natural gas reserves. The UAE president of COP28 will no doubt be under pressure from governments and activists to demonstrate its commitment to transitioning its own economy away from fossil fuels.

This article is part of a series that examines various topics related to climate change.

Olivia Fielding is Program Coordinator for Peace, Climate and Sustainable Development at the International Peace Institute (IPI). Michael Franczak is Research Fellow with the Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development team at IPI. Masooma Rahmaty is Policy Analyst with IPI’s Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development team. Aparajita Rao was IPI’s Global Initiatives Intern. Jimena Leiva Roesch is Director of Global Initiatives and Head of Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development at IPI. Michael Weisberg is Non-resident Senior Adviser at IPI.