A wide view of the Security Council meeting on the situation in Colombia, January 20,2022. On the screen is Luz Marina Giraldo, Former FARC-EP combatant, signatory to the Peace Agreement and leader in reintegration initiatives. (UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe)

At a time when an unprecedented geopolitical crisis has brought the United Nations (UN) to a boiling point, the question of who is allowed a voice in the UN Security Council’s deliberations on international peace and security deserves a fresh examination. One glaring disparity is between men and women. Over the six years from 2015-2021, 70 percent of all invited briefers to the UN Security Council (UNSC) were men. In fact, the issue of inviting more women to brief the Council has increasingly become a matter of contention. However, despite resistance by some dominant permanent member states, the gap has been closing. This underscores the fact that states that take decisive action can contribute to progress in diversifying representation and ensuring women’s inclusion across the spectrum of topics that are debated at the UNSC. Based on new data compiled from public Council meetings minutes between 2015 and 2021, this article examines current trajectories in representation and identifies Council member states that are driving the process.

While briefing the UNSC has always been a male-dominated affair, more women have been included in recent years, a development which came at the same time as an overall increase in the number of briefers. Until the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020, the number of briefers grew from 232 in 2015 to 398 in 2019, seeing increases each intervening year. If we look at 2021, when the Council’s practices started to normalize after the initial impact of the pandemic, the proportion of the 190 briefers came close to 50/50 male-to-female for the first time.

The majority of briefers are representatives of UN agencies, organizations, and operations. This dominance—62 percent—is unsurprising, given that the UNSC seeks to coordinate its work with other UN organs and agencies, and give mandates and directions to, for example, the UN secretariat and peace operations. Still, of UN-affiliated briefers, men dominate; 78 percent were men and 22 percent were women. If the UN Secretary-General’s Gender Parity Strategy, which seeks to achieve gender parity across the UN by 2028, is to be realized, this imbalance needs correcting.

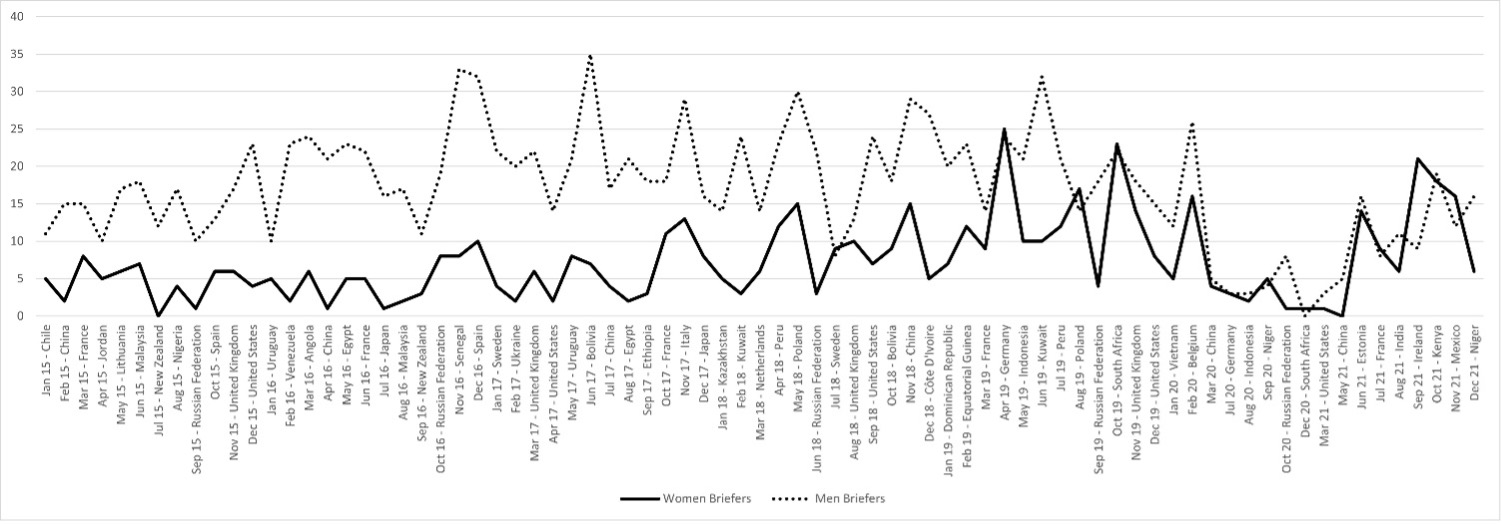

In looking at non-UN briefers, the numbers have grown considerably since 2015, though the gap between men and women is still there for the most part. As seen in Figure 1, the category “other multilateral organizations” (which excludes the UN) mirrors the gender parity of the UN in that there are significantly more male briefers than female briefers. This category, which accounts for 22 percent of all briefers, includes organizations such as the African Union, the European Union, the International Criminal Court, the League of Arab States, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and smaller multilateral organizations.

|

|

Figure 1: Number of external briefers by affiliation category and sex, 2015–2021 (click image to enlarge) |

The only category that comes close to being balanced is “expert institutions,” which encapsulates briefers from policy institutes, universities, laboratories, private organizations, and law firms, among others.

Where are the women? There are three external briefer categories that are more likely to see women briefers than men: “government institutions,” “international civil society organizations” (CSOs), and “national CSOs.”

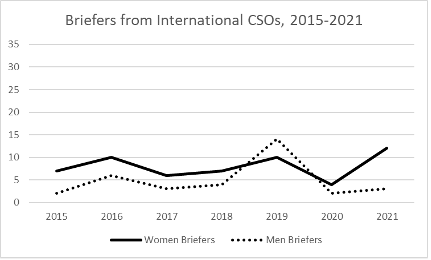

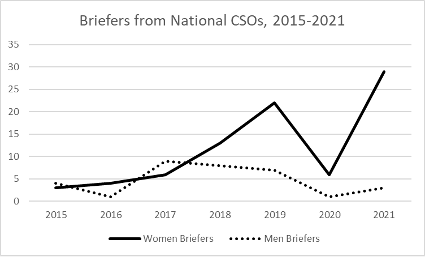

Many of us think of CSOs when we think about women’s representation. This presumption is supported by the data—women make up the majority of briefers from both international and national CSOs when we look at the entire 2015-2021 period, as seen in Figure 1.

The number of CSO briefers has increased over time (Figure 2)—a trend that has primarily been driven by the Council inviting more national CSOs. In 2015, only seven briefers from national CSOs were invited to brief the Council, compared to 32 national CSO representatives in 2021. Despite these gains, briefers from international CSOs account for just 0.5 percent of briefers between 2015 and 2021, while briefers from national CSOs account for just 0.6 percent.

|

|

|

Figure 2: Briefers from International CSOs (top) and National CSOs, 2015-2021 (click images to enlarge) |

What are CSOs invited to brief on? In the period leading up to the 15th anniversary of Resolution 1325—the UNSC’s landmark resolution on women, peace and security—CSOs with the objective of advancing women’s rights and security, in particular, fought to escape being boxed in to brief the Council only at annual meetings on women, peace and security (WPS). Instead, CSOs advocated for the right to be consulted during country-specific meetings which discuss situations directly affecting the participation and security of the organizations and individuals they work with in conflict-affected areas.

The demand has been supported by a number of Council members. Between 2015 and 2021, CSOs were invited to speak on 32 topics. Looking at the data, 2017 was a watershed moment. Prior to 2017, CSOs were primarily invited to brief the Council in meetings focused on WPS, the protection of civilians, and international peace and security. After 2017, there is a notable expansion where CSOs were invited more frequently to provide briefings during country-specific meetings, such as Afghanistan, Colombia, and Yemen. While the diversification of thematic areas is in many ways a positive step forward for diversity and inclusion, we should also note that CSOs continue to be left out of several arenas. For example, there was a lack of CSOs in meetings where peacekeeping was the main point of the agenda.

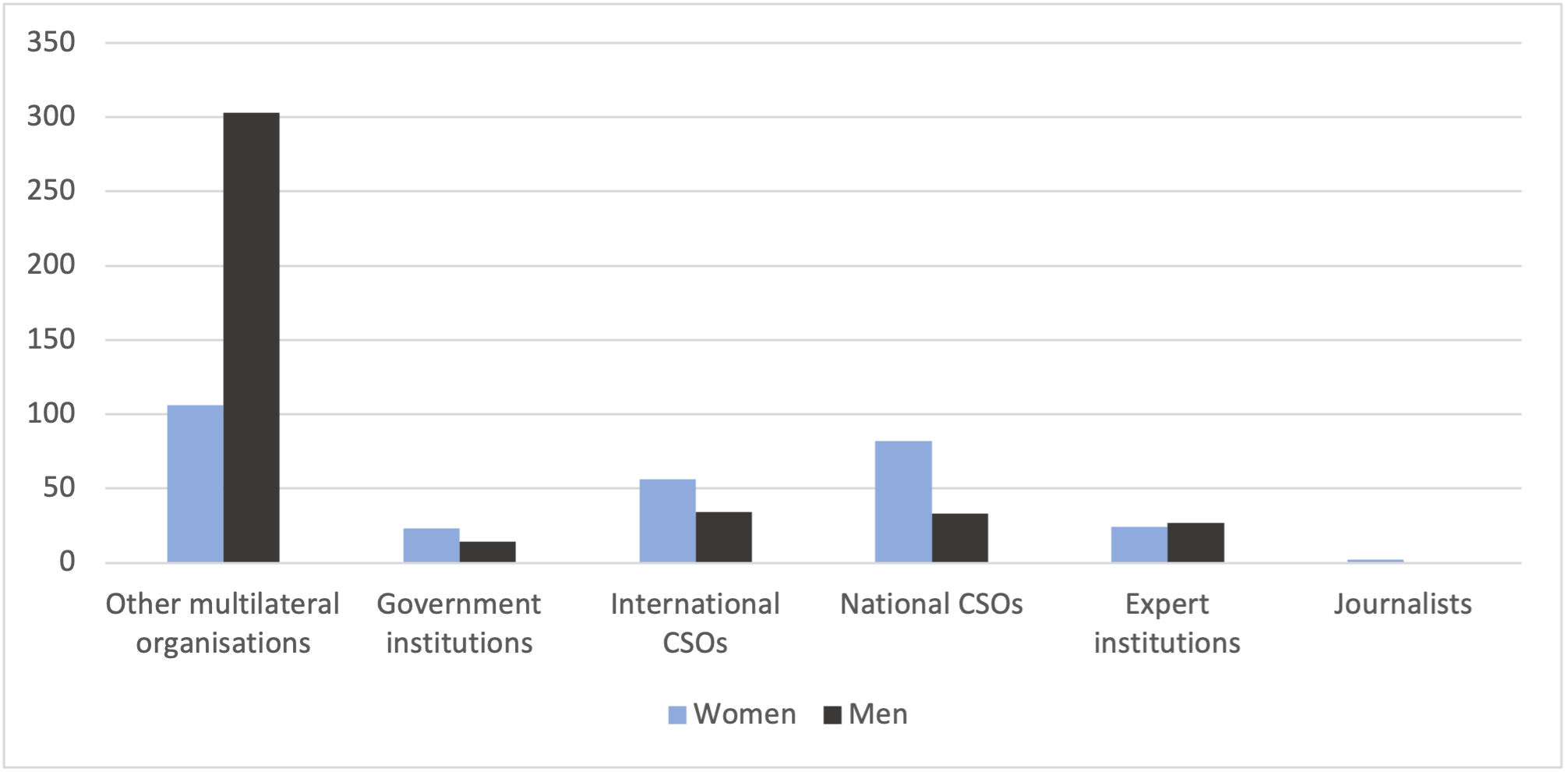

Briefing the Council is by invitation. In selecting who to invite, the Council presidency, which lasts one month, fills an important role. Even though a consensus must be reached among Council members, many states with a gender equality focus have attempted to improve the overall balance of women briefers from all professional affiliations. In fact, the first time 10 or more women briefed the Council during a single presidency was at the invitation of Spain in December 2016. After that, it was not until nearly a year later—in October 2017, when 11 women briefers were invited by France—that having ten or more women briefers in the Council during a single presidency was surpassed.

Looking at Figure 3, we see that those states that tend to have more balanced representation are also states that have clear objectives on WPS for their term in the Council; a trend that lasted into 2022. Notably, in January 2022, Norway’s UN Ambassador, Mona Juul, stated the UN mission’s intention to invite civil society representatives, in particular women, to brief the Council during its presidency. Interestingly, Norway nearly achieved a 50/50 gender balance among the 35 individuals who briefed the Council, with 17 women and 18 men. Similarly, Mexico (November 2021) had 57 percent women briefers; Niger (September 2020), 55 percent; Sweden (July 2018) 53 percent; South Africa (October 2019) 51 percent; and Germany (April 2019) 51 percent. The highest number thus far is by Ireland, which invited 70 percent women briefers during its September 2021 presidency. It is also noteworthy that the presidencies with the greatest proportions of women briefers have primarily been elected members of the Security Council, as these examples show. In comparison, between 2015 and 2021, on average 22 percent of the briefers during Chinese and American presidencies were women; the United Kingdom and France hosted only 34 percent and 35 percent women briefers, respectively. While only 18 percent of briefers during Russian presidencies were women.

In addition to individual country efforts, we see improved collaboration to push representation. Recently, Ireland, Kenya, and Mexico formed the so-called “presidency trio on Women, Peace and Security,” which saw the three missions from three different geographical regions committing to certain actions during their presidencies in September, November, and December 2021. Irish Ambassador Geraldine Byrne Nason described the initiative as “a golden thread” that would run through the presidencies. More specifically, the three countries agreed that, during their consecutive presidencies, they would attain a gender balance among briefers and “strong” representation of women CSO speakers while also making WPS the focus of at least one mandated geographic meeting. True to the agreement, all three invited as many—or more—women briefers as men briefers. Notably, women briefers were present in thematic meetings where women are infrequently invited, such as those on non-proliferation, peacekeeping operations, and small arms. This presidency trio was then followed by a quartet consisting of Niger, Albania, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates, which issued a shared commitment in December 2021.

Figure 3: Women briefers per presidency, 2015-2021, in chronological order (click image to enlarge)

Figure 3 also shows a notable drop in the overall number of briefers, beginning in March 2020. The pandemic disrupted the UNSC meeting schedule as well as the publication of some meeting records. Given some missing data regarding 2020, the information presented here can be understood as conservative, representing the minimum number of briefers, while still providing us with interesting insights.

As the international security debate hardens, there is a risk that we deprioritize issues related to gender equality and representation. But the importance of considering women in conflict-affected countries and women’s roles in ongoing peace operations around the world does not disappear even as the climate in the Council chills. Who is allowed to express views and present facts central to international peace and security can be even more important under such conditions.

Finally, inviting briefers in a way that ensures more balanced and diverse representation requires awareness and conscious actions for a greater good. While we have primarily focused on the gender of briefers and gender parity, a diverse representation in terms of age, race, ethnicity, and physical abilities, including in its intersections, are important not only to create the foundation for decisions in the Council which are based on rich and nuanced information, but for the Council to maintain credibility at a time when the international organization’s legitimacy is being increasingly questioned. The Council has undertaken initiatives to improve representation of women and civil society organizations and to ensure women’s participation in matters of peace and security. If the Council does not walk the talk, the credibility of the Council’s decisions is further decreased.

Louise Olsson is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Anna Marie Obermeier is a Research Assistant at PRIO.