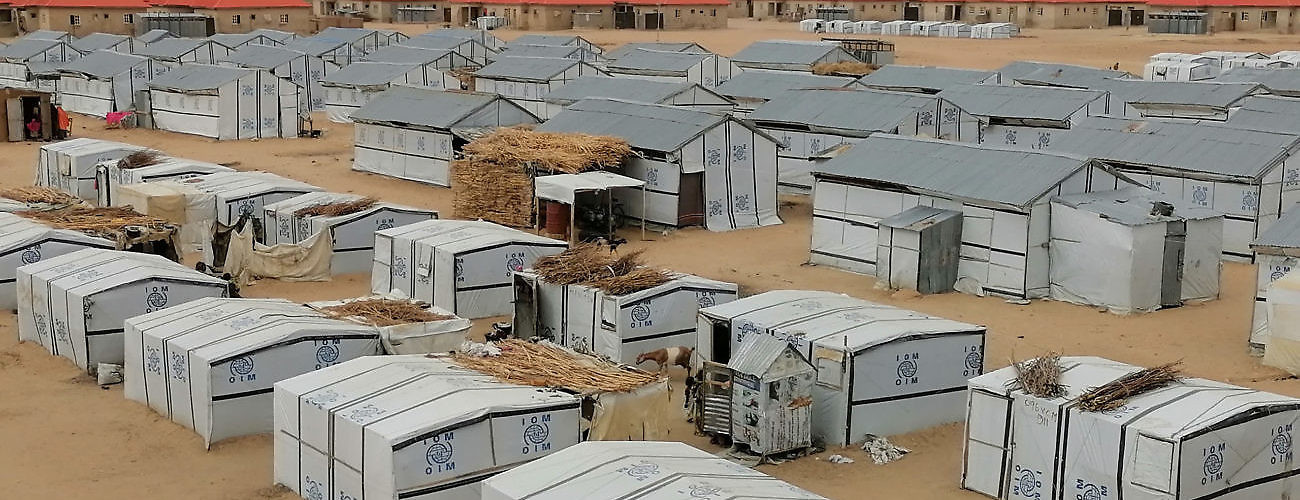

A general view of the Bakassi Internally Displaced People's (IDP) camp in Maiduguri, Nigeria. (AUDU MARTE/AFP via Getty Images)

While the world struggles to address the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, many vulnerable populations are combatting cross-cutting threats to their livelihood, peace, and security. A stark example is in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin regions of Africa, where attacks by violent extremist groups have persisted since March. Violence in these regions is having major effects and presenting challenges for the already overburdened network of camps and informal settlements across the continent.

Extremist Violence and Displacement

The effects of the pandemic on conflict in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin are varied. Early in the pandemic, warnings were raised that groups like al-Qaeda, al-Shabaab, and the Islamic State (ISIS) would use it to further their agendas and make calculated advances. While the frequency of attacks has not dramatically increased, extremist groups’ patterns of violence, cross border movement, and strategic strikes have contributed to an exacerbation of negative displacement trends in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin.

In the Lake Chad Basin, conflicts in northwest Nigeria are drawing interest from both ISIS and al-Qaeda abettors in the Sahel. Images released by the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), for example, show the group carrying out recruitment missions across the Lake Chad Basin Region. The al-Qaeda affiliate group Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen (JNIM), based in Mali, has also increased its cross-border operations. Already destabilized by armed conflict, and with governments and peace operations diverting their attention to pressing public health needs, these actions by extremist groups are not being met with the force necessary to contain them.

The impact of these activities on displacement is concerning. In Burkina Faso, 25,000 Malian refugees were targeted by armed groups in April 2020, leading to a major flow of refugees back into Mali. As of June, 921,000 people were forced to flee from Burkina Faso (a 92 percent increase since 2019). In Niger, a major regional host of refugees and asylum seekers, a series of terrorist attacks forced 489,000 people to flee (including Nigerian and Malian refugees). In Mali, the number of internally displaced people (IDPs) was reported to be nearly 240,000 as of June 2020.

Existing conflict and governance related issues—which have forced over 25 million people to be forcibly displaced across Africa—have made the pandemic’s impact worse, exemplified by the location of refugee and IDP camps. Many of these camps are in border areas which adds a layer of health risk to all cross-border movement during the pandemic. The three-border area shared by Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger is just one site of special concern. For instance, despite efforts by Niger authorities, borders remain porous due to long-standing ethnic and economic ties. As a result, Malian refugees continue to regularly traveling back and forth. At the same time, military operations carried out by the Group of Five Sahel (FC-G5 Sahel) and the French operation Barkhane are seeking to push armed extremists back in this region. However, governance-related issues and conflict have made the necessary political solutions that could curtail extremist group’s activities difficult to implement.

These events are causing displaced persons to settle in camps that were already under-equipped to provide healthcare and are now dealing with COVID-19. Some camps are host to tens of thousands of people, making social distancing in line with mitigation protocols near impossible. While some formal camps, for instance those operated by the National Emergency Management Agency in Nigeria, are making efforts to ensure regular COVID testing, many camps in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel lack the capacity to do so.

Compounding the above challenges is that those displaced also face mobility issues. Border closures and temporary halts on asylum claims have severe consequences for those attempting to flee conflict zones, both in Africa and elsewhere. Uganda, host to 1.4 million refugees, announced regulations for asylum seekers, including a suspension of the reception of new asylum seekers. In Italy, immigration offices have been reassigned to carry out pandemic-related duties. While these actions are being taken as precautionary measures, they pose a serious threat to the international right to seek asylum.

Responses and Role of the African Union

UN entities, international and regional organizations, and the African Union, have all taken at least initial steps to respond to these challenges, though with some complications. For example, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and its partners across Africa have responded, but these organizations are economically overstretched and are operating within pandemic-related restrictions, such as border closures, that complicate their mandates.

Another example is the International Organization for Migration (IOM) which has been monitoring the pandemic’s effect on displaced populations closely and has been filling in some key capacity gaps. In Bakassi camp in Nigeria, they helped facilitate the movement of an IDP with COVID-19 to an isolation center to curb transmission. IOM has also built self-quarantine units in the displacement camps of Gwoza and Pulka.

The African Union’s Peace and Security Council (AUPSC) has called particular attention to the issues being faced by refugees and IDPs during the COVID-19 pandemic, outlining next steps for national, regional, and international actors. The AUPSC noted in April the strong negative impact COVID-19 will have on refugees and IDPs. Other responses have come from the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights and through a leadership meeting attended by the head of the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), the Lake Chad Basin Commission secretariat, the head of the Multinational Joint Task Force, and the Regional UN Sustainable Development Group.

While these are positive steps, responding to extremist violence and displacement-related issues will depend on decisiveness and more significant coordination at the regional and continental level. To this end, there are a few next steps that can be taken by the AU and its member states to mitigate harm.

Ceasefire and Long-Term Planning

As ongoing armed conflict exacerbates displacement on the continent, it is crucial that all relevant parties commit to continuing the global ceasefire called by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, and AU Commission chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat.

In terms of planning, regional actors have been responding to the security and humanitarian concerns raised by the complicated landscape for some time. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) developed a 2020-2024 action plan to end terrorism in January which has the potential to guide some necessary political responses to mitigate extremist groups effectiveness in the long-term.

Additionally, consultations between experts of the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCGC) and the African Union Commission (AUC) resulted in a comprehensive Regional Strategy (the Regional Stabilization, Recovery and Resilience Strategy for Areas Affected by Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin Region). It is imperative that international partners support these initiatives as the destabilizing effects of extremism in both the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin regions cannot be curtailed with military intervention alone.

At the same time, the AU should continue to prioritize regional political cooperation, which will be critical for long-term stability.

Borders

The issues around borders are of particular concern since the movement of people and necessary goods and supplies pose COVID-19 related risks, however borders must not be closed to those seeking asylum. The AU, UNHCR, IOM, and governments should work together to establish protocols that protect civilians from increased COVID-19 transmissions and limit unchecked border movement that contributes to human trafficking, smuggling, and transnational crime, while ensuring the rights of asylum seekers is taken into consideration.

Governments can provide support by equipping border authorities with the necessary tools to augment COVID-19 preparedness—e.g., by screening travelers—while also developing new solutions to border issues, such as the border assessment and border authorities training program taking place in Mali.

Healthcare

COVID-19 poses a host of novel challenges and governments should respond to these challenges by ensuring that all people, especially the ones belonging to the most vulnerable groups, are protected. In this regard, national health services being accessible to both nationals and refugees is essential, and security forces temporarily suspending rotations and prioritizing medical care on military bases will help curtail outbreaks. With the precarious conditions of many refugee camps, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and continental entities such as the Nigerian Red Cross can play a significant role in supporting measures that can respond to a possible large-scale outbreak.

The challenges of displacement and extremism in sub-Saharan Africa are not novel, but the COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating them and exposing operational weaknesses in response. If COVID-19 is an “existential serious threat to international peace and security” as stated by the AUPSC, it will require comprehensive and cooperative response that ensures those in need of protection are protected.

Ilhan Dahir is an intern in the Center for Peace Operations at the International Peace Institute. Her research focuses on migration, human rights, and extremism.