Wide view of delegates at the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development meeting on voluntary national reviews in July 2018. (UN Photo/Rick Bajornas)

This year’s High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) in July will mark the fourth follow up and review of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As in every year, there will be a few of the agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under review and some member states will present their Voluntary National Review (VNR) on the progress they are making in implementing them. Notably this time around, Palestine became the chair of the Group of 77 for the first time in UN history. As member states previously decided that every four years the HLPF would be held twice, the forum in July at the Ministerial level and convened by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) is the first, and will be followed by the head-of state level SDG Summit in September, convened by the General Assembly.

While HLPF continues to be a place for high-level discussions on the 2030 Agenda, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has acknowledged that the current geopolitical landscape is not enabling achievement of it, saying that “the commitment to multilateral cooperation, so central to implementing our major global agreements, is now under pressure.”

In response to this adverse environment, the HLPFs in July and September should be viewed and approached as opportunities and fora that can contribute to action towards the collective implementation of the SDGs. To better understand how this can be achieved and the context of 2019, there are four questions worth exploring: why is HLPF 2019 important? Where are we in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda? What are the concerns on the “peace goal,” SDG 16? And, what do we want and need to see at HLPF?

Why is HLPF 2019 important?

This year’s HLPF completes the first cycle of review of all 17 SDGs, i.e., all the goals will have been reviewed by the end of 2019. The goals under review this year are also the most difficult to be examined, particularly the goals on inequality (SDG 10), peace and inclusion (SDG 16), and climate change (SDG 13). These are the “misfits” SDGs that were the most controversial and difficult to get member states to agree on, and they are not the bread and butter of the development system. Perhaps this is why member states also decided to leave them for review at the end of the cycle.

Additionally, the reform of the UN development system (UNDS), including the reinvigorated resident coordinator (RC) system, took effect this year. Under this new system, RCs have now been separated from the UN Development Programme (UNDP) or other UN agencies, and their role has been expanded to make them the “highest-ranking development representatives of the United Nations development system.” With this comes a mandate to achieve the 2030 Agenda and respond directly to the secretary-general. The empowerment that RCs now have, along with the added responsibility, is an opportunity and challenge for implementation of the agenda.

The new UN structure at all levels is also supposed to directly respond to the 2030 Agenda and report to the new departments at UN headquarters, and at regional and country levels. In his recent report, Secretary-General Guterres suggested the creation of a Funding Compact between member states and the UN development system that would shift the way the system is funded in order to realize the full potential of the UN as a whole and build trust among its different entities.

This is a huge shift for the UN. It demonstrates the effort being made to have a coherent and single voice at the country level and to try and unify funding structures in order to avoid agencies and departments competing for funding sources.

The format and organizational aspects of the HLPF are also being reviewed this fall on the basis of the two UN General Assembly resolutions that established and clarified the forum. This review represents an opportunity to reflect on whether the current format—based on a review of five to six goals per year—is the appropriate follow-up mechanism for reporting on SDG implementation. This is important, because the current format, albeit pragmatic, means that not all member states present their report on all 17 SDGs. What results are missed opportunities to focus on the interlinkages and provides a negative incentive for member states and others to “cherry pick” the goals that are more “likable” and to be silent on other goals that may be more challenging, such as SDG 16 (peace, justice, and inclusion), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), and 13 (climate change).

Moreover, the VNR process is seen by outsiders as a “talkshop” where only positive results are shown, rather than an honest assessment of where countries are. Yet, parallel processes have developed where countries are learning and discussing more openly their challenges to implement the 2030 Agenda, such as the Partners for Review. It remains to be seen whether these issues will be addressed during the review of the HLPF during the 74th session of the UN General Assembly in the fall.

Where Are We in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda?

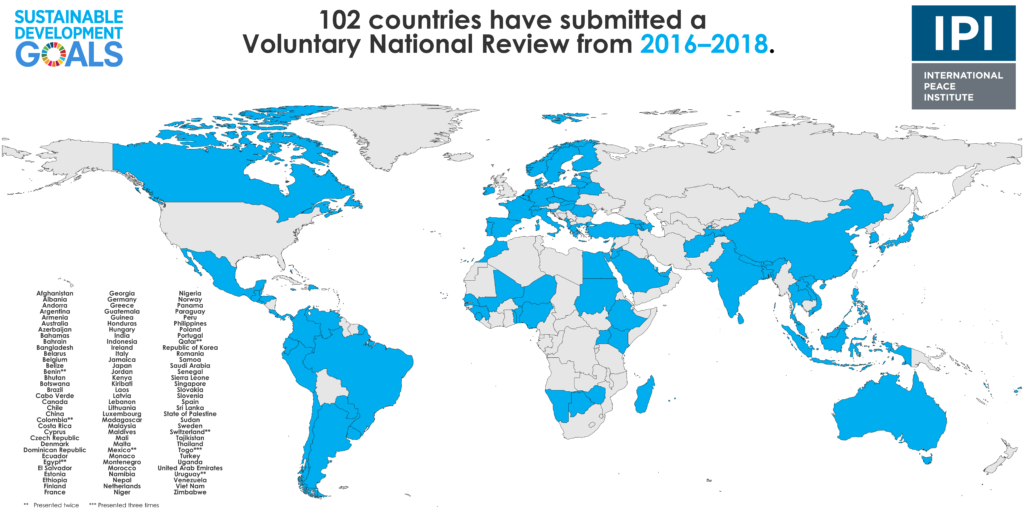

One way to gauge progress on implementation is to survey the data. All 193 UN member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. So far, 102 countries have presented their progress report. Around seven countries have presented their VNRs twice, and Togo is the only country that presented its VNR 3 times. This year, 47 countries plan to present their progress on the SDGs, showcasing the policies and solutions in implementing SDG targets.

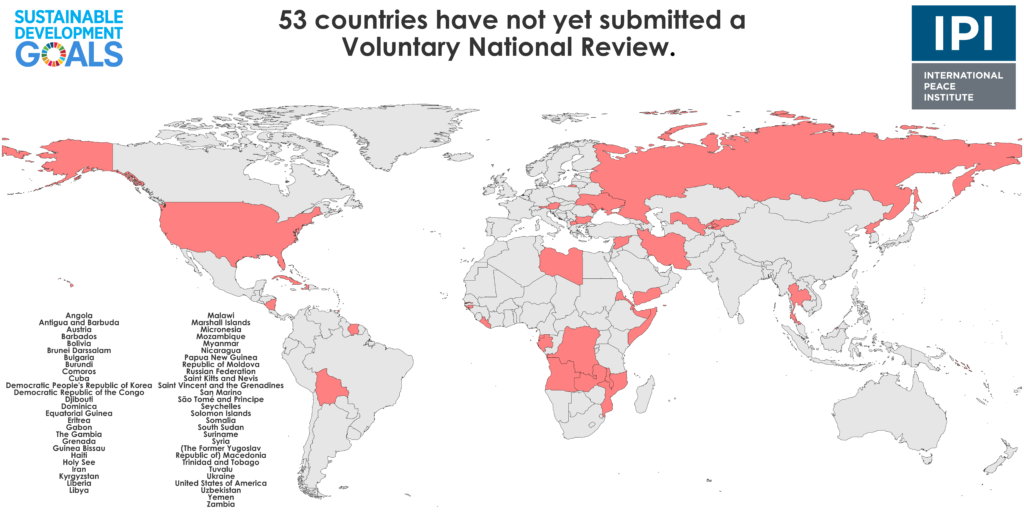

Around 53 countries haven’t presented their VNRs in the first review cycle, including countries like the United States, Iran, Venezuela, and Russia. Secretary-General Guterres released his annual report on the SDGs indicating that “progress has been slow on many Goals, that the most vulnerable people and countries continue to suffer the most, and that the global response thus far has not been ambitious enough.” In order for the SDGs to be achieved by 2030, he emphasized the need for strong political leadership and urgent, scalable multi-stakeholder action for acceleration of the progress.

Challenges notwithstanding, there has been progress, but it has been uneven depending on the region and the goal. Given that national reviews by the governments are voluntary, it is obviously difficult to know about implementation in those countries that do not present. So far, achieving the SDGs by 2030 seems to be a very high bar in a highly polarized political environment.

Moreover, the geopolitical environment makes progress difficult, particularly since the space for human rights work has shrunk, trade disputes between major powers remain ongoing, authoritarianism is on the rise, borders are being closed, and civil society work is being curtailed. Against these odds, the 2030 Agenda remains a unifying platform that is neutral of ideology and can be a force for collective multilateral action.

What Are the Concerns on SDG 16?

For the first time in four years, SDG 16 on peaceful, just, and inclusive societies is going to be reviewed. While this is a moment that the SDG community and especially those monitoring SDG 16 have been waiting for, there is still concern over the securitization of the goal undermining development initiatives. Indeed, including a goal on peace in the agenda was initially very controversial during the negotiations and, once approved, represented a major achievement.

Something that differentiates the SDGs from the Millennium Development Goals is their universality. This universality makes SDG 16 an objective for all countries, whatever their level of development, their politics, or their history. However, SDG 16 is viewed by some as only for countries that are affected by conflict, which has led to mistrust among governments, particularly in the global south. It is time that more developed countries integrate SDG 16 within their national policies and avoid using the goal to promote their national interests elsewhere. Ensuring equal justice for all, and promoting non-discriminatory laws in policies are indeed targets that countries like the US need to implement.

What Do We Want and Need to See From HLPF?

The two sessions of HLPF will have different aims. In July, the focus will be on the review of the goals and presentations of member states, and in September there will be a high-level review at the heads of state level to assess implementation of the 2030 Agenda as a whole. The September session is also known as the SDG Summit, mandated to be held every four years under the auspices of the UN General Assembly.

Unlike previous years where member states adopted a ministerial declaration, this year there will only be a political declaration. This declaration is currently being negotiated under the leadership of Sweden and the Bahamas.

In the current context, what we can expect from HLPF 2019 is not as much as we would like. The political declaration will, at best, reiterate previous commitments and will not reopen any aspect of the 2030 Agenda for re-negotiation. The good news is that Sweden and Bahamas are leading the negotiations. They have been consulting all regional groups and are being very inclusive in the process, and are also managing expectations. They are clear that the declaration will not re-open any previous agreement. Additionally, the President of ECOSOC—permanent representative of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines—has also been committed to making the HLPF more effective and she will present a summary of the discussions.

Moreover, there will be a vibrant range of events around the HLPF that highlight how the 2030 Agenda is not only member state or UN driven, but also has the attention of civil society and the private sector, and has managed to mobilize millions of people. The HLPF of the future should truly be a forum for the people of the world to come to together and celebrate progress, have more honest discussions on progress, and be more inclusive of civil society, entrepreneurs, and innovators at the frontlines of implementation.

This article is part of a series being published by the Global Observatory in the lead-up to the 2019 High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) on Sustainable Development.