MONUSCO troops patrol the villages of Fataki in Eastern DRC following attacks by armed groups. (UN Photo/Michael Ali)

This is a delicate year in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with a general election scheduled for December, two years late, and a lot of unknowns about the resulting aftermath. While Joseph Kabila announced he will respect the constitutional term limits for the presidency, there are still concerns over whether a credible election can be held. It is in this context that the United Nations’ largest peacekeeping in terms of budget and number of personnel, the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO), strives to execute its mandate. MONUSCO has had its own challenges of late—including the security of its personnel, highlighted in the “Cruz report,” and funding cuts—which make it a particularly interesting case study of UN peacekeeping.[1] A closer look at its budget is central to any conversation around the mission’s future.

The Budget Overall

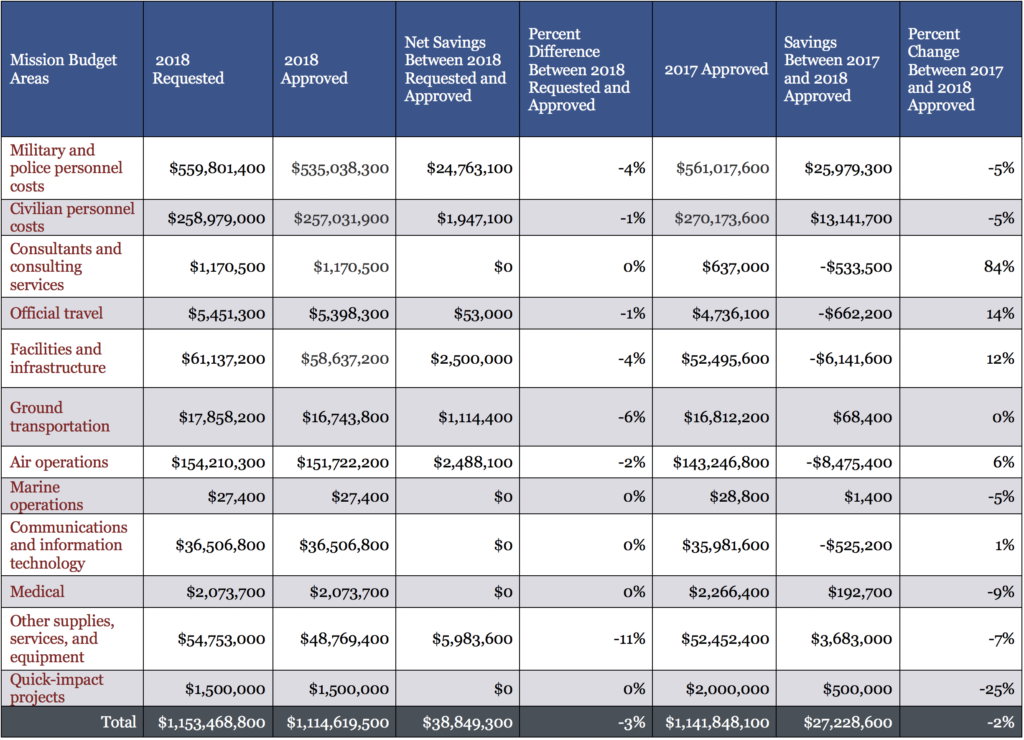

In the lead up to the renewal of MONUSCO’s mandate in March, the Department for Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) requested a $12 million budget increase for the mission. In the end, the budget of MONUSCO was cut by $27 million. From one perspective, the amount cut is relatively insignificant as they represent only around 2 percent of MONUSCO’s total budget, but the finances of the mission are so precarious that it could yet prove costly in the long term.

For its requested budget, there were increases of $11 million on air operations, $9 million on facilities and infrastructure, $2 million on supplies, services, and equipment, $1 million on ground transportation, and a near $1 million for official travel. These are to be partly, but not fully, paid for by an $11 million cut to the civilian personnel budget and a $1 million cut to military and police personnel costs.

The UN General Assembly agreed to the increase in spending on air operations and on facilities and infrastructure, but reduced the raise by $2.5 million in each case, and supported most of the increase on official travel (it also, interestingly, approved a $533,500 increase in the mission’s consultancy budget in its entirety, an 84 percent increase). But the General Assembly refused any increase on ground transportation (instead instituting a small cut), and dramatically reversed the extra amounts on supplies, services, and equipment, instituting a near $4 million cut. And it insisted that personnel cuts go far further, carving an additional $2 million out of civilian personnel costs, and a spectacular $25 million more out of military and police personnel costs.

MONUSCO 2017 and 2018 Budget Totals and Comparisons

Troop Budget Cuts

The final military and personnel budget figure (see table) raises the most eyebrows. As there have been no changes to the total number of peacekeepers mandated—16,215 troops, 391 police personnel, and 1,050 personnel of formed police units—this raises the possibility that the mission won’t be able to deploy its full allocation of troops.

The allocated funds represent a cut of roughly 5 percent. Staff costs are complex, and so it does not necessarily follow that this will translate into the mission being unable to deploy 5 percent of its troops or police—which amounts to roughly 900 personnel, or slightly more than a large battalion—but in the absence of further information we must take that as the upper limit for a potential reduction.

A troop drawdown could cause significant difficulties in the mission. Budget cuts and troop drawdowns in previous years have left force personnel feeling that they are at the absolute limit of their resources, and that any further cuts, unless met by a reduction at least in the geographic area covered by the mandate, would leave the mission unable to prevent a spiral into unmanageability, particularly in the current election context. A recent investigation suggested that there has been a sharp upsurge in violence in the DRC recent months, and that the downsizing of MONUSCO was a contributing factor.

Further, MONUSCO has thus far coped with troop drawdowns via the doctrine of “protection through projection.” The principle is that fewer troops can maintain an equivalent amount of control over a larger area by closing permanent bases and instead having a more mobile force which is able to pop up when required in order to project influence. The strategy has its supporters and its critics, who have two primary concerns.

The first is that, when done properly, it is scarcely cheaper as one spends roughly as much on additional transport as one saves in reduced troop levels. In 2017, transport budgets were also cut, making the policy seem particularly disingenuous. The modest increases to air transportation budgets in 2018 give the policy a greater potential for success, but this must not be taken too far.

Secondly, as various NGOs have warned both publicly and privately, there are real doubts as to whether protection through projection can achieve the same degree of protection as a permanent presence. The absence of permanence renders the mission increasingly reliant on its already vital links to the local community such as Community Liaison Agents (CLAs), Local Protection Councils (LPCs), and Community Alert Networks (CANs). It also raises issues of exposure, protection, and coverage, and wider questions as to if such a network can be effectively supported and developed remotely. Where a network involves people that the UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS) security umbrella—for example CLAs—consider staff, they are not allowed to deploy to an area that UNOPS designate as “red” unless there is a secured UN base in the area. This means that once permanent bases are closed there are no CLAs in the areas where protection is most required. And when a network does not have any such personnel, one could legitimately ask whether its members are being placed at both personal risk and at risk of influence from local armed groups.

If forces are to be further drawn down, the mission must ensure that the decisions regarding which contingents to repatriate are meritocratic. The UN Department for Peacekeeping Operations conducts performance assessments of their various contingents, and is therefore believed to have a comprehensive understanding of relative performance levels. There have been recent efforts to place more emphasis on performance in decisions on troop composition, including by reaching out to additional troop contributors and by rewarding good performance. Nonetheless, there is still insufficient clarity as to the extent to which performance reviews can and do influence force generation, a perception that political considerations take priority, and that UN Secretariat staff are keen to avoid the friction of telling a troop contributing country (TCC) that their contingent is not wanted. In the case of MONUSCO, many felt this resulted in the mission’s Force Intervention Brigade (FIB), widely believed to be underperforming, being unduly spared force reductions.

Increased Air Budget

The increase, albeit limited, in the air operations budget will no doubt be welcomed by MONUSCO. Whether it will be enough, particularly in the context of a contracting ground transportation budget and the domestic climate, remains to be seen.

The DRC, though the size of Western Europe, has only just over 2,000 km of paved roads and helicopters are therefore vital to transport troops in a timely fashion over anything beyond local distances. Helicopter units I visited were operating on such a tight budget that they could allow for scarcely more than an hour’s flying time a day, significantly limiting their efficacy.

Moreover, the largely urban political violence associated with electoral cycles is very different from the current threat, which primarily, but not always, comes from low level and dispersed rural violence. This could greatly alter the level and nature of the need for air operations, an increased budget will at least allow the mission some flexibility in dealing with this reality.

Bases Under Pressure

DPKO requested a 4 percent increase to MONUSCO’s $52 million supplies, services, and equipment budget and instead received a 7 percent cut. On top of the $2.5 million smaller-than requested increase to the facilities and infrastructure budget, this raises concerns over whether more bases will be closed. If so, the doctrine of protection through projection will be further stretched. Will it be possible to maintain bases and keep them safe on this tighter budget?

Less than a year has passed since the Semuliki base was attacked by suspected Alliance of Democratic Forces (ADF) fighters, killing 15 in the deadliest single attack on UN Peacekeepers since 1993. In response to that attack, the UN installed perimeter lighting, upgraded the communications infrastructure, and enhanced the security perimeters at several of its bases. Will cuts to the facilities and infrastructure budget make it difficult to maintain such improvements? The cutting away of facilities and infrastructure funding might also risk creating a hollow force which cannot fulfil its true capability.

Completing the Mission

In the long term, the best and most effective way for MONUSCO to make substantial savings would be to bring the mission towards completion and to thus enable parts of the mission to be withdrawn. This is easier said than done, particularly in the current election context.

MONUSCO, as with many “stabilization” missions, has two core elements to its mandate: protecting civilians and supporting a political process. These two elements sometimes clash, and are likely to come into greater conflict in the context of DRC’s electoral cycle. Further, the fact that peacekeeping—and indeed all UN approaches—is highly state-centric creates additional tensions with respect to both parts of its mandate.

Support for a political process is frequently viewed as support for a sovereign government. But elections call that logic into question as the government ceases to be the exclusive legitimate custodian of political authority and becomes but one actor of many, each with an equal claim to state legitimacy. Further, in cases such as the DRC where state armed forces are the actor most likely to pose a risk to civilians, strengthening military capacity could be seen as undermining the Mission’s Protection of Civilians work.

A strategy of “neutralizing” armed groups also becomes more complex during an election. There are already concerns that neutralizing armed groups amounts to taking sides in a multifaceted and complex conflict—neutralizing one armed group will invariably help that group’s opponents, and confrontations between different ethnic or self-defense-based forces defy the easy identification of preferable victors from the perspective of protecting civilians. Elections complicate these already complicated dynamics given alleged links between armed groups and political movements both directly and indirectly as a result of neighboring countries who are believed to sponsor both armed and democratic oppositions.

These arguments provide a compelling rationale for putting the capacity building aspects of the mandate on hold until after the December election. Instead, and in the context of constrained resources, the mission could concentrate exclusively on the protection of civilians, and attempt to neutralize armed groups strictly on the basis of the risk such groups pose to civilians.

What happens if elections—or their potential further delay—lead to violent confrontations between members of the DRC armed forces and opposition groups? It will be important to have clarity over whether the mission is expected to provide support to the armed forces in maintaining control of opposition areas, and, if so, under what circumstances and with what caveats. Should they withdraw support if the armed forces are the group primarily threatening civilian life, or if their legitimacy as representatives of the host nation is called into question? Would they be required to oppose non-state armed groups in all circumstances, even if an electoral crisis increased their legitimacy or if they were opposing groups who presented a greater risk to civilians? Lessons could be usefully learned from UN missions in Liberia (UNMIL) and Haiti (MINUSTAH as it then was) were presented with difficult and contested elections.

An Exit Strategy or Exit Criteria?

While there may be a coherent rationale for placing the mission’s capacity building work on hold in the short term, the mission does appear to be committed to working with the state armed forces in the long term, as they see it as an integral part of their exit strategy. However, creating the conditions which would enable the mission to withdraw would require steps to be taken by many actors, notably the government itself, not just the mission. Creating those conditions would also require a lot of work which diplomatic, political, humanitarian, and bilateral actors might be better suited to deliver, particularly security sector reform and developmental work. Therefore, there needs to be an acknowledgement that the successful completion of the mission is not entirely in the mission’s own hands, and it may be helpful to think in terms of “exit criteria” as opposed to an exit strategy. The mission would then not withdraw until those conditions are met.

If the Security Council wishes for the mission to withdraw more rapidly, or to at least reduce the size of the geographic mandate, it could consider reducing its state centricity and localizing its objectives. There may be local areas or regions where the local or regional government is able to guarantee rights and security even if the central government is not. By facilitating the development of democratic legitimacy, authority, and security capacity of local and regional governments, the mission could start to withdraw from certain areas of the country at an earlier stage.

Fred Carver is the Head of Policy for the United Nations Association-UK, and has a particular focus on UNA’s work on UN peacekeepers. He has conducted field research in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Israel, and Palestine.

[1] In March, I conducted a short visit to MONUSCO bases in and near Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo as a guest of the mission. The visit gave me a deeper understanding of the mission’s perspective on its work.