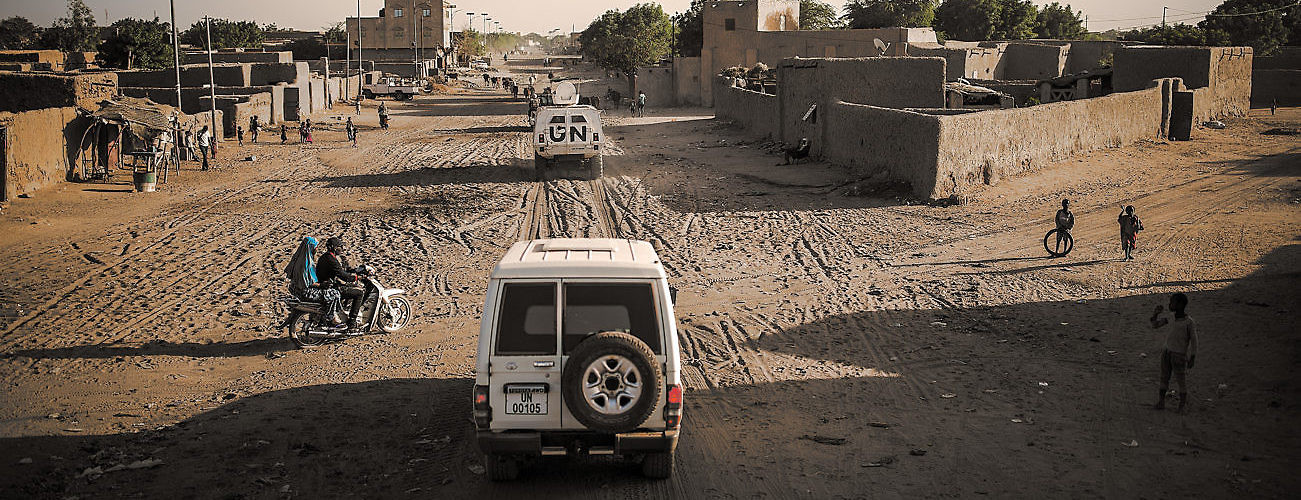

Peacekeepers serving with the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) in the streets of Bara in the Gao region. (UN Photo/Harandane Dicko)

Multilateral reform initiatives can be interesting for one of two reasons. Some generate fresh ideas about how states should cooperate. Others inspire governments to invest politically in pre-existing ideas. It is quite rare for states to act on completely new ideas straight away—even the diplomats who negotiated the United Nations Charter in 1945 cribbed a lot of concepts from the League of Nations.

If the current Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative has any impact, it will be on the “political investment” front rather than in the “new ideas” category. This is not a bad thing. There has been a surfeit of thinking about peace operations in the last five years or so. The 2015 High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) and ensuing studies such as this year’s Cruz report on military aspects of peacekeeping have said pretty much all that needs to be said in conceptual terms.

These studies have also established a reasonably coherent narrative of what UN operations need to do to perform better. This involves: (i) a greater focus on political solutions to conflicts; (ii) a more rigorous approach to protecting civilians under imminent threat of violence; and (iii) more investment in “sustaining peace” (aka peacebuilding) over the longer term. Analysts and officials differ over the exact balance of priorities, and some influential dissenting states such as Russia insist that the UN should stick to traditional visions of peacekeeping. But the politics-protection-peacebuilding triad is now the conventional policy wisdom in New York.

The UN has made some progress in translating this emerging consensus into practice. The secretariat has partnered with the World Bank on funding for sustaining peace. Civilian and military officials in field operations have used the Cruz report’s findings on peacekeepers’ performance to push troops to become more active. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has persuaded the UN membership to endorse a reorganization of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), Department of Political Affairs (DPA), and Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO) that should—bureaucratic politics permitting—boost joined-up thinking at headquarters.

But despite these advances on policy, UN officials and New York-based diplomats still sense that there is a political gap at the heart of the reform agenda.

There is a general recognition that the biggest challenges facing UN operations today—from securing contested election in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to forging a unity government in Libya—cannot be resolved by tweaking operational mechanisms alone. Improving peacekeeping patrols in South Sudan will not be enough to reconcile its perennially divided leaders. As Secretary-General Guterres warned the Security Council in March, UN member states need to give missions more genuine top-level political support to have any chance of success.

This is where A4P comes in. The underlying goal of the exercise is to raise the political profile of the issues raised by HIPPO, Cruz, and other UN reviews to the point where heads of state take notice and invest some real political capital in making UN operations work. On the basis of a series of broad consultations with diplomats in New York this summer, DPKO and the Department of Field Support (DFS) have prepared a set of “draft commitments” for leaders to endorse at a side-event at the UN General Assembly in New York this September. These commitments emphasize all the elements of the politics-protection-peacebuilding triad, under seven headings:

- To advance political solutions and enhance the political impact of peacekeeping;

- To strengthen the protection provided by peacekeeping operations;

- To improve the safety and security of peacekeepers;

- To support effective performance and accountability by all peacekeeping components;

- To strengthen the peacebuilding impact of peacekeeping;

- To improve peacekeeping partnerships (with the African Union, etc.);

- To strengthen the conduct of peacekeeping operations and personnel.

So far, so familiar: some lines are pulled from earlier UN documents. But conceptual innovation is not the point. Getting top-level political buy-in is. There is a long history of member states endorsing peacekeeping reform proposals in principle, but then failing to follow up politically in practice. The September A4P summit offers a platform for leaders to recognize their responsibilities for UN missions, at least rhetorically.

To this end, Secretary-General Guterres—a former prime minister with an instinctive sense of what senior political figures can consume—has insisted the commitment statement should be brief. The current draft runs to three pages. Will leaders buy it?

The notion that prime ministers and presidents should devote much time to public discussions of UN peace operations is quite a recent one. The Security Council convened at a heads of government level for the first time in 1992 and requested Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali to draft his “Agenda for Peace.” But this was mainly because Council members thought it necessary to invite Russian President Boris Yeltsin to New York to underline that Russia had inherited the USSR’s permanent seat. The then-secretary-general’s text was largely window-dressing for this diplomatic formality.

There was no comparable top-level inter-governmental event to endorse the “Brahimi report” in 2000. While there was flurry of small peacekeeping reform initiatives in 2009—stemming from a major crisis in the eastern DRC that year—these were mainly exercises for policy officials. A few foreign ministers were involved at most.

The idea of kicking peacekeeping operations up to a higher level largely lies during the second term of US President Barack Obama. Obama convened a discussion of peacekeeping with major troop contributors at the 2009 General Assembly but—perhaps because the president found some of his fellow leaders’ stem-winding speeches tedious—there was no real follow up until 2014. That year, US Vice President Joe Biden led a discussion of boosting peacekeeping forces, paving the way for a bigger pledging conference on the margins of the 2015 General Assembly led by President Obama himself.

This was a somewhat surreal event. Presidents and prime ministers had a few minutes each to offer soldiers, aircraft, and even canine units to the blue helmets. Some seemed well-informed about the issues at stake. Others just wanted to share the stage with Obama (and there was some consternation when he left half way through). But if this was political theater, it worked. As Alison Giffen notes, the 2015 session and succeeding defense ministerials in London and Vancouver generated promises of 50,000 new personnel. Thanks to the Obama process, British medics and engineers have built a hospital in South Sudan, Portuguese commandos have deployed to the Central African Republic, and Salvadorean helicopters patrol in Mali.

The A4P meeting this September takes the model of top-level engagement on peacekeeping pioneered by Obama, but shifts the focus from force generation to politics and policy issues. Secretary-General Guterres may not quite have the political pulling power of Barack Obama, but he can expect a reasonable turnout of leaders interested in peacekeeping to participate. DPKO and DFS are working closely with member states on preparing the event—a cross-regional group of ten states including Security Council members and major troop contributors have helped shepherd consultations on the summit declaration—and a good cross-section of African, Asian, European, and Latin American leaders should show up on the day.

But a few difficult questions still hang over the event. There is, for example, some concern about the participants list. Will US President Donald Trump drop by, and if he does, what will he say? US officials have been broadly supportive of A4P to date, and US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley persuaded Trump to attend an event on secretariat reform with Secretary-General Guterres last year. But after Trump’s disruptive performance at this month’s NATO summit, other leaders may worry about what he might say or do if given the chance to opine on A4P.

Equally, or even more importantly, will China lend the initiative its support or keep its distance? President Xi Jinping stole the show in 2015 by offering 8,000 new peacekeepers to new UN missions, although getting them on the ground remains a work in progress. Xi does not usually attend the General Assembly, but other leaders and diplomats will still be keen to know if China endorses A4P, especially as Beijing has recently signaled skepticism about UN missions’ work in domains such as human rights promotion. Chinese diplomats have nonetheless engaged seriously in discussions of the A4P draft declaration, and may decide that they have an interest in positioning themselves as champions of more effective peacekeeping.

Getting the September A4P event right will consume a lot of time and diplomatic energy over the next two months. But even bigger questions loom over what will happen once the participating leaders have come and gone. In formal terms, all the meeting will produce is a political declaration that does not bind either its endorsers or those that stay away. Diplomats favorable to the process have considered giving the text a formal status by welcoming it in a Security Council or General Assembly resolution before the end of the year. Russia may well query a full-scale council resolution endorsing the initiative. But there may be ways—such as an exchange of letters between Secretary-General Guterres and the president of the Security Council—to give A4P some credence. A broadly-worded General Assembly resolution acknowledging the declaration could also give it some extra weight moving forward.

The exact political meaning of A4P thus remains up for negotiations. A related problem is what, if any, mechanisms the countries that endorse A4P can engineer to encourage follow-up on the declaration. It was relatively easy to follow up on the Obama summit in 2015, as participants made quite specific pledges of forces that were fairly easy to track. By contrast, the A4P agenda embraces a number of policy issues and promises of political support that are harder to monitor and evaluate.

When a leader says that they will “commit to stronger engagement to advance political solutions to conflict and to pursue complementary political objectives and strategies,” what will that mean in practice? Is there a way for states to assess each other’s actions on A4P commitments without causing excessive diplomatic pain?

Nobody wants to create a complex or time-consuming reporting system to track A4P. The best option would be to find light-weight mechanisms that would still compel member states to focus on follow up to the September declaration. The simplest way to proceed would be for countries that endorse the A4P declaration to report voluntarily and independently on their steps to fulfill it, using platforms like Security Council thematic debates on peacekeeping. But such an ad hoc approach could lose momentum quite quickly, demanding a more structured approach. Options include:

- A Group of Friends, or “High Ambition Coalition” (similar to inter-governmental groupings created to pursue parts of the SDGs) to act as a forum for member states excited by A4P to report on follow-up and share ideas;

- The appointment of an A4P Rapporteur by those who endorse the summit declaration—a senior political figure with a mandate to assess and report on the implementation of the commitments agreed in September;

- Inviting civil society and academics to supply “shadow reporting” on progress on the A4P commitments outside inter-governmental structures;

- A field-up approach, by which UN mission leaders should engage with representatives of pro-A4P countries—such as ambassadors, development officials and, within UN missions, contingent commanders—to apply the initiatives’ principles on the ground, operationally, and diplomatically.

One potential milestone for tracking progress on A4P will come in March, when the UN will host another ministerial conference to follow up on the Obama initiative on force generation. This could also be a platform for further discussions of A4P, linking the two processes. Under any circumstances, most of the impetus for advancing on the A4P agenda will have to come from within states themselves. But quibbling about the long-term future of A4P may miss the immediate point of the exercise. At a time when the UN’s members are irredeemably divided on many security issues, Secretary-General Guterres still has a chance to pull together a posse of leaders to reaffirm that blue helmet operations matter this September. The political signal alone matters.

Richard Gowan is a Senior Fellow at the United Nations University’s Centre for Policy Research.