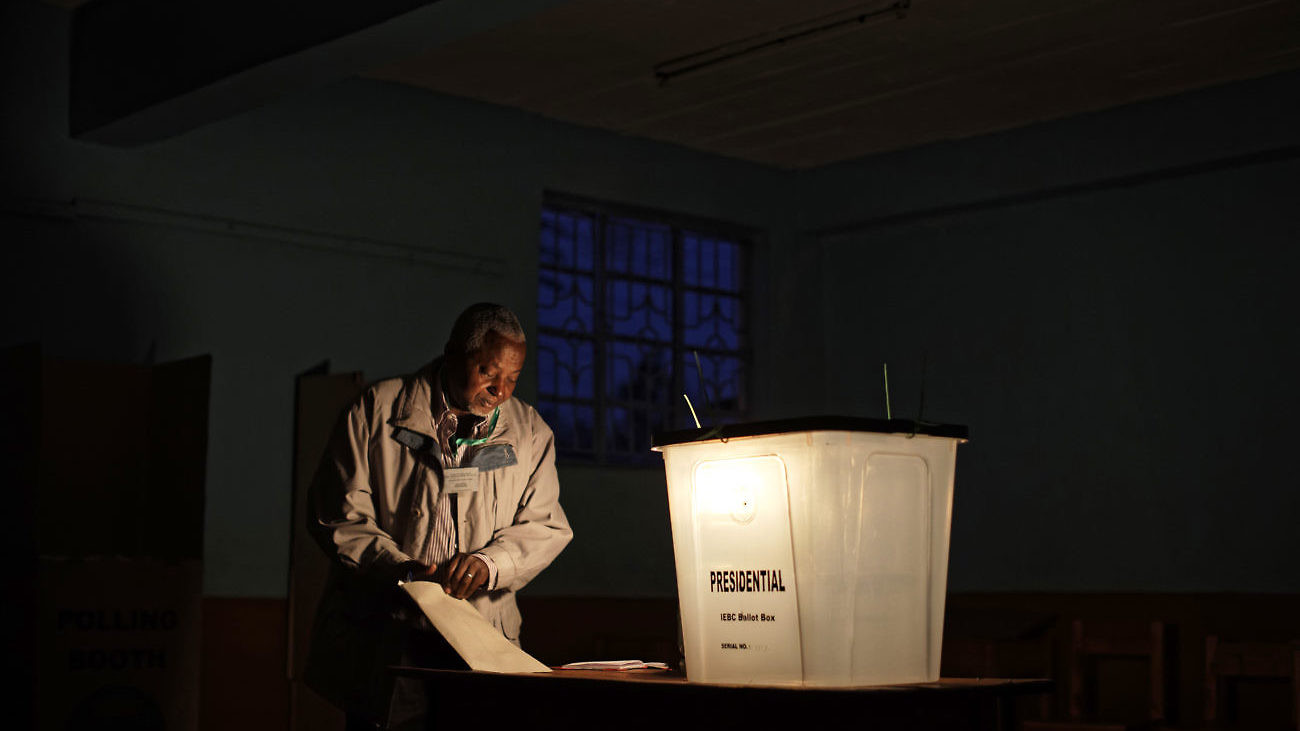

An electoral worker prepares a ballot box by gas lamp just before dawn in Gatundu, Kenya on October 26, 2017. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

The election of Uhuru Kenyatta for the second time in a span of less than three months is the culmination of an uncertain period that, for many, centered the rule of law and the integrity of the electoral process into the national political discourse. The annulment of the August 8 presidential election by the Supreme Court on the premise that it did not meet the standards of credibility brought about a violent police crackdown, intimidation of judges, political theatrics, and ever-decreasing confidence in the electoral commission, as witnessed in the October 26 election environment. Beyond the Kenyatta versus Raila Odinga framing of the election, this period has ultimately been one of intense and varied debate on the kind of democracy and peace Kenyans want.

Kenya’s general elections have historically been characterized by varying degrees of violence and tension and in this sense the October 26 election was unremarkable—including the protests by opposition supporters demanding the total reform of the electoral commission. The use of excessive and lethal force also pre-dates this election period. In a report by Amnesty International, Kenya’s security forces were implicated in the killing of at least 122 people in 2016. The use of live bullets and excessive force against protestors, bystanders, and in raids on homes is part of this trend on the part of law enforcement to use violence, even when other lawful avenues are available. As a result, an estimated 36 lives were lost during these recent elections according to the human rights group Independent Medico Legal Unit (IMLU).

In the past the demand for a peaceful election was used as a pretense to overlook electoral discrepancies despite an abundance of questions and issues with the system. The legitimacy of the October 26 repeat election thus hinged on the ability and willingness of the electoral commission to conduct the reforms needed to meet the expectations of Kenyans and the international community that the process would be free, fair, and credible. Opposition leader Odinga and his National Super Alliance (NASA) called for protests to pressure the electoral commission into enacting a list of changes they deemed crucial to a legitimate process. Odinga withdrew based on an assessment that these changes were not implemented and boycotted, claiming that it was counter-productive to engage in another flawed process. There was some speculation that Odinga calculated that he would not win the election and used the commission’s challenges as a pretext to withdraw. Whatever his motives, Odinga’s withdrawal turned the October 26 election into a race of Kenyatta against himself, despite the presence of other candidates on the ballot.

Outside of the posturing of candidates, the integrity of the election was seen by many Kenyans as a cause for concern. Days before the poll one of the commissioners, Roselyn Akombe, resigned and fled to the US where she publicly stated that the partisan electoral commission was incapable of delivering a credible poll. The commission chairman subsequently highlighted his doubts on meeting the expectations for a fair election. These events led to a further dip in public confidence. Various national and international civil society groups called for a postponement of the rerun to enable the commission to fully meet these demands. A petition was filed to halt the election but the Supreme Court did not convene the quorum needed to hear the petition.

The day of the election itself was marked by layers of challenges and institutional inconsistencies. Security issues and protests led to the cancellation of elections in four counties considered strongholds of Odinga. According to the electoral commission, the remaining forty-three counties saw a voter turnout of 38.8%—the lowest in Kenya’s history. While the boycott by opposition supporters largely contributed to the low voter turnout, many apparently did not believe that the process would be free or fair.

The relaying of contradictory voter turnout numbers by the electoral commission has strengthened skepticism over the credibility of the poll. Ultimately, Kenyatta was declared president-elect with 98% or 7.4 million of the 7.6 million valid votes cast. A collective of different groups under the umbrella “We the People” rejected the poll citing its lack of credibility and legitimacy. They called for a disbanding of the electoral commission and advocated for a one-year transition period to facilitate the healing of the country and to give time to form a new electoral body. The Elections Observation Group (ELOG) noted that the election may not have been conducted in line with the constitution and electoral laws.

The declaration of Kenyatta as president-elect has not put an end to this period of uncertainty. The Supreme Court is still to hear and rule on the different petitions that have been filed to nullify the election results. The opposition continues to protest Kenyatta’s legitimacy through a national resistance campaign that has initiated economic boycotts and plans to form a people’s assembly to restore democracy and the rule of law. With the setting-in of election fatigue and ever-increasing political uncertainty, calls for dialogue have been made by various actors. While these are welcome signs, any dialogue will need to be centered around justice. The question then becomes: how possible is such a dialogue? While it does not seem likely that another runoff will be held, nonetheless these concerns will continue to remain as challenges to democratic governance in Kenya into the future.

Sheila Kinya Gitonga is a Peace, Security and Development Fellow at the African Leadership Centre, King’s College and a 2017 African Junior Fellow at the International Peace Institute (IPI).