A polling volunteer passes ballot boxes for the upcoming Kenyan election. Nairobi, August 7, 2017 (Jerome Delay/Associated Press)

On August 8, millions of Kenyans will cast their vote in what is expected to be the country’s most competitive general elections to date. Ballots will be cast for 290 members of parliament, 47 female county representatives, 47 senators and governors, as well as the president.

The presidential vote will be a rematch of the 2013 poll that pit incumbent Uhuru Kenyatta against his ex-rival, former prime minister Raila Odinga. By any measure, this election is expected to be the closest contest to date between Kenyatta and Odinga, raising the political and economic stakes for the country.

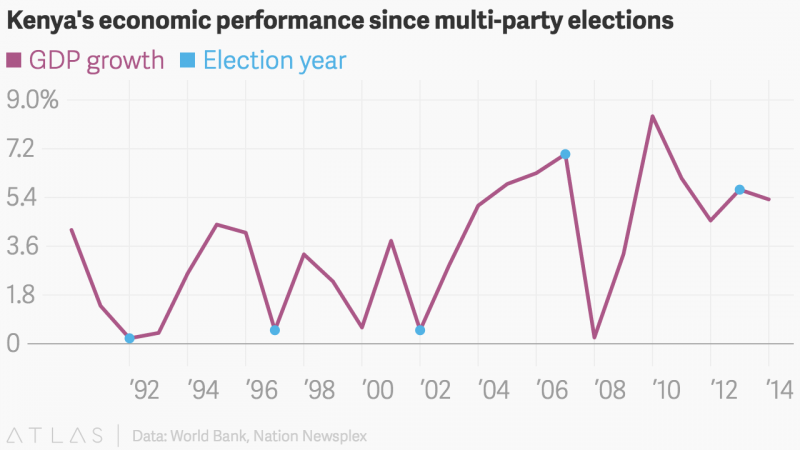

As Kenya is the undisputed economic anchor of the region, the smooth execution of the August 8 elections will be critical for wider East Africa. Kenya remains one of the largest and most vibrant economies on the continent and any sign of political and/or economic volatility will be felt well beyond its own borders. There is evidence from the past to suggest that fears of post-election instability have impacted the country’s economy.

No matter who wins, it is likely that the candidates will challenge the results of what analysts are already calling the most expensive election in Africa. Any such challenge will have the worrying effect of eroding public confidence in the Independent Election and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) and the judiciary, the two institutions responsible for safeguarding electoral integrity. Public trust in these institutions last hit a low in 2007, and the bloody aftermath of that year’s elections stands as a stark reminder of what could transpire when people lose faith in the integrity of these institutions.

In the 2013 election, when Kenya avoided a repeat of 2007-08 and held relatively peaceful elections, East Africa heaved a collective sigh of relief that reverberated throughout the continent and many other parts of the world. This was due in part to the electoral cycle: Political tension tends to rise when incumbents are defending their seats, and in 2013 incumbent president Mwai Kibaki had already served two terms and wasn’t eligible for re-election. By then public confidence in the IEBC and the judiciary had also improved compared to the previous election.

This time around, however, the odds appear once again stacked against the smooth running of the polls. Firstly, Kenyatta wants to get re-elected, so he will be seeking to use all the resources at his disposal to retain power. More critically, public confidence in the electoral commission and the judiciary is once again falling, to levels reminiscent of those in 2007. Both institutions have come under attack from both the opposition, which has been critical of the IEBC, and the government, which has directed its criticism at the courts. Some of the latter has come directly from President Kenyatta toward the judiciary. These developments have the stage for potential challenges to the election results.

Key Factors to Watch

The Electoral commission: The IEBC has been since the beginning of the year, with allegations levelled against it that include legal breaches, logistical inefficiencies, and transparency issues surrounding its procurement process. There are also concerns over the IEBC’s preparedness to conduct and execute an election day without any major glitches. Managing elections for president, governors, senators, and county representatives is a logistical challenge under normal circumstances, but given the delays in staffing senior leadership positions and procurement issues that plague the organization, the credibility and reputational stakes for the Commission have undoubtedly increased.

The high probability of close elections both at the county and presidential levels makes matters are even more complex. There is a risk that neither Odinga nor Kenyatta will secure the necessary 50% +1 of votes cast, thus triggering a second-round vote. This would be unprecedented and would be arriving at a time when political and social pressures are high, further exerting undue pressure on the IEBC.

Leaving the presidential election aside, it is also possible that certain gubernatorial and other local elections might not result in a definitive winner. Will the IEBC be able to hold it all together?

The Economy: Although ethnic divisions are typically the focal point of Kenyan elections, this year concerns about the economy are taking centre stage. Inflation is on the rise, led by food prices, reaching a peak of 21% year-on-year in April. This pushed headline inflation to a five-year high of 11.5% in April 2017, up from 10.3% in March.

The rise in food prices is primarily the result of drought in some parts of the country, which drove up the prices of staple commodities such as maize, sugar, and vegetables, and in some cases has led to shortages. Criticism of the government’s handling of the situation may, in fact, translate into a protest vote against the government at the polls.

Security: One important similarity between the 2017 and 2013 election environments is the absence of either terrorism and the militant group al-Shabaab, or the fact that Kenya remains at war in Somalia, as a campaign issue. It only took a few months after the elections in 2013 for al-Shabaab to make its presence known with the horrific events at the Westgate Shopping Centre that left 67 people dead. But terrorism and insecurity remain a constant threat in Kenya, and groups like al-Shabaab and others may look to undermine and influence the election outcome in the weeks leading up to August 8, or even in the days after.

Post-Election Environment Remains Uncertain

Assuming all goes well after the polls, whether the presidency is occupied by Kenyatta or Odinga, more problems are looming—particularly on the economic front: Kenya has mounting debts. Starting the end of this calendar year to 2019, fiscal resources are expected to come under pressure due to external debt servicing. For example, in December, a $750 million commercial loan, secured in October 2015, will be due. This will be followed by the expected repayment in June 2018 of a $600 million loan from the African Export-Import Bank, earlier secured to support cash-strapped Kenya Airways.

Furthermore, in 2019, the five-year $750 million Eurobond, issued in 2014, will fall due in December, as well as a portion of another $800 million syndicated loan granted by commercial banks, including Citigroup, Standard Bank, Standard Chartered, and Rand Merchant Bank. These payments are expected to result in external debt servicing rising by a whopping 242%, from $424 million to $1.4 billion in the 2017-18 budget. These repayments are all expected to happen against the backdrop of a weaker Kenyan shilling and a stronger US dollar, which the majority of Kenya’s external debts are denominated in. Needless to say, the new president may not have much time to bask in the glory of his victory.

Ahmed Salim is a Vice President at Teneo where he leads the East Africa political risk division. This article originally appeared on Global Voices. It has been edited slightly for style.