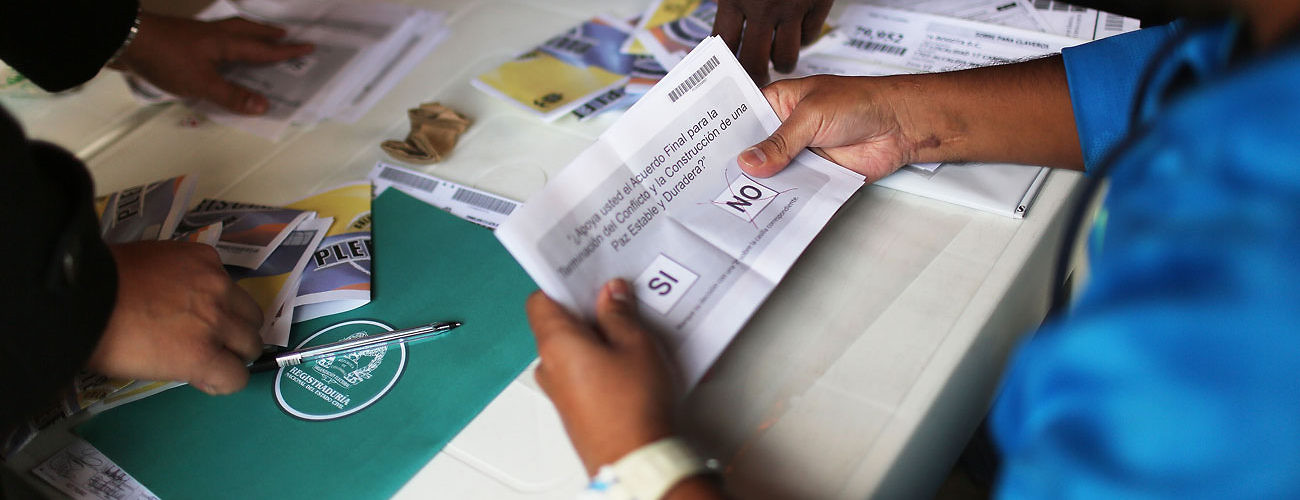

Yesterday, the people of Colombia rejected the historic peace deal between the government of Colombia and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP) in a country-wide referendum, signifying the end of the peace deal. However, this must not be the end of the peace process. It is now crucial for Colombia to learn from other experiences what can be done to save the peace process. If the relevant actors in the country can act together quickly, the “No” vote can be an opportunity for renewed negotiations to ensure ownership over the peace process by all groups in the country.

There are two options at this point. For either to succeed, it is essential that the parties remain committed to the ceasefire and the goal of peace. First, the parties can return to the negotiation table to produce a revised peace deal, which addresses the major grievances of the Colombian people. Second, a National Dialogue involving all major political and societal forces in the country, as well as the diaspora could address the weaknesses in the process to date. It is important to remember that the FARC-EP is not the only armed group in the country. An all-inclusive process could also provide an opportunity to engage the remaining armed actors, most of all the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN).

From historical experiences, we know that the support of a peace deal from the main political, economic, and social groups in the country, as well as the general public, is essential for making peace deals sustainable. Hence, even if the results of the vote had been a narrow “Yes,” there might not have been sufficient political commitment to ensure a smooth implementation process.

The peace deal was signed only a week ago in a ceremony in Cartagena attended by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon, US Secretary of State John Kerry, and many other world leaders, all of whom congratulated Colombia on its historic achievement: ending the oldest armed conflict on the continent. The Colombian peace agreement has already been referenced as a shining example for the rest of the world. For most people, therefore, a “NO” vote was unthinkable.

Yet, this is not the first time in history that a peace agreement has been rejected by the general public. In Guatemala in 1999, and in Cyprus in 2004, peace agreements, or the reforms needed to implement agreements, were defeated in referenda. What have these countries done to overcome the deadlock? In Cyprus, it took more than a decade for new peace negotiations to begin in earnest. However, in contrast to Colombia, Cyprus has a UN Peacekeeping force on the island that ensures a permanent ceasefire. Colombia does not have this luxury, as its ceasefire depends on the goodwill and commitment of the armed actors. In Guatemala, political actors attempted to implement the agreement through legislative (rather than constitutional means), albeit with limited success.

Why would populations reject a negotiated peace deal? Though every context is of course different, there are two main reasons. First, people may reject an agreement because they do not see their grievances and fears sufficiently addressed. All agreements involve compromise, and therefore have weaknesses; however, the fears and grievances of populations also need to be taken seriously. Second, ratifications may fail when peace processes become too politicized. Political parties campaign over the weaknesses in the agreement, and amplify people’s fears, in order to position themselves to benefit from the failure of the agreement. The outcome in these cases often boils down to who has the better campaign to win people’s hearts and minds, rather than the merits of the agreement per se.

What can be done to save the peace process now? From historical experiences, we know that in most cases when referendums resulted in a “No” vote, it took either many years until new negotiations could restart, as in Cyprus, or else, as in Guatemala, the process never fully recovered from the defeat of the referendum, and most of the gains from the peace deal–especially with regards to crucial issues such as land reforms or rights for indigenous groups–were never implemented. This is reflected in the extremely high rates of violence (in some years even exceeding the worst years of the conflict) seen in Guatemala since 1999.

Colombia cannot afford for this to happen. It is now up to the government, the FARC-EP, as well as the opposition parties and major societal groups in the country to quickly move forward to save the peace process. How can this be done?

First of all, it is essential that the ceasefire holds and that the parties remain committed to the peace process. Once that is established, there are two options to proceed. One is a renewed negotiations between the government and the FARC-EP to renegotiate a revised peace deal that takes the major grievances of the Colombian people against this deal into consideration, followed by another referendum. The other is that the parties could establish a National Dialogue involving all major political and societal forces in the country, as well as representatives of other armed groups, civil society organizations, and social movements in a multi-stakeholder process that is owned by all Colombians. This National Dialogue must take place in Colombia, so that this time, people can really feel ownership over the peace. It must not be a consultative forum that takes place only in the capital, but must be connected to the regions and to the Colombian diaspora. This could be achieved through a representative National Assembly, composed of delegates representing all the groups and constituencies identified above, and which remains tightly connected with a network of local dialogue initiatives spread throughout Colombia (with a particular focus on conflict-affected regions).

It is essential that all the relevant actors maintain their commitment, continue the peace process, and use the “No” vote as a window of opportunity for an all-inclusive, broad-based social and political process involving all relevant actors in the country. Only if the Colombian people’s legitimate grievances are addressed can lasting peace be brought to Colombia.

This piece was first posted on the IPTI Peace and Transition Observatory.