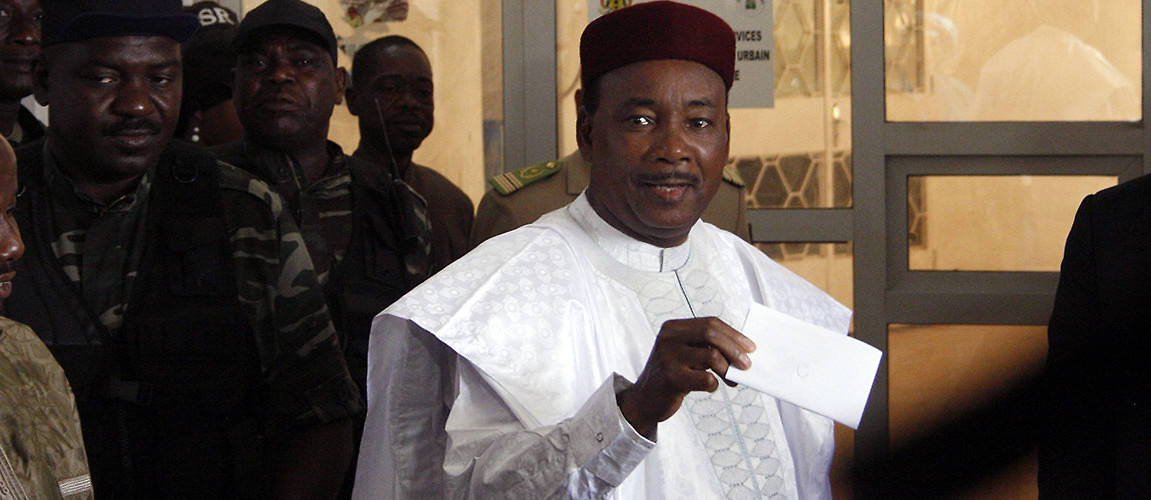

Niger incumbent President Mahamadou Issoufou, prepares to cast his ballot during runoff elections. Niamey, Niger, March 20, 2016. (Gael Cogne/AFP)

Niger held the second round of its presidential elections on March 20th. Amid a partial opposition boycott and the medical and legal difficulties facing his main challenger, incumbent President Mahamadou Issoufou won a sweeping victory. Issoufou will begin his second term in a climate suffused with worries about security throughout West Africa. It is a climate that could reinforce his international image as a key player in regional stabilization efforts. At the same time, the mechanisms of his victory included significant repression of dissent, raising questions about whether Niger’s domestic political space will contract further in the five years to come.

With recent attacks on upscale hotels in Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Mali—including a fresh attack on March 22nd—and with ongoing violence in the Lake Chad Basin associated with Nigeria’s Boko Haram movement, Issoufou can expect regional security to be a major theme during his second term. This will mark substantial continuity with the recent past. As I have written previously in the Global Observatory and elsewhere, Issoufou’s firm term was marked by securitization—his administration’s focus on combating al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Boko Haram, while preventing any domestic rebellions—and by a partial closure of political space, involving arrests of opposition leaders and civil society activists.

Analyst Tommy Miles has argued that “by 2013, the wheels had come off” Issoufou’s promised program of domestic development and prosperity for Niger. The president embraced the “War on Terror,” Miles explains, in part because of these domestic setbacks. Whatever the cause, security is a major element of Issoufou’s platform; after casting his own vote on March 20th, he said, “A single term in office is not enough to overcome all the challenges, in particular I am thinking of the security challenges.”

If 2013 marked the beginning of intensive securitization in Niger, that was also the date when Issoufou’s winning electoral coalition from 2011 fragmented, most notably when the Speaker of the National Assembly, Hama Amadou, moved into the opposition. From August 2013 to the present, the political climate has been tense in Niger; this is symbolized by Amadou’s exile from Niger from 2014-2015, and his imprisonment from 2015-2016, even as he emerged to become Issoufou’s main challenger in this year’s elections.

During this electoral campaign, Issoufou has not engaged in the kind of blatant vote rigging that some of his West African peers have attempted. If he had, one would not have expected him to fall short of the 50% mark in the first round, which took place on February 21st. Such a result would have allowed him to win outright; his tally of 48% triggered a runoff with Amadou, who had placed second with nearly 18%. Yet Issoufou used law enforcement to tremendously constrain Amadou’s campaign, holding the former speaker in a remote prison and arresting other politicians as well as prominent opposition voices from wider society, such as the singer Hamsou Garba. The second-round voting occurred amid a heavy security deployment and restrictions on political assembly in the capital Niamey.

In the end, Amadou was not even present in Niger on the day of second-round voting; on March 16th, he was evacuated to France for medical treatment, leading to considerable speculation that his imprisonment had left him greatly weakened. Matters were further complicated by a partial opposition boycott of the second round. An opposition coalition, COPA 2016, announced the boycott in early March, but Amadou’s name remained on the ballot and he did not officially withdraw.

Suppression of the opposition and the boycott confusion helped Issoufou to achieve a decisive second-round victory: nearly 93% voted for him, and around 7% for Amadou, though Amadou may gain a bit as further results are released. According to official preliminary results, turnout fell somewhat, from nearly 67% in the first round to just over 60% in the second, and the official estimate of the overall second round turnout rate has been reported as 56%. Yet lower turnout alone may not explain the outcome: if the official results are credible, this means that Issoufou may have not only courted the non-Amadou opposition, but also attracted some of Amadou’s own supporters. COPA 2016 has rejected the second round as a “sham,” but if Issoufou’s high numbers hold in the final results, he will likely claim a sweeping mandate for continuity.

This victory does not, however, position Issoufou to become an absolutist ruler in Niger; there are historical limits to what the country’s political system will tolerate. Issoufou began his first term in 2011 after winning an election organized by a short-lived, caretaker military regime. That regime came to power in 2010 after the previous civilian president, Mamadou Tandja, rammed through a constitutional referendum that gave him a third, extra-constitutional term in office. Tandja’s experience may lead Issoufou to never even consider raising the issue of a third term for himself.

Looking ahead, Issoufou’s immediate concerns center on security, both in terms of restoring full control over the southeastern Diffa Region, which has been badly affected by Boko Haram, and by preventing attacks elsewhere, especially in the capital. The spate of hotel attacks in West Africa has governments, expatriates, and major businesses spooked, and Issoufou will be at pains to ensure that Niamey does not become the next site of a hotel assault. The emphasis on prevention will likely lead Issoufou to continue pressuring the international community to escalate its military interventions in Libya, Niger’s least stable neighbor.

How this atmosphere will affect the political space at home is an open question. In May 2015, Nigerien security forces detained human rights activists who had criticized the government’s handling of security and humanitarian issues amid the anti-Boko Haram campaign in Diffa. On the one hand, with the elections now past, Issoufou could be more tolerant of criticism; on the other hand, security measures may become increasingly forceful, including against civilians. The administration may decide that it wants to avoid international embarrassment and muffle the few domestic activists who have the access and platforms to document and publicize controversial developments in remote regions. If there are further detentions of human rights activists, it will be one sign that securitization in Niger is still coming with a significant price.