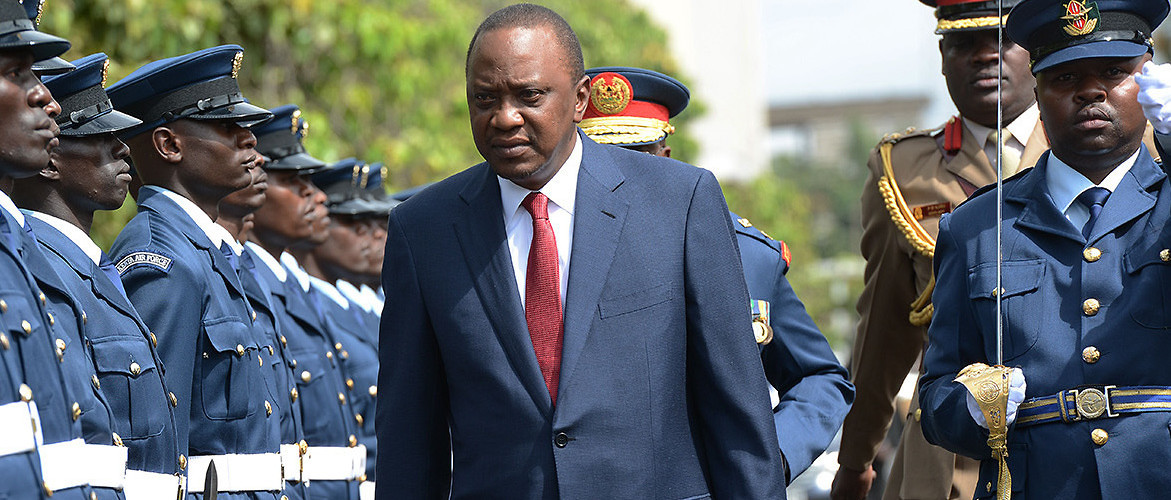

Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta prepares to address the country's parliament. Nairobi, Kenya, March 26, 2015. (Simon Maina/AFP/Getty Images)

United States President Barack Obama’s July visit to his father’s ancestral home elicited a lot of hope for a country working to maintain its reputation as an island of peace in a region of turmoil. As Obama noted, Kenya has made tremendous progress economically and in the political realm; its economy is growing very fast, and its democratization process is on the right track. Kenya has one of the strongest constitutions in the region, promulgated in 2010, in which popular sovereignty, structures and powers of government, civil society, and a bill of rights are well defined.

However, the current government has made several attempts to reverse the many democratic gains that ordinary Kenyans have made to secure their rights within the 2010 constitution, under the pretext of fighting violent extremism and terrorism. Obama’s spotlight on Kenya therefore offers a tremendous opportunity to tackle the security challenges without compromising the freedom of its people.

President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government faces many challenges, including corruption, non-inclusive employment within the public sector, and the need to provide security and development (including empowerment of women). His government is accused of awarding public sector jobs to business associates and to the Kikuyu and the Nandis—the ethnic groups of the president and deputy president respectively—to the exclusion of the rest of Kenya’s 41 ethnicities. As a result, development is also skewed to favor these groups of the president and his deputy. It’s worth noting that the democratic space in Kenya has opened up since 1992; however, the presidency has only rotated between those two major ethnic groups in that time.

Kenya’s 2010 constitution was poised to curb the non-inclusive regional development pattern, but it is not receiving enough tangible support from the central government, which retains the larger share of the national revenue. To make matters worse, the devolved county governments are constantly quarreling over power and stand accused of corruption.

Meanwhile, the Somalia-based Islamist insurgency al-Shabaab seems to have exploited Kenya’s vulnerabilities. The terror attacks on Kenya’s affluent Westgate mall in Nairobi; in Mpeketoni, and Lamu; and at Garissa University; along with incidents of violent extremism in Mombasa, have shaken Kenya’s tourism industry. The government’s response to these attacks has been to randomly arrest Kenyan-Somalis, and the historical marginalization of northeastern region of Kenya has made security issues in the country more complex. Many fear that this marginalization may push more people into radicalization.

Kenya is facing further challenges related to female genital mutilation (FGM) and civil rights. FGM is a tradition that is still practiced by some ethnic groups in Kenya and is part of a culture that denies young girls access to education. Violence against women of all ages is also a major problem, as is denial of gay rights, which has been dismissed outright by Kenya’s president as a “non-issue.” There has, furthermore, been a lack of gender sensitivity in the amnesty offered to violent extremists by the Kenyan government, even though the issues that affect men and women in radicalization are quite different.

How can Kenya choose the path toward a bright future? The leadership must pursue inclusive policies of national identity and development policies. It must disavow ethnic preference and slander and curb rampant corruption in the public sector. It must streamline the governance structures, uphold transparency and accountable, and respect the rule of law.

Kenya’s reputation of an island of peace came in the 1980s and early 1990s, though it had its own internal political problems back then. Little by little, Kenya has become stronger with each passing year. Let’s hope it continues on that path.

Moses Onyango is Director of the Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the United States International University—Africa, and a Fellow of the African Leadership Centre.